Finding beauty in the banal in student short Tickets to Earth

Oliver Bevan sits down with student filmmakers Aurelia and Fin to talk about their out-of-this-world sci-fi short that explores what happens before you’re born

“There are a lot of films that look at the afterlife. I wanted to flip that and look at what happens before you’re born,” says writer-director Aurelia about the conception of her short film Tickets to Earth. “I had this image of a woman who goes through life a bit depressed and doesn’t see the point in living. So I though, how would this change if she knew that she’d chosen this life herself?”

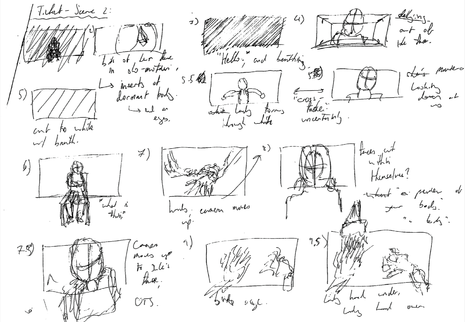

Tickets to Earth has been in the works for over a year, and is finally due to be screened on 5th March at St John’s Picturehouse. The role divisions, Aurelia as writer/director and Fin as Director of Photography, have been fluid since the beginning. Aurelia came up with the initial idea in her final year, and contacted the Preston Filmmaking Society, which Fin had established with the goal of funding student films. The pair then worked on the script and storyboard together. Fin spent hundreds of hours editing the film. Aurelia recalls the process, “considering we had eight days, twelve locations and nineteen people in the final two weeks of a Cambridge term, it’s a miracle that this film even exists!”

“Considering we had eight days, twelve locations and nineteen people in the final two weeks of a Cambridge term, it’s a miracle that this film even exists!”

Fin describes the short as a surreal meditation on the “joy, pain, and sublimity of being alive.” We spend the forty minute runtime moving seamlessly between the quotidian life of Jule, a struggling university student, and a surreal “cosmic” space where Jule’s soul is being primed for earth before she is born. It centres around the idea that each and every one of us has chosen to be here and that we are lucky enough to find a body. As the film’s title suggests, “there is a limited number of tickets,” in other words a limited number of bodies through which we can experience the wonders of earth. Aurelia explains her thinking behind the concept: “If I knew I had chosen to be here and wanted to experience life, and that it was a privilege to do so, then I would enjoy life more. I think we’d all be a lot more consoled.”

When I ask whether the film’s existentialist stance has any personal resonance with them, Fin clarifies that it is “more of a prism through which to consider these issues. [...] It’s not our statement on how we believe the world to be.” From early on, they “did not want to tell anyone the cosmic truth of how to live their life.” Aurelia is equally enthusiastic to hear about my own interpretation of the film. It’s “constructed so that everyone will interpret it differently. Some might see it as depressing, others as uplifting. Some as cheesy, others as serious. I’m really curious about the breadth of the film’s reception.”

“If life is just peace, love and happiness, then is there really any growth?”

At first, I found Jule’s life on earth to be characterised by a persistent emptiness, whether it’s her rushing to her lecture late or looking lost in a crowded nightclub. Fin agrees, “there’s an excitement, a momentum, a profundity in the cosmic space that Jule cannot find on earth.” However, “it’s not supposed to be disappointing. We want the audience to find value in Jule’s life that she cannot see for herself.”

Aurelia adds, “if life is just peace, love and happiness, then is there really any growth?” She later points out that even the objective of “growing” already indicates the pressure to do something. It’s enough just to observe our experiences instead of judging them. “These are the basics of mindfulness.”

The emotional and sensory experience of life hence appears at the centre of the project. Aurelia gesture’s in particular to the soundscape: “The use of sound and foley was important in adding texture to earth scenes, a texture that you don’t get in the cosmic space.” The earth scenes also display a roughness and inconsistency, especially when compared to the pristine treatment of light and composition in the “cosmic” white room. This roughness is deliberate. It is part of everyday life. Further drawing the audience into Jule’s consciousness, Fin emphasises his reluctance to use long lenses. “I like being close. There’s something about the micro effects of the face and the emotion that individual objects hold. When you’re close to something, it suddenly takes on a kind of life.”

For a Cambridge student, the specifics of Jule’s life are instantly recognisable, with scenes shot around the Botanical Gardens, Sidgwick site, and even MASH. Though Aurelia emphasises their avoidance of distinctly Cambridge college exteriors to instead represent a more universal student experience. After spending weeks cycling around the hill colleges trying to find a location for the white room, the team were eventually allowed to film at the Heong Gallery. All the cosmic scenes were filmed there in one day. And, if you’d had an eye out, you could’ve caught a glimpse of Fin aboard a Voi weighed down by camera, sound, and lighting equipment.

Asking what their takeaway from the project was, they start to meditate on the Cambridge film scene more generally. Fin sees the film world at Cambridge opening up. “There’s growing interest and there really should be. I’d like it if the film world at Cambridge could be, in any way, as expansive as the theatre world.” With a total of fifty Cambridge students working on the film and no professional help, Tickets to Earth was an ambitious project. Fin and Aurelia hope that their success will encourage more people into the Cambridge film scene. In Aurelia’s words, “you don’t need a lot of equipment. In the end, it’s all about the story you want to tell.”

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024 News / Gender attainment gap to be excluded from Cambridge access report3 May 2024

News / Gender attainment gap to be excluded from Cambridge access report3 May 2024 News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024

News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024 News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024

News / Academics call for Cambridge to drop investigation into ‘race realist’ fellow2 May 2024 Comment / Accepting black people into Cambridge is not an act of discrimination3 May 2024

Comment / Accepting black people into Cambridge is not an act of discrimination3 May 2024