Sentenced to Vote

Lock ‘em up and throw away the key to prisoner rehabilitation

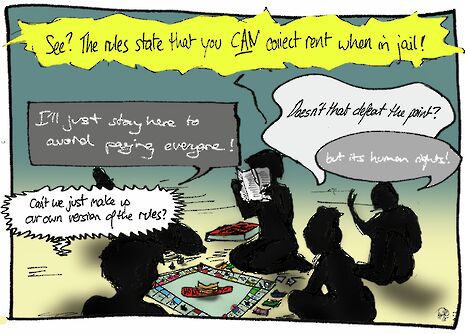

‘It makes me physically ill even to contemplate having to give the vote to anyone who is in prison’. Such were the words of David Cameron in backing the decision of the House of Commons to oppose prisoners’ rights to democratic participation. This development sets the Government at odds with a 2005 Strasbourg ruling that declares the current UK blanket ban on convict voting incompatible with Article 3 of Protocol 1. The ensuing constitutional implications are undeniably going to be difficult to stomach, but in terms public policy, is the potential enfranchisement of the prison population really so nauseating?

Art 3 of Protocol 1 confers the right to ‘the free expression of the opinion of the people in the choice of the legislature’. This right may be qualified by government measures if they pursue a legitimate aim and do so in a way that strikes a proportionate balance between the right and competing public policy considerations. The Grand Chamber allowed that the relevant domestic law pursues a legitimate aim but asserted that its application is disproportionate.

The judgment points to the arbitrariness of the ban in the form MPs seek to maintain as failing to accord Article 3 appropriate weight. It objects to prisoners whose crimes are of different gravity being alike deprived of the right and also to the fact that some prisoners under custodial sentence could have received a community penalty for the same offence and retained the right to vote under the latter. The rationale underlying the disenfranchisement of ‘anyone who is in prison’ already starts to fall apart. The decision does not compel the UK to allow all prisoners to vote but makes it incredibly difficult to justify continued imposition of a blanket ban.

However, in a sense broader that that conferred by the legal phrase, does disenfranchisement of prisoners really pursue a ‘legitimate aim’? The first policy consideration advanced to the European Court by the previous government was that the measure pursues the aim of preventing crime by sanctioning civic responsibility and respect for the rule of law. This is rooted in the idea, predominant since the early 1970s, that punishment of crime is a communication between society and offender. The imposition of a deserved sanction allows society to demonstrate to an offender the gravity of his/her offence and the offender can choose to respond to the censure of society by striving to respect the rule of law thereafter.

The communication embodied in disenfranchisement is that society wishes to exclude prisoners from participation in its life. Research demonstrates the importance of community support in preventing recidivism amongst released offenders. If a released prisoner has no links in the community, no home, no job, and no support for drug and alcohol problems (s)he is more likely to revert to crime. Reinforcing a sense of being outside the local community by disallowing participation in election of the local representative surely does not incentivise offenders to participate in the order of civic responsibility upon release. It also communicates a mentality of exclusion to the general public, further weakening community support. This can only have a detrimental impact on crime rates and the aim is no longer so legitimate in light of its impotence.

The second policy consideration forwarded as a ‘legitimate aim’ of disenfranchisement is to confer extra punishment. The notion of communication is important in an ethical sense as well as having a potential impact on crime prevention. Ghandi once said that the state of a nation’s prisons is reflective of the state of its society. Disallowing prisoners the vote represents and fosters an ethos of exclusion, apposite to social cohesion.

The prison population is relatively small and during the recent debate, ex-prisoners have told reporters that they are apathetic and may not have voted whilst in prison even if they had the opportunity. Despite this, the message of exclusion conveyed by denial of the vote has practical and ethical consequences. ‘Tough on crime, tough on the causes of crime’ has long been the rhetoric of the criminal justice system. The former part, retributive in its end, has been well tackled by successive governments. The latter part, with a holistic goal, recognising the need for investment in better social support for those affected by poverty, family breakdown, cognitive deficit and other proven causal factors, has received less systematic attention.

An accepted mentality of placing prisoners outside society makes marginalisation of their interests more easily digestible. This is unjust. Democratic participation is fundamental to the rule of law and when it is eroded without solid justification the result is injustice. It is for this reason that the attitude of the House of Commons is so unpalatable. Let us hope that David Cameron does not end up having to confer the right to vote on prisoners: we would not want him to be physically ill in such close proximity to suffering a severe bout of verbal diarrhoea.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026

News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026

News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026