Interview: Tony Benn

Described by some as Britain’s foremost socialist, former Labour Party MP and current President of the Stop the War Coalition talks to Isabella Cookson about his life in politics

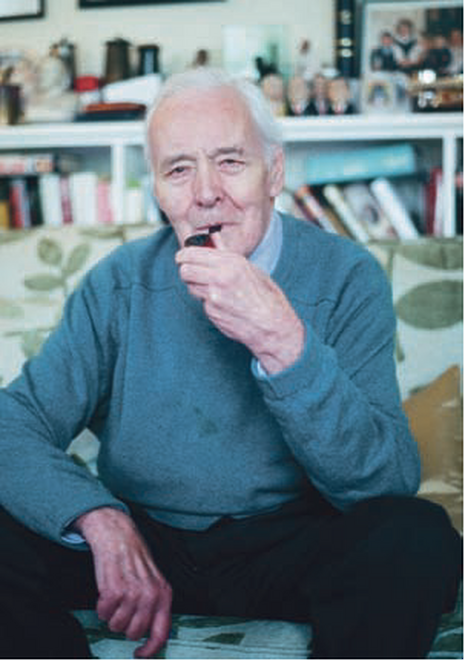

He was just five years old when he first visited number 10 in 1930 and can remember sitting at Gandhi’s feet during the Indian leader ’s visit to Britain a year later. Benn, now 87, greets us in his small flat in Notting Hill: his beloved, characteristic pipe in one hand, his obligatory cup of tea in the other. The room is filled to the brim with pictures, cards and trinkets, while the walls are covered with photographs of his grandchildren: family is clearly very important for Benn.

Both Benn’s grandfathers were politicians and his father was a Labour MP. His mother, a feminist theologian, had a remarkable influence upon him. “We used to read the Bible every night. She taught me that every political issue is really a moral question. It shouldn’t be about whether or not it is profitable, it should really be about right or wrong”.

Benn recalls the lively political discussions at home, describing when his father received his title, “and so I became the heir. From the time I was elected I knew that when my father died they would throw me out. I tried to get rid of it and they wouldn’t let me. They disqualified me from running for Parliament.”

He fought to retain his seat in a by-election called on May 4th 1961, caused by his succession. “I was elected with a far bigger majority than when I was qualified,” he smiles, “Then they took me to court and there was such a row that it became clear that there would have to be a change. But the issue wasn’t really me, the real issue was the right of the people of Bristol to pick who they wanted. Why should the fact my father was a peer prevent them from choosing who they wanted to represent them in Parliament?”

Benn has certainly not wavered when it comes to his opinion on the House of Lords. He believes that the House of Lords should be an elected, not an appointed, chamber and that the Head of State should be the speaker in the House of Commons. “If I went to an untrained dentist who could only assure me that his father was a really good dentist- well, I wouldn’t stick with him!” We can keep the Royals though, he concedes – that is, so long as they don’t have any political power.

Such beliefs have stuck with Benn over the years, but has fifty years under the political spotlight changed any of his ideas? “Well, I’m an old man now and I have learnt an enormous amount and have made a million mistakes. I don’t think making a mistake is wrong- that’s how you learn. The only thing I hope I haven’t done is said anything I didn’t believe in, in order to get on.

One of the big issues I changed my mind on was nuclear energy. I remember when President Eisenhower came out with the “Atoms for Peace” policy, saying that we could use nuclear energy to make electricity. A lot of people, including myself, were terribly excited by that, they said it’s cheap, it’s safe, it’s peaceful. I ran the nuclear energy programme for many years and what I learned as the minister was that it isn’t cheap because they still haven’t worked out the cost of storing the nuclear waste, it isn’t safe – Chenobyl, Hiroshima, the Three Mile Island – and it isn’t peaceful, because although the programme was said to be about energy, it’s really about the bomb. I discovered that all the plutonium from our civil power stations was sent to America for their weapon’s program. So every civil nuclear power station in Britain was really a bomb factory for the Pentagon.”

Benn left parliament in 2001, stating famously that he did so in order “to devote more time to politics.” He explains how this freed up time to spend campaigning for issues he believes in, rather than specific party policies.

“If you look at how progress over history is made, it is always when people have campaigned. That’s how the women got the vote, how we got the health service, and why the death penalty was abolished. Pessimism is an instrument used to destroy hope and without hope you’ll never have a successful campaign. So, I’m always very nervous when people say “nothing ever changes”, because I know that’s not true. So never be cynical to the point that you don’t put the effort in, that’s all I’d say.”

During the lead-up to the war in Iraq in 2003, Benn made the controversial decision to interview Saddam Hussein as a part of the Stop the War Coalition’s campaigns. He was, in his own words, “hammered” by the press for talking to the enemy. The equipment for the interview was provided by Saddam Hussein himself and was broadcast on Channel Four.

“I put simple questions to him. I asked, ‘Do you have weapons of mass destruction?’ He said ‘no’. Well, I didn’t know whether to believe him or not. But, they never found any. I said, ‘Do you have links with Al Quaeda?’ He said ‘No’. I knew that was true because Osama Bin Laden hated Saddam because Saddam was a secularist.”

When asked what Saddam was like as a person, he replies “He was very friendly personally to me”, before pausing for a while to stare down intently at the pipe he’s been fiddling with throughout the interview. He slowly continues, a subtle note of conflicted emotion creeping into his voice: “He’s the only man I’ve ever known executed. It was a horrible sight to see the man you’ve talked with just a few weeks before with a rope round his neck”.

One thing is markedly clear throughout the interview: Benn may be 86 but he is as opinionated and as engaged with current politics as ever. He thinks that Ed Milliband will make a good prime minister, children should be able to vote at 16 and that Cameron made the “right move but probably for the wrong reasons” for vetoing the EU-wide treaty change over Eurozone rules. Politics, he believes, “is a vocation, not a career”.

But although politics has been his life, he would like to be remembered not for any significant political change he was involved in but simply, “that I’ve encouraged people. I think the function of the old is to encourage the young. If you can encourage people, they will be ten times stronger. I would like on my gravestone to be written: ‘Tony Benn, he encouraged us.

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026

News / Hundreds of Cambridge academics demand vote on fate of vet course20 February 2026 News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026

News / University Council rescinds University Centre membership20 February 2026 News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026

News / Judge Business School advisor resigns over Epstein and Andrew links18 February 2026 News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026

News / Petition demands University reverse decision on vegan menu20 February 2026 News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026

News / Caius students fail to pass Pride flag proposal20 February 2026