Review: How was ‘O.J.: Made in America’?

Lillian Crawford extols the virtues of this incisive and unrelenting documentary…

Clocking in at 467 minutes, Ezra Edelman’s landmark documentary feature, O.J.: Made in America, is the longest film to win an Oscar. Its predecessors could not be more different: Gone with the Wind, Lawrence of Arabia, War and Peace. Epic romances filled to the edges of the screen with extras come to mind. And yet, possibly even greater in scale is a documentary about a single man which everyone, no matter how much they know beforehand, will come out of with a new outlook not only on O.J. Simpson, but on race, celebrity, and law.

Rest assured, Edelman does not waste a minute of its runtime. Painstakingly compiling footage and photographs with 72 new interviews, the story is told from every angle, including, through personal writings and recordings, the subject matter himself. Looking into the eyes of these characters is at times deeply unsettling, as the racism and ignorance of certain interviewees comes to light, notably LAPD’s Mark Fuhrman. Even more disturbing are the close-ups of Simpson’s own face, slowly transforming from youthful sportsman to a shell of excess and denial. It is an image that will not leave you when you go to sleep that night.

“Looking into the eyes of these characters is at times deeply unsettling, as the racism and ignorance of certain interviewees comes to light”

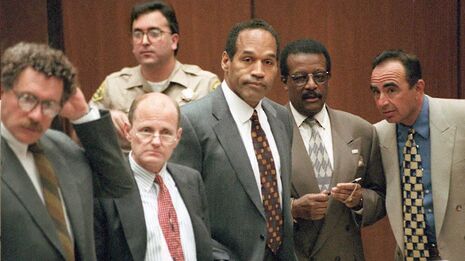

Nevertheless, sufficient distance is created for an audience to make their own judgement, with both prosecution and defence given a voice in the middle section dominated by ‘The People Vs. O.J. Simpson’ trial of 1994 to 1995. Particularly remarkable is the number of key figures that share their thoughts, from lawyers to jurors. This is at times emotionally challenging, witnessing people struggle to admit their mistakes, especially those who idolised and loved a friend they later realised savagely murdered two people they also adored. It is through their narratives that we are grounded from judgement, and reminded of the benefit of hindsight

It is then the charismatic façade Simpson created that allows a macroscopic investigation into the media and celebrity culture. This was an individual obsessed with fame to the point that anyone that met him or saw him on television appears to have been totally enamoured of him. Alongside the images of his brutality to his wife, some of the most disturbing footage in the film is of people claiming to ‘know’ he was innocent, because he was a great football player.

It forces us to look at the media in our own time, at celebrities like Casey Affleck, Johnny Depp and Mel Gibson, for example. If a layman is accused of sexual harassment, they may never find work again, and yet, through popular refusal to believe these people are incapable of crime due to their success, the majority are willing to turn a blind eye. Around the halfway mark, a photo of Simpson laughing with a young Donald Trump fills the screen in a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it moment. It may just be the most telling image in the whole film.

There is not space in a review to do justice to a film like this, and perhaps even more significant than the theme of media culture that runs through the film is that of race and civil rights. Following the ‘#OscarsSoWhite’ controversy of last year, cinemas have been filled with a backlash against it. Moonlight, Fences, and Hidden Figures, each a uniquely remarkable film, draw from real experiences