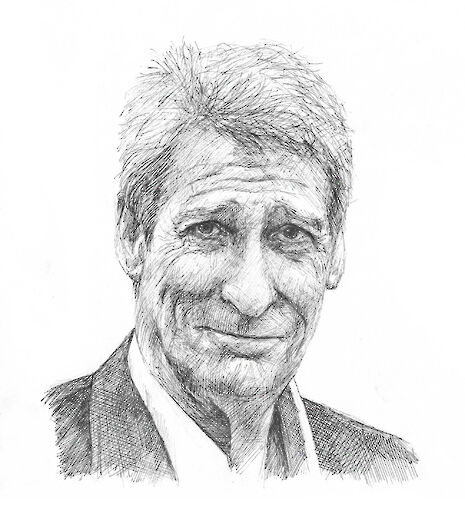

Interview: Jeremy Paxman

Following his grilling of the party leaders, Elissa Foord talks politics and politicians with this former Varsity Editor

"Pull yourself together!” No equivocation, no sugar-coating, no nonsense: even from the interviewee’s side of the Dictaphone, Jeremy Paxman takes no prisoners. And, as I found out from this reproof, no Americanisms either.

To be the object of his, albeit light-hearted, berating places me in noteworthy, if not consistently good, company: over the years the public have watched him sink his teeth into the world’s Blairs, Berlusconis, Camerons, Milibands and Russell Brands, to name only a few from a long and distinguished list. Reflecting on his portfolio of scalps, he remarks, “I don’t think there’s anything special about me really. Such notoriety or reputation as I have is more down to how I interpret my job.”

“I think a journalist’s job is to ask questions, and, if you ask questions, you should get an answer... or it should be abundantly clear that the question is not being answered.” A squirming Michael Howard being asked by Paxman 12 times in a row, “did you threaten to overrule him?” comes to mind.

“You must get a bloody answer!” he recapitulates. “The only difference between a journalist and everyone else is one of opportunity. If you have that opportunity, you owe it to your viewers to get an answer.”

A career spent cutting through political obfuscation has left him somewhat war-weary, “You see ‘em come and you see ‘em go. You see one tendentious position after another being advanced, it does tend to make you slightly jaundiced.” Yet his determination not to be “fobbed off” has in no way been assuaged, even with Newsnight behind him. The Prime Minister himself discovered this all too plainly over Easter, as 2.6 million viewers watched Cameron writhe whilst Paxman pressed him on his figures, demanding “do you know and are not telling us, or do you not know?”

His relationship with politics and politicians is complex. However, one unambiguous commitment he maintains is the importance of voting: “I think that if you live in society, you vote. If you don’t bother to vote, then you disqualify yourself from ever passing comment on anything that’s happening or being done by government… I think it really, really matters.” He admits that he did once abstain from a General Election but “felt bad about it immediately.” And once you reach the ballot box? At this, he seems faintly despairing: “I can understand that the choice is not attractive. Very often it seems like the choice between a flea and a louse.”

Despite taking Russell Brand to task for not voting, Paxman does in some way engage with his message of political disillusion. As he discusses what is at the front of his mind in the run-up to the election, he notes “there really ought to be a box on the ballot paper that reads ‘none of the above.’” He continues, “If voting were to be made compulsory, I wouldn’t really have a problem with it, but I do think that we ought to be given that opportunity.” In recent weeks, he has engaged with the leaders of the two biggest parties on the weightiest issues concerning the electorate; yet his primary concern is to have the choice to cast a vote for none of them.

Turning to the quality of political discourse at election time, he remarks, “The idiotic thing about our system is that these people stand up there and they reduce everything to simple binary choices. It’s ‘vote for me, I’m right; my opponent is wrong.’ We all know that life is much more complicated than that.”

Paxman is forthright in his belief that people should vote, but guarded as to his own allegiances. The most he will reveal on this topic is that “on the whole, I’m in favour of the government getting out of people’s lives.” A number of papers reported last year that he declared himself a one-nation Tory, although he has shied from confirming as much.

He has also been asked by the Tories to stand as an MP, and as Mayor of London, a job he would not take for “all the éclairs in Paris.” But, a member of CULC in his Cambridge days, he hails from roots further left. Wherever his beliefs do lie, he is firm that his job should be no platform for them, “You must respect the fact that you shouldn’t use or abuse your position in order to reflect your, in my case, probably pretty incoherent views on the public.”

And what of politicians themselves? In his book, The Political Animal, which discusses the anatomy of the politician, he presents them as a breed apart, to be analysed and understood with difficulty. He has frequently been accused of being ‘sneering’ towards them. However, he is quick to stress “It’s not true that they’re all charlatans. There are many noble figures who go into politics.” He continues: “The difficulty is that many of these noble people do not tend to advance as far, perhaps, as they ought to in politics. And I am sorry about that… Of course there are some scoundrels – there are some scoundrels, doubtless, even on the staff of Varsity now – there are scoundrels everywhere, and there are noble people everywhere. That is the human condition.”

He has been often charged with taking the Rottweiler treatment too far, or of spreading an irresponsible disdain for Westminster. And it is right to keep an eye on his behaviour given his political sway, but he does seem to have a healthy conception of his responsibilities. He aims to subject his interviewees all, indiscriminately, to the highest level of scrutiny he can muster. If he can do so fairly, the democratic eyebrow can be lowered.

True, power in our society does not lie in the hands of elected officials alone. And, rightly, his critics stress that he should not temper his acrimony in dealing with those whose power lies outside the realms of the constitutional, the chief executives and bank-chairmen that he encounters. But, so far as his political journalism goes, politics is a blood sport: no surprise, then, that to get results he must go straight for the jugular.

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025 Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025

Comment / What happened to men at Cambridge?31 December 2025 News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025

News / Varsity’s biggest stories of 202531 December 2025 Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026

Features / “It’s a momentary expression of rage”: reforming democracy from Cambridge4 January 2026