Tin Machine and Cambridge: Bowie’s forgotten era

When Bowie took to the Corn Exchange in 1991, he revealed a side of himself he would never show again

In classical tragedy, a hero’s greatness can only be realised because of their failings. With this in mind, we can perhaps only appreciate the heights of David Bowie’s oeuvre because he also released 1967’s ‘The Laughing Gnome’, a song notable for all the wrong reasons. However, it’s far too easy to overlook the “failed” projects of an artist’s career, especially when Bowie’s discography is known for its ch–ch–changes…

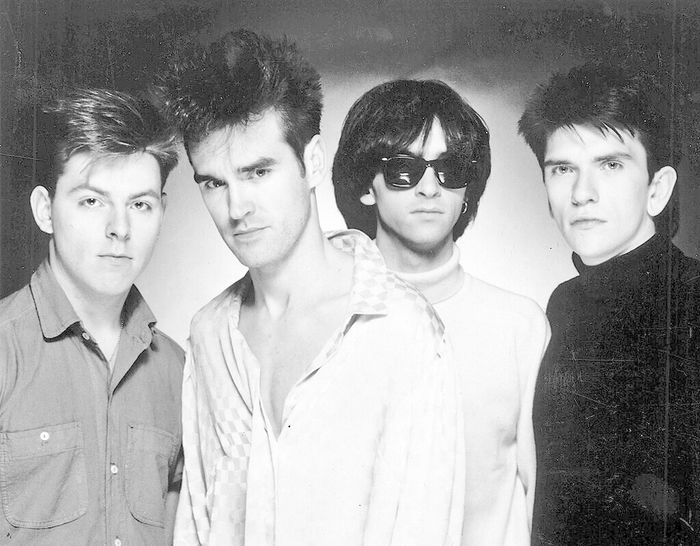

For instance, even some of Bowie’s most ardent admirers have forgotten his brief stint as a member of Tin Machine, which, in 1991, took to the stage of Cambridge’s Corn Exchange on their It’s My Life Tour. Formed in 1988 with the aim of recapturing the energy of rock and roll, the group consisted of Reeves Gabrels on guitar, who would later work with the Cure, and the Sales brothers – the same rhythm section that played on Iggy Pop’s 1977 classic, Lust for Life. Almost 20 years earlier, Bowie had strutted the same stage as the ethereally glamorous Ziggy Stardust, just before Ziggy became legendary. Though long forgotten, it is worth remembering this strange Bowie side-project and its connection to Cambridge; it was not a side of himself he would show again.

“The Bowie that rose from those ashes was a far cry from his formerly slick image”

By the late 1980s, Bowie was exhausted. While it may still deservedly grace dancefloors today, 1983’s Let’s Dance was also a kiss of death to Bowie’s creativity. Each album that followed seemed fixated on re-creating its commercial success. Those attempts, 1984’s Tonight and 1987’s Never Let Me Down, were at best poor imitations and, at worst, abominations (look up his Pepsi commercial at your peril). The Glass Spider Tour, which promoted Never Let Me Down, became a notorious example of eighties excess; it was neon and garish with no substance behind its spectacle. Music legend states that Bowie burned down the set of the titular Glass Spider to purge the experience from popular consciousness and refresh his image.

The Bowie that rose from those ashes was a far cry from his formerly slick image. First of all, he had a beard. He was also now a member of a band, Tin Machine. By stepping away from the spotlight, Bowie regained some of his creative freedom. His music anticipated American grunge and his lyrics became political; the title track of 1989’s Tin Machine directly targeted Thatcher and her Tory cabinet, decrying how they were “carving up my children’s future”. Anger pervades the whole album. ‘Under the God’ depicts a world overrun by “rightwing dicks in their boilersuits”, while Bowie’s rendition of Lennon’s ‘Working Class Hero’ is drenched in righteous bitterness. There are many underrated gems across the album, especially ‘I Can’t Read’. A lament sung by a broken Bowie, it carries genuine pathos. The “15 minutes of fame” Bowie craves seem to refer to his experience of the 1980s and the unwanted attention they brought him.

While touring Tin Machine, Bowie played venues he hadn’t visited since the early 1970s. Putting aside spectacle, these concerts returned to the essence of a “rock concert”. That is why Bowie returned to Cambridge in 1991. Having performed to 60,000 people in Milton Keynes the previous year, Bowie was now playing to an audience of under 2000. People queued all night outside the Corn Exchange to buy tickets, which sold out within hours. By 1992, Tin Machine would be over and Bowie would go back to selling out arenas. He would never return to Cambridge.

What the concert provided was a renewed continuity with the younger Bowie: the Bowie that played Jesus May Ball in 1970 and the freshly energised Ziggy Stardust of 1972. While the music of Tin Machine may be forgotten, its impact on Bowie’s trajectory cannot. Returning him to smaller venues and the roots of his music, Tin Machine allowed Bowie to escape the plastic pop and the superficial spectacle he reviled. There would be no comeback, no Blackstar or Lazarus, without a return to the experimentation that defined his career. Now ain’t that just like Bowie?

Comment / Cambridge is right to scrap its state school target1 May 2024

Comment / Cambridge is right to scrap its state school target1 May 2024 News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024

News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024 Sport / The diary of a Bumps rower24 April 2024

Sport / The diary of a Bumps rower24 April 2024 Features / Will May Balls ever be sustainable?30 April 2024

Features / Will May Balls ever be sustainable?30 April 2024 News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024

News / Emmanuel College cuts ties with ‘race-realist’ fellow19 April 2024