A Day with Daniel Zeichner MP

Joe Robinson reflects on a bittersweet election victory with Cambridge’s new Labour MP

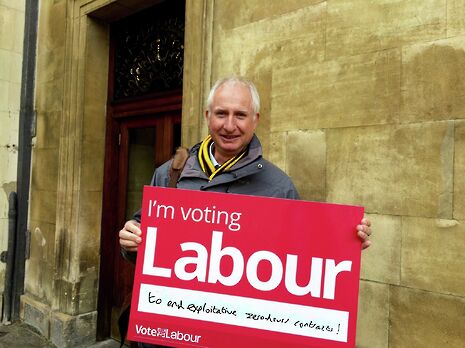

Daniel Zeichner MP may not look like a marathon runner, but as he crossed the finish line on the morning of 8th May one could be forgiven for noting a certain athletic relief among the celebrations.

The 58-year-old, who was a middle-distance runner in his youth, has proved his political stamina in 36 years in the Labour Party. 2015 was his fifth attempt to enter Parliament, having come a close third in the 2010 election and only narrowly secured reselection for the Cambridge constituency.

Despite polls indicating a strong hold for the incumbent, Julian Huppert was narrowly defeated by Zeichner. The new MP’s 599-vote majority is now the 18th narrowest in the country, amid a sea of Conservative victories across England in the most crushing defeat for Labour in decades.

As local and student activists sang the Red Flag outside the Guildhall on that fateful night, Zeichner was faced with the prospect of a House of Commons where not only would the Conservatives have their first majority in 23 years, but that David Cameron’s majority was so slim as to require his reliance on rambunctious and often unruly Tory backbenchers – just as John Major did before him.

Reflecting on that evening as I talked to him in the House of Commons, Zeichner has mixed emotions. “It was obviously terrifically exciting, and quite tense, for quite a lot of the night,” he says, adding that it was a “wonderful moment for me and for the Labour Party in Cambridge”. He is quick to praise the work of Cambridge Universities Labour Club (CULC), credited in many quarters as having played a crucial role in Zeichner’s narrow victory.

“I think the input from student campaigners was particularly significant,” he says. It seems that any pride at defying the political odds in Cambridge is tarnished by national disappointment; though “delighted that people supported us”, he calls the national result “very disappointing”.

Labour gained overall English votes compared to 2010, but Labour still lost seats, while its vote and seat share collapsed in Scotland. Current polls and research suggest that, without a significant recovery in Scotland, Labour needs a swing in excess of that which it received in 1997 if it is to win an outright majority in 2020.

Zeichner’s response to the national result, like many Labour figures, was one of shock and disbelief. The result in the East of England, which included a number of Labour-Tory marginals the party was forecast to win, “wasn’t what we were expecting, it wasn’t what we were hearing”, and tells me he has lined up meetings with colleagues over the weekend to talk about the party’s failure to live up to expectations.

Having previously worked as a political officer for the trade union UNISON, Zeichner was ambivalent about the atmosphere and culture of the Palace of Westminster. He described the swearing-in process as a “very odd thing”, and said that the initial experience of Westminster “can be a bit overwhelming in some ways”.

While he was quick to acknowledge that “the wider world loves it”, Zeichner characterised the atmosphere of the House of Commons as one which could isolate new MPs; in this respect, he mirrors his predecessor, who complained of endemic bullying in the Commons.

“My own feeling is that it can distract you from the core business that you should be here for, which is representing people and trying to do something about the challenges facing people’s lives.”

On analysing the causes of Labour’s defeat, Zeichner warned against reaching conclusions too quickly, arguing that it is “too early to come up with clear answers”. He claims there is a “danger in assuming that just because Labour didn’t win, that Labour’s analysis of what’s wrong with the country is therefore somehow invalid.”

But he defends Labour’s overall approach. “Our analysis about a low-wage, low-productivity, too-big-a-gap-between-the-top-and-bottom world is right”, arguing that “we had the some of the right answers” in terms of Labour’s policy offering.

Instead of laying much of the blame at the feet of policy, he pinpoints Labour’s failure to connect with voters and win their trust: “We really need to go back particularly to some parts of the electorate and work hard to persuade them that they can trust us, because clearly they didn’t.”

Weighing in on the upcoming Labour leadership election, he quips that the most important quality of the next Labour leader is to “be popular”, but says he does not blame the widely mocked performance of the former leader Ed Miliband for Labour’s loss in May.

Instead, he praises the Labour leader’s performance during the campaign. “He came on very well during the election,” asserts Zeichner.

Reserved for Zeichner’s ire is the press. Attacks on the Labour leader varied: for some stories, Miliband was a ruthless, fratricidal egomaniac with a string of celebrity lovers; in others, he was a bumbling, stumbling, mumbling incompetent. Like Neil Kinnock and Gordon Brown before him, says Zeichner, Miliband was “subjected to a huge and unwarranted attack, particularly from parts of the print media” despite – or perhaps because of – his stronger, more confident performance in the final few weeks of the campaign.

He concluded that because Labour leaders are “always going to get that”, it would be necessary for Labour to pick “somebody who is even more bulletproof” as its next leader.

On the current contenders, who include Andy Burnham, Yvette Cooper, Liz Kendall and latecomer Jeremy Corbyn, Zeichner said: “All the leadership candidates have got differing qualities, and the campaign over the next few weeks and months, I think, will probably reveal who’s best placed to take it on.”

Despite calls from some leftist students for Zeichner to nominate Corbyn, he backed Shadow Home Secretary Yvette Cooper, the MP for Normanton, Pontefract and Castleford and wife of the former shadow Chancellor Ed Balls.

No favourite has yet emerged in the contest, which is to be held under the new leadership election rules championed by the departed Ed Miliband. Despite owing his election to union votes, his dilution of their electoral influence is perhaps his most important legacy as Labour leader.

So far, Labour’s icy relationship with business, its neglect of so-called ‘aspirational’ voters and its utter failure to convince on issues of economic competence and immigration have presented the main debate.

Yet the next five years will be a marathon, not a sprint. If Labour is to hold Cambridge at the next election, maintain its council control and finally achieve a majority again, Zeichner will need to bring that endurance and commitment to bear once more.

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025

Comment / The ‘class’ of Cambridge24 December 2025 News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025

Comment / League tables do more harm than good26 December 2025 News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025