Rebranding the Women’s Campaign

James Sutton talks to Bethan Kitchen of the Women’s Campaign executive committee about the press, feminism and working-class women

“The Women’s Campaign has been quite sceptical about talking to the press” – not the most auspicious start to an interview. “Equally, one of the things that I’m trying to do is make the Women’s Campaign as accessible as possible.” That’s more like it.

I’m speaking to Bethan Kitchen, the leader of the Women, Class, Access branch of the Women and Class Campaign, in The Fountain, shortly before the group’s first planning meeting.

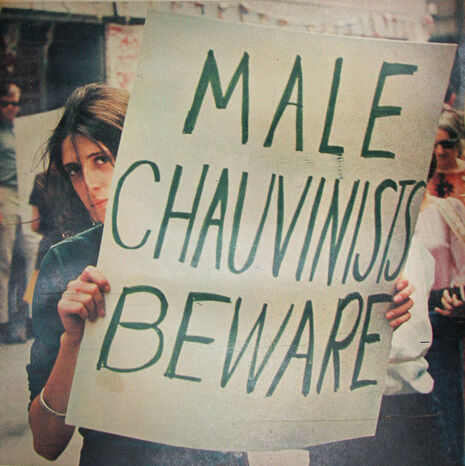

With ‘access’ on the agenda for the evening, I ask Bethan why the Women’s Campaign has a reputation for being inaccessible. “Last year I felt incredibly alienated by the Women’s Campaign in many ways…I felt like the Women’s Campaign was a bit of a friends’ clique, and I didn’t particularly feel as though they necessarily wanted lots of people to join in…I felt like the definition of feminism in the Women’s Campaign was too exclusive.” That’s quite a criticism coming from someone who is now part of the executive committee, having joined in the hope of improving it. Bethan, however, now sees that things are different on the inside, and are changing for the better. “Since I’ve been part of the Women’s Campaign, I’ve soon discovered that a lot of the reasons that I felt alienated were actually bullshit, and that there’s an incredible amount of misinformation given in the press about the Women’s Campaign.” Perhaps I should tread carefully.

Bethan, it seems, wants to change the way the Women’s Campaign is perceived, but is still quick to support the members who have sparked criticism of its approach through outspoken comments on online articles and social media, defending themselves from “outrageously abusive comments…lies, slander, harassment, all that crap”. However, she is also aware that “there have been quite controversial things in the press where the Women’s Campaign might have done things they shouldn’t have, picked the wrong fights.”

“I honestly just don’t believe that anyone on the exec[utive committee] has bad intentions – everyone just wants to make the Women’s Campaign as protective for as many women as possible, and to do really positive things.” I sit in as the meeting gets underway, and Bethan begins to outline her aims for the Women, Class, Access Campaign.

The turnout is not exactly huge – just four in total, all of whom, from their introductions, are currently or have been in the past either Women’s or Access Officers in their colleges. Despite this, the meeting gets underway positively.

It must be said, however, that if anyone is at this point expecting radical feminism with a dash of Marxism, you may as well stop reading. Bethan opens by explaining that she originally “wanted to change a whole system” but has since come to “realise how impossible that is”. Women, Class, Access instead aspires to “doable aims”.

The main topic of discussion for the evening is how to encourage working-class women to consider Cambridge, and Higher Education in general. Bethan tells an anecdote about a Cambridge student who was bullied at school by “chavs”, but now feels as though she got the last laugh “because they’ve got babies and I’m at Cambridge.” Bethan describes to the group how she feels “uncomfortable” with this sort of “problematic” attitude to working-class women, and believes that “women don’t have to compete with each other”.

What’s the plan then? “Something regional in working-class communities” is touted as one possible idea, following in the footsteps of schools and youth groups who are already leading the way in reaching out to young women at risk of exclusion from education, getting involved in crime or teenage pregnancies.

An exhibition or installation featuring artwork produced by working-class women is suggested and generally accepted by the group – although there seems to be a concern that an exhibition would be “quite Cambridgey”. Crossing the class divide becomes a recurrent issue throughout the discussion. Bethan describes her experience of meeting working-class women in a YMCA in Newcastle, explaining that “even though I’m from Newcastle, and my dad has worked with them many times and I was there with him, I still felt like a Cambridge twat.” With mainstream feminsim continuously dismissed as the preserve of the white middle-class, this admission, both frank and honest, is refreshing.

The group agrees that for an exhibition to work, the women involved would need to feel that they owned the space they were working in, that it was truly theirs. How about online, where “all boundaries are down”? General assent.

I slip away as the discussion begins to drift towards specifics. I am, however, impressed by the attempt to redirect the Women’s Campaign’s energies into grassroots outreach projects such as this one. It should, at least, draw less virulent criticism than some of the Women’s Campaign’s other activities. That said, I can’t escape questioning whether there is something a little too developmental in the approach here, and Bethan herself disagrees with “the idea that people should have Cambridge rammed down their necks”. This is only the first meeting, and there’s still time for these problems to be addressed.

Something Bethan said to me before the meeting comes back to me as I walk away – people hold a “prejudice” against the Women’s Campaign, and against “a committee that’s only been here for a few weeks. Mostly it’s completely fresh faces, and we’re instantly getting so much abuse because of a continuous fuelled hatred against this campaign.” Whilst we all see the headlines about the vociferous side of the Women’s Campaign, it hardly seems fair to tar the whole Campaign and its brand new committee with the same brush; especially while there are those who are trying to give it a makeover.

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025 News / Gov declares £31m bus investment for Cambridge8 December 2025

News / Gov declares £31m bus investment for Cambridge8 December 2025 Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025

Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025 News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025

News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025 Lifestyle / Into the groove, out of the club9 December 2025

Lifestyle / Into the groove, out of the club9 December 2025