Gertchen Duschke-Klotz on her ‘barbaric, beautiful’ life in 1960s Cambridge

The wife of Rudi Dutschke, spokesman for the German 1960s Student Movement, talks to Fabian Stephany about revolutions, feminism and their time in Cambridge

Gretchen Dutschke-Klotz (GDK) is a contemporary witness of German history. She tells the story of how the 1960s Student Movement in Germany ultimately transformed the country to a modern and democratic society. At that time, Germany was still struggling with its undemocratic past. The idea of a democratic system, GDK remembers, had been installed by the allies but was not yet deeply rooted in the German society. Many parents of the 68 students did not want to talk about their role in Nazi Germany, but the young people were striving for answers.

In the late '60s, the initially peaceful and moderate student demonstrations started to polarise the German society. Conservative politicians and media outlets demonised the peaceful students and a small radical offspring of the movement started to separate into factions with a propensity towards violence.

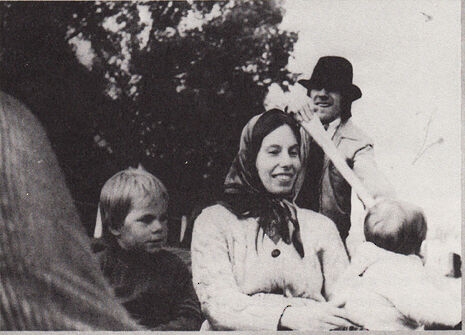

Whenever GDK resumes speaking about the historical changes, she also tells the story of her “barbaric, beautiful” life with her husband, Rudi Dutschke. Rudi Dutschke had become the representative for the German Student Movement in the early '60s. The unrest related to the protests of the left-wing students which sent the German political landscape into turmoil a couple of years later. Conservative Springer press had started to stigmatise Dutschke as an enemy of the State.

On the morning of 11th April 1968, Rudi was waiting outside a pharmacy to collect medicine for his baby son, GDK tells us, when a young anti-communist, Joseph Bachmann, walked up to Dutschke and fired three bullets at him. Dutschke miraculously survived the assassination attempt but decided to leave Germany for the United Kingdom, where he hoped to recuperate from his heavy brain damage. The Dutschkes moved to London and half a year later to Cambridge.

GDK remembers her time in Cambridge with mixed feelings. “It had been clear from the beginning that our stay in the UK could be terminated at any point in time.” In December 1968 the Dutschke family was admitted to the UK; James Callaghan, former Home Secretary, required Rudi Dutschke to agree that he would not engage in any kind of political activity during his time in England. This “landing condition” was extended again by May 1970, when the government had changed and Ted Heath had become the new Conservative Prime Minister. GDK recalls the strong support from Clare Hall and King’s fellows during this time of uncertainty in Cambridge. “The acquaintances and friends we made in Cambridge provided us with great support in this nervous time.”

Meanwhile, Rudi Dutschke had accepted a research position at Clare Hall. On 25th August 1970, the Home Secretary refused to prolong the “landing conditions” in the interests of national security. Rudi Dutschke never took up his Cambridge studentship. After a much criticised trial, he was forced to seek shelter in Denmark, where he was offered a position at the University of Aarhus. He died in Aarhus in 1979 after continued health problems due to his brain damage.

Just like her husband, GDK herself hesitated to actively engage in politics, at the beginning. Then and now, she underlines the role of women in societal change. In the '60s, female protesters, on a larger scale, had a voice in the process of political formation for the first time in German history. Bold women did not shy away from conflict, even within the movement. One of GDK’s colleagues, Sigrid Rüger, once threw tomatoes at her male colleagues, who had ignored the talk of the first women speaking at the main assembly of the Students’ Movement in 1968. “Quite a funny, but most of all, a historic scene for the movement”, GDK grins.

Without the different female-led political groups, the new ideas of the ‘60’s movement about gender equality and female self-determination would not have spread to the society as a whole. “Compared to the ‘60s many things have changed for the better”, GDK says, when she recalls the pictures of many dads with baby buggies on the streets of Berlin. Similarly, political leadership was unreachable for women at that time. The women wanted to change the way politics was made, by men. Over the last decades, more and more women had the chance to enter politics, but the system itself did not change.

“It is likely that individual political actors, both male and female, can be quite successful with a destructive political agenda. For example, even though, Hillary could be the first female president in the history of the United States, I would vote for Sanders. Contrary to Hillary, he voted against the wars (in Iraq and Afghanistan). Hillary on the other hand, might start a new war.”

GDK is sure that no one-sided action can change the system. It needs both men and women, together, to alter the way our world works.

With thanks to the MML faculty and Dr. Katharina Karcher, who researches and writes about the topic, for making this interview possible.

News / Scammers posing as deaf fundraisers target students around Sidge6 March 2026

News / Scammers posing as deaf fundraisers target students around Sidge6 March 2026 News / Melanie Benedict elected SU undergrad president6 March 2026

News / Melanie Benedict elected SU undergrad president6 March 2026 Science / Why Cambridge rocks6 March 2026

Science / Why Cambridge rocks6 March 2026 News / Cambridge psychiatrists back gender clinic study6 March 2026

News / Cambridge psychiatrists back gender clinic study6 March 2026 News / Open letter criticises honorary doctorate for leader of Hong Kong university6 March 2026

News / Open letter criticises honorary doctorate for leader of Hong Kong university6 March 2026