A new age for the album

Columnist Perdi Higgs writes about the transformation of albums from a collection of singles into a work of art

For major music releases in 2016, it is never just an album – it is an aesthetic. By ‘aesthetic’ I mean a vibe: the music is translated into tangible forms of expression. Kanye’s Life of Pablo is an aesthetic. It is a colour palette, a clothing style, and an attitude. The release of an album, mirrored by complementary artistic expressions.

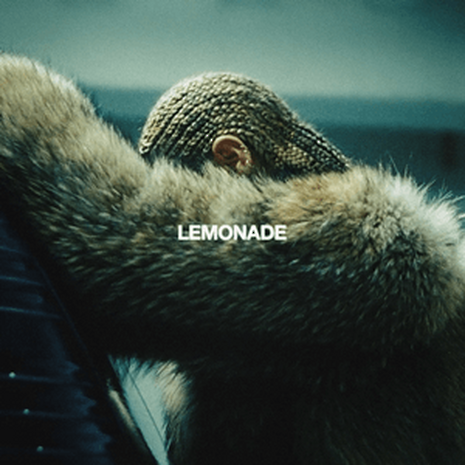

The concept of this is undoubtedly appealing, and appears to counteract an issue of music streaming culture where people only listen to a single song, rather than taking the time to experience the album as a whole. There have been efforts to counteract this: for example, the creation of so-called ‘visual albums’ that encourage the listener to appreciate an album in its full form. Beyoncé’s Lemonade short-film is an example of this, releasing an album upon multiple different platforms – developing a musical, visual and wholly artistic presentation. Creating an album aesthetic is another way of encouraging an individual to appreciate an album in its whole form, using creative and thematic elements to present the piece as holding its own unique ‘aesthetic’.

For music releases, it calls the listener to appreciate an album based upon individual tracks, and in a fuller sense. This theory seems to be proving true. For example, Life of Pablo: while Kanye released the ‘Famous’ track as a successful single, it is as a whole work that it has been discussed by the media. It appears as more of an art form; a collective piece that can be reflected upon as an ‘era’ of an artist’s career.

At the same time, it’s kind of a starkly obvious marketing strategy. As Life of Pablo becomes an aesthetic in its own right, you have teenagers paying $200 for a t-shirt that says “I feel like Pablo”. So there is something irritating and a bit soulless about it.

This autumn, when Frank Ocean finally released his album Blond, it was accompanied by the ‘Boys Don’t Cry’ zine – and once again, an album is given an aesthetic. The zine contains photos of mysterious figures in a colour scheme that matches the album art to perfection. The long-delayed, painstakingly created album is passionate and moving, but the seeming ‘trendiness’ of its promotional efforts can make you question whether people are buying into the aesthetic or the actual music.

This is not a criticism of marketing or promotion in general; obviously that is an integral part of the industry. The questionability of the so-called ‘album aesthetic’ is that it can make you doubt the centrality of the music within all of this.

That sounds overly cheesy but we can’t deny that it matters. If someone is making a form of ‘immersive cultural experience’, where an album is part of collection with a short film, interpretative dance and an art collection, that’s really cool. But then what happens if you just listen to the music: are you missing out on the true experience if you only take in one platform?

These platforms can work to build one another up. When Andy Warhol first debuted the Velvet Underground band in New York City, they were part of a whole night of Warhol’s own ‘aesthetic’. Graphic films projected on the walls, with screeching guitar music deliberately designed to unsettle the audience. In this, the performers were arguably part of a wider art statement. Yet through this multi-platform performance approach, Nico (under the direction of Warhol) produced one of the most critically acclaimed album rock albums of all time. So perhaps, judging the pop-up stores and zines of 2016 is too cynical.

With the effort taken to create an album, in a time where a song is instantly streamed and either ‘saved to library’ or ignored, artists are likely to search for a way for their work to be fully acknowledged. Creating an album is art, and an artist has a right to want to exhibit their work in the most moving and interesting ways possible. Creating an aesthetic helps to give a real sense of the intentions of the artist.

It is a visible, readable, and wearable manifestation of the album, making it the most powerful ‘cultural’ statement it can be

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025 News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025

News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025 News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025

News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025 Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025

Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025 Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025

Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025