Too much baggage?

With some colleges offering students up to £40,000 for travel, Sarah Sheard explores whether centralising travel bursaries could level the playing field

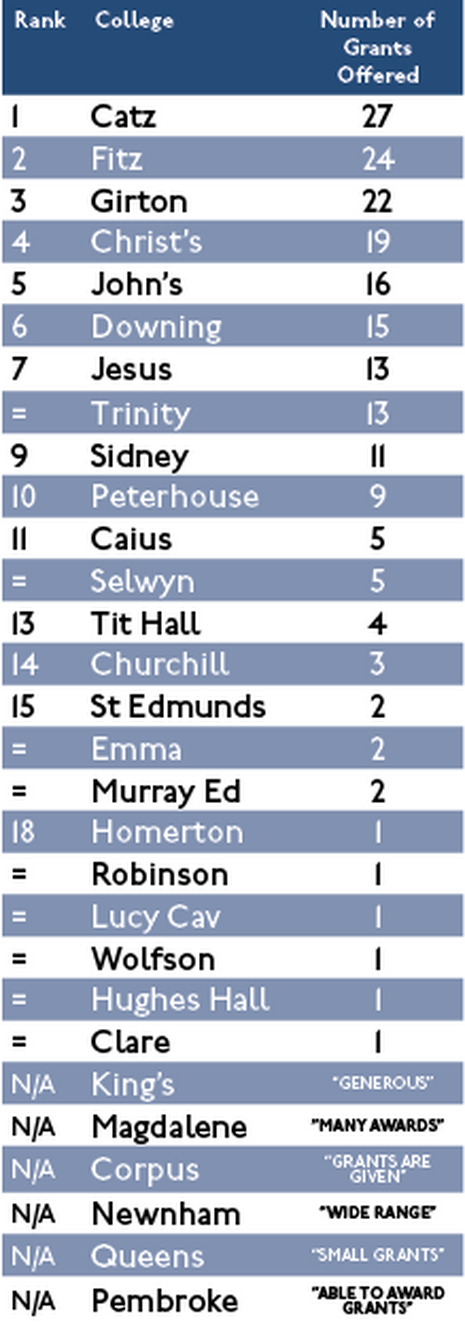

Some colleges offer up to 27 separate grants to fund undergraduates’ academic or recreational travel, a Varsity study can reveal, while others are only able to provide one or two.

Undergraduates looking for financial support while planning academic or recreational travel can look to 6 university-wide grants. While some of these funds are awarded only for academic travel, such as the A.J. Pressland fund to support language study for science students, others, like the Oxbridge-wide Gladstone Memorial Trust Travel Award, are intended for undergraduates to “travel abroad and extend their knowledge of foreign countries”. Academic-related travel is automatically ineligible for the Gladstone award.

Competition for university-wide grants for recreational travel, however, is fierce; all Oxbridge undergraduates (except finalists) are eligible for the Gladstone Memorial Trust Awards, for instance. There is thus a startling disparity in the support available to students who wish to travel for a non-academic reason – a disparity based entirely on which college they attend, and how much money they are able to offer to travelling students.

Of the 29 undergraduate colleges examined, St Catharine’s had the highest number of separate travel grants offered to students, claiming that it provides £40,000 to its undergraduates “for travel and other related activities”. Of these funds, 15 are subject-specific, and the remainder are simply “general”, although academic projects, altruistic plans and “personal travel with the aim of cultural enrichment” are apparently prioritised. The extent of travel grants at St Catharine’s, by its own admission, is the result of the generosity “given by various private benefactors over the years”.

This seems consistent with the expected pattern that older and more prestigious colleges are more capable of funding student travel, though there are exceptions; Fitzwilliam offers 24 separate grants, Christ’s 19, St John’s 16, and Downing 15. Trinity provides 7 separate funds as well as 6 fully-funded scholarship years for students spending a year at university in Paris, Germany and the US.

