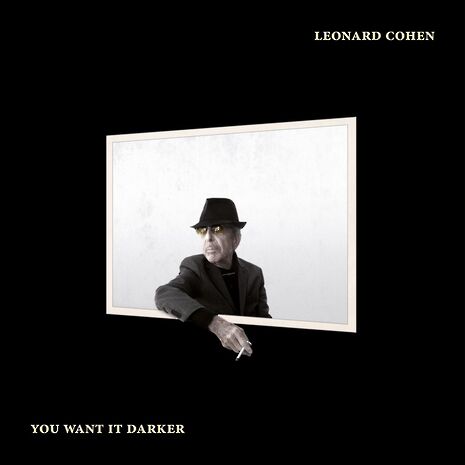

Leonard Cohen – You Want it Darker

Cohen’s final album is one to remember

Forty-five seconds into the title track of his final album, You Want It Darker, Leonard Cohen plays his grand trick. Up until this point, the song has sounded exactly as we’d expect it to: the defeated lament of a dying, octogenarian crooner. “If you are the healer it means I'm broken and lame”, he sings. Cohen’s protagonist isn’t dead yet, but his wounded sigh to God isn’t a million miles from David Bowie’s “look up here, I’m in heaven.” But the defeatism is a red herring, an act. Cohen indulges our assumptions, letting us smugly make our judgement of the album before the first song has even run its course. Then, 45 seconds into the track, he smashes those assumptions aside.

“You want it darker. We kill the flame.” “You” is God, and Cohen begins to viciously attack him for allowing death and allowing suffering, for his constant inaction in the face of atrocity. Humanity, he says, is God’s instrument, bringing cruelty into the world to fulfil his black-hearted desires. We kill the flame when God wants it darker. And Cohen’s character is suddenly no longer “broken and lame”, but someone who wants “to murder and to maim”, recalling the ruthless world-dominators he played on ‘First We Take Manhattan’ and ‘The Future’. He makes specific reference to the Holocaust, and the instrumentals skeletal beats and ghostly backing choirs only blacken the darkness. ‘You Want It Darker’ isn't a question – it’s an accusation. Cohen accuses God of failure.

It’s a jarring moment that trashes any preconceptions of the album’s intentions, and Cohen’s power to shock with just a few lines is reflective of his legitimate skill as a poet. But for every bold statement like this attack on religion, there’s a counterpoint. Most of the songs on this brief record are more complex and less argumentative than "You Want It Darker’. ‘I’m Leaving The Table’ acknowledges the reality of the “broken and lame” lyric, sounding really defeated as it documents a collapsed relationship, while ‘Treaty’, the prettiest song here, is full of its own contradictions, both a sincere confession of love and a cynical take on a partnership held together by diplomatic agreement. Religion comes up again, but it’s approached from different perspectives; ‘Treaty’, for example, has the biblical serpent shedding its skin in a desperate attempt to atone for its sins. Cohen’s poetry has always shunned one-sided arguments in favour of explorations of the complexities of human beliefs and emotions, and ‘You Want It Darker’ is much subtler and more interesting because of this.

The music holds the album together and prevents Cohen’s thinking becoming too disjointed; eerie title track aside, the songs are midtempo, bluesy and smooth, full of playful diversions like the guitar solo in ‘If I Didn't Have Your Love’ and the strings which punctuate the verses of ‘It Seemed The Better Way.’ Cohen’s voice helps too, more gravelly than ever and so soft spoken that he could be whispering in your ear, delivering a real sense of intimacy. The album is aural honey, perhaps the most singularly beautiful in Cohen’s canon and equally enjoyable whether pouring over the lyrics with a notepad and pen or sprawled out on the sofa with a glass of wine in your hand. As Cohen breaths his final line “I wish there was a treaty between your love and mine”, the sound swells and becomes almost too beautiful to bear. It is deeply sad.

The album, particularly the furious first song, wouldn’t have been the same had Cohen not recorded it while ready to die and smoking medical marijuana to ease the pain of his cancer. But it wouldn’t have been profoundly different either, because Cohen ended his life more interested in continuing to examine the themes which preoccupied his art for over 50 years than in simply transcribing his own death. You Want It Darker is not a last will or the full stop and the end of a sentence; it is a gorgeous exploration of the human soul, littered with love, loss, belief, heartbreak, anger, humour and, of course, mortality. The album is beautiful, and it is a terrible shame that Cohen’s exploration must now come to an end

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025