Film: The Man Who Knew Infinity

At heart, this is a movie about Maths, with arguments about how best to do it

Differences between Cambridge and 'The Other Place' can often be overstated: yes, we’re prettier and better at science and History (and do better in the rankings), but they’re not so bad either. In cinematographic portrayals, though, there seems to be a subtle trend emerging. When Oxford appears in film and on TV, it is often as a portrayal of place and time and people more-or-less just being and interacting with one another – and often being very drunk. (Think Brideshead, Shadowlands, or The Riot Club. True Blue is the exception.)

Movies set in Cambridge seem instead to be about people doing things other than falling in love and getting drunk. Think here of the running scenes in Chariots of Fire, the intriguing in Cambridge Spies, or the cosmology that gripped Professor Hawking amidst everything else in The Theory of Everything. To this tradition of films which focus on people who do rather than merely are at Cambridge, we can now add The Man Who Knew Infinity.

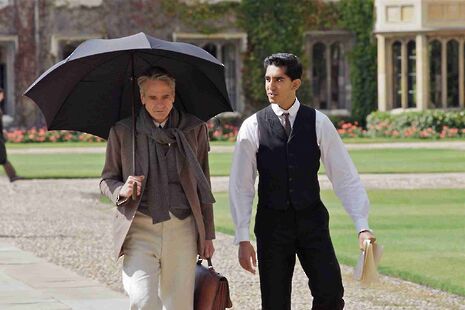

The film tells the obscure story of Srinivasa Ramanujan (played by Dev Patel), the poor mathematical genius from Madras who claimed to receive mathematical revelations on his tongue from the goddess he worshipped when he slept or prayed. He wrote to the Trinity fellow GH Hardy (Jeremy Irons), who brought him to Cambridge on the cusp of the First World War. The Hardy-Ramanujan collaboration (with assistance from John Littlewood, played by Toby Jones) led to significant breakthroughs in pure Maths and number theory. Ramanujan went from being someone without a degree to a Fellow of the Royal Society and – even more remarkably, the film suggests – of Trinity College, Cambridge. These achievements are astounding when we consider the fact that Ramanujan died at 32 of tuberculosis.

As other reviewers note, the movie’s treatment of the collaboration and Ramanujan’s time at Cambridge is not remarkable. The real conflict in the story is about mathematical method. Ramanujan wants to show only conclusions, while Hardy insists on rigour. Without proofs, Irons’s character tells him, people will not take him seriously. This is not the stuff of high drama. The racial prejudice which Ramanujan faced and the romantic subplot involving his separation from his wife (Devika Bhise) and his conniving mother (Arundhati Nag) might have been more engaging if given more time, but I applaud screenwriter/director Matthew Brown’s choice to resist easy sensationalism. At heart, this is a movie about Maths, with arguments about how best to do it. So much academic work – especially in a theoretical area like pure Mathematics – takes place in our heads. It is hard to make a truly gripping movie about such a subject matter.

The film has many redemptive aspects. The performances are almost all wonderful: Irons, Patel, and Jones all play their characters as at least this Ramanujan-aficionado always imagined them to be, with lines and incidents faithfully drawn from real life. Jeremy Northam, as Bertrand Russell, steals virtually every scene he’s in, much as I envision the real Russell would have. (Sadly Wittgenstein, also at Cambridge at the time, doesn’t feature.)

The film is also a fetching depiction of Trinity during a time of internal and external tumult (complete with a Stephen Fry cameo to tell us that it’s where the greats went). Most scenes take place on Trinity’s Great Court and Nevile’s Court, with nods to Newton, Byron, and the Wren Library. There is even a little foreshadowing of Trinity’s (much) later progressiveness: one of Ramanujan’s "kind" (an Indian) would never inhabit the walls of the Great Hall, a fellow says, staring almost precisely at the spot where Amartya Sen’s portrait now sits. Were there any risk that Trinity was not sufficiently sure of its place in the world already, this film should help to quell any lingering insecurities.

On balance, The Man Who Knew Infinity is probably more a film to watch with a cup of cocoa at home one autumn or winter afternoon than one that demands a trip to the cinema before finals, which is a pity. There were other angles that could have been taken with the story. David Leavitt’s 2007 novel The Indian Clerk suggests that Hardy was a fascinating character in his own right, but his sexuality and secrets are not really explored. This is understandable: Ramanujan’s folk hero status in India is starting to draw audiences to the film there, and perhaps these aspects would have played less well among traditionally more conservative Indian film-going audiences.

Stories of Hardy and Russell and Wittgenstein – and maybe even people who were at other Cambridge colleges during the First World War – will have to wait for other films for now. In the meantime, there is still much for votaries of the Cambridge religion to love in The Man Who Knew Infinity.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026

News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026 Theatre / Camdram publicity needs aquickcamfab11 January 2026

Theatre / Camdram publicity needs aquickcamfab11 January 2026 News / Cambridge academic condemns US operation against Maduro as ‘clearly internationally unlawful’10 January 2026

News / Cambridge academic condemns US operation against Maduro as ‘clearly internationally unlawful’10 January 2026 News / SU stops offering student discounts8 January 2026

News / SU stops offering student discounts8 January 2026