Clare College is unique in allocating every undergraduate registered on a course of at least 3 years’ duration the sum of £300, which may be used for “travel that either relates to that student’s course of study, or which might be regarded as generally beneficial to them”.

In contrast, more modern colleges offer much sparser opportunities for college-funded travel; Robinson lists just one travel award under its prize list, whilst Homerton similarly only has one travel grant. Mature colleges, in particular, seem to have funds that are lower than most and are restricted only to academic or conference-based travel. Hughes Hall claims it has a “small fund” to help students attend conferences as part of research. Similarly, Wolfson only offers support “to help with travel costs for students who are giving a paper at an academic conference”, a grant to which students may only apply once a year.

It should be emphasised that academic travel is mainly funded through the faculties of the university and not through colleges, and is thus not the main focus of this analysis; while some awards are focused on academic travel, the majority are for “general” trips which could more accurately be classified as “recreational”.

Comparing the number of grants that colleges award is the best way to compare the colleges. Even though the number of specific grants does not directly correlate with how much money a college allocates to its students for travel, annual variation under this method is likely to be extensive. One year’s figures are thus less representative than the number of grants.

The fact that older, more well-known colleges have more money (and potentially wealthier alumni to donate to them) is not a surprising result by any standards.

Central colleges have had a longer period to amass donations from far more alumni than newer colleges, such as Homerton, which only became a full college of the university in 2010.

St Catharine’s 2nd year Adam Butterworth, however, claims that most scholarships at his college “aren’t even taken up”. He benefited from the college’s travel funds to participate in an exchange with a university in Heidelberg, Germany during the Long Vacation in 2014.

“My tutor’s always telling me about how I should look at the bursaries page because most people don’t even know it exists,” he said.

Some grants are almost ridiculous in their specificity and obscurity, such as the Sir William Wade Award at Gonville and Caius, which is intended to support “travel in mountains”. Similarly, the Jopie Kempton Fund at Christ’s is specified as funding only “travel related to the Netherlands or associated territories, with preference for those studying Physics”, while the Medical Mission Fund at Selwyn supports only “religious (Christian) related trips… for the activities which can be regarded as missionary and medical in nature”.

One can easily imagine that such niche funds are not regularly taken up by students, especially if they are only open to undergraduates at one college, rather than the entire university.

Hanna Stephens, a 2nd year Geographer at Homerton, described it as “unfair” that a student’s college, rather than their economic status, determines whether they receive travel funding.

“I think people who have had less travel experiences and have lower household income should maybe be prioritised,” she argues.

One possible solution would be a more centralised system for travel grants that could operate throughout the university. Colleges would have the amount of money they can distribute for travel capped, with any excess or unused grants placed into a central pool to which all Cambridge undergraduates could apply. A similar scheme operates at the University of York, which, despite being collegiate, has brought all its grants together in a centralised system.

Colleges with more (and greater) donations from alumni could have slightly higher caps, to reflect their higher donative income, while pooling funds above their grant cap would have a more positive effect on the university as a whole. Adam thinks this could be a way in which “people who really want funding and actually deserve it can easily access it regardless of college,” and a centralised system would ensure that the money would go to those who need it most.

Thus, students from lower income families with limited travel experience, especially those travelling with an academic intention, could use money otherwise left unspent at colleges, or given to recipients who could fund themselves.

Yet centralisation would be by no means easy. As 3rd year Historian Amy Hawkins points out, “while the disparities between college funds are certainly unfair, they are an inevitable symptom of a collegiate university.”

And, considering the response from a university spokesperson, who said “the issuing of travel grants is a matter for individual colleges,” it doesn’t look as if the system will change any time soon.

Data gathered by Sarah Sheard, and refers to number of specific individual grants each college provides. Information provided by colleges and college websites.

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026

News / Gov grants £36m to Cambridge supercomputer17 February 2026 News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026

News / CUCA members attend Reform rally in London20 February 2026 News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026

News / Union speakers condemn ‘hateful’ Katie Hopkins speech14 February 2026 News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026