On the barricades

Daniel Hepworth looks at Cambridge’s history of protests and the art of protesting today

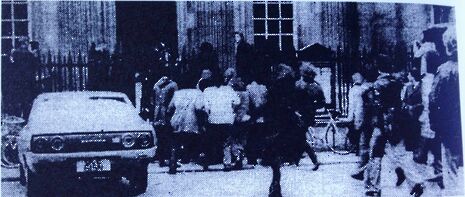

It’s Friday 13th February, 1970. A picket line of 400 Cambridge students surrounds the Garden House Hotel in which a high profile dinner hosted by the Greek Tourist Board is taking place. Protesters are urging guests not to attend, in protest against the military junta ruling Greece. Reports come in that student protesters are drumming on windows and clambering onto the roof. Police take up position outside the dining room; chaos ensues.

Following the now notorious Garden House riot, the hotel claimed for £1,000 of damages for smashed windows and tables. A hotel employee was reported to have sprayed jets of cold water from an upstairs window in an effort to deter the protestors. Thirteen students were arrested and sent to trial after a University proctor was hospitalised having been hit over the head with a brick. Charges against four of the protesters were dropped, although the rest were found guilty of unlawful assembly and served sentences ranging from short periods in borstal to 18 months imprisonment. The sentence prompted an outcry from the then-President of the NUS, Jack Straw, who called the sentences an act of discrimination against students.

This was neither the first nor the last time that violence has erupted from a student protest in Cambridge. November 1967 saw the US Ambassador’s visit to Churchill College prolonged when 300 protesters prevented his departure by hosting a sit-in on the road in a stand against the Vietnam War. Subsequent protests were held against the war during the late 60s, particularly against the American draft program, with anti-war slogans being painted on college walls across the city. In June 1965, a banner attacking American involvement in Vietnam was suspended from the spires of King’s College Chapel. Branches of Barclays Bank were regularly picketed throughout the 1950s due to their investment in South African assets, which many JCRs felt were indirectly supporting the Apartheid regime. One of the largest protests, aside from the Garden House riot, saw the Nursery Action Group (NAG) stage an occupation of Senate House in June 1975, the day before a degree ceremony, over the refusal of the University to provide nursery care for full time students. After a proctor was found to be listening in on their meeting, a vote for direct action was won 105-6 and the group ran down Trinity Street towards Senate House. Although police and proctors locked the doors, 1,600 students managed to occupy the building by climbing in through side windows.

But where does protest stand today? CUSU President Helen Hoogewerf-McComb believes that people still want change, but not always through direct protest: “People make change in a load of different ways: sometimes it is simply sitting down with the right people and having a conversation, sometimes there is power in shouting the loudest and making sure that you cannot be ignored.” She is adamant that student politics should protect this tradition. “While it shouldn’t be our only tool, and it would rarely be the first or only response... CUSU will continue to support students’ right to engage in peaceful protest”.

The protests of the 60s and 70s are not isolated historic incidents. This term alone, two high-profile campaigns have been waged against external speakers at the University. A talk by UKIP leader Nigel Farage was swiftly cancelled last month as students threatened to stage a protest alongside non-student groups. Despite being booked into a formal hall at Corpus Christi by a fellow of the college, Farage’s visit was called off just hours before it was due to begin. Nevertheless, the protest, reduced in size, still took place.

A mere week later, the Cambridge University Palestine Society and sympathetic students picketed against the Israeli ambassador, Daniel Taub, who was speaking at the Union. Protesters called Taub’s presence “deeply insensitive” amid ongoing conflict in the Gaza region. The speech came days after an open letter, signed by leading Cambridge academics condemning Israel’s actions in the region, was released.

The Union, however, insisted that “The Cambridge Union Society does not take a side on political issues, and hosting a speaker does not equate to endorsement of them or their politics.

“We remain completely neutral on these issues and thus consider ourselves distinct from any other activism occurring around the academic world.”

A few activists waging short-lived campaigns against Farage and Taub is hardly a match for the trashing of a high-end hotel, right? 2010 bucked the recent trend of smaller campaigns and saw the country – Cambridge included – engulfed by protests over tuition fees and the scrapping of EMA. Violent clashes ensued with the police as students once again attempted to occupy Senate House, and a handful of students were arrested. This was the largest event seen for many years – the question is, does it still have a place in university life today?

Amelia Horgan, the head of CUSU’s Women’s Campaign, believes that it does: “There are, of course, other ways of drawing attention to issues – whether through committee meetings or petitions – but the Women’s Campaign see protest as a valid... and inherently positive way of trying to change our university”.

However, not everyone is of the same opinion. The Proctors’ Office – which has historically been the University’s first line of defence against protests – insists that opposition should be expressed in other ways. A spokesperson for the Proctors’ Office said that “the defence of freedom of speech… often comes to a head at protests, where defending the right to free speech must always be in the context of lawful and peaceful protest.”

In the past, the Proctors’ Office has sought to limit any radicalism in student unrest, so a more reserved approach to bringing about change is to be expected. Despite this opposition, the belief that the only effective mechanism for change is strong, cohesive, direct action still has significant support amongst students, and student groups are likely to carry on exercising their right to protest.

This is an issue that will continue to test the relationship between student body and University for decades to come. Generally, violence in protests seems to be waning, although it only takes an issue serious enough – such as tuition fees – for there to be a stronger case for direct action. We can only be left wondering what will be the next cause célèbre to get students’ blood boiling.

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024

News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 News / Students organise Cambridge’s first female and non-binary club night25 April 2024

News / Students organise Cambridge’s first female and non-binary club night25 April 2024 Arts / ‘Walking around Robinson is automatically humbling’: college architecture and the psyche24 April 2024

Arts / ‘Walking around Robinson is automatically humbling’: college architecture and the psyche24 April 2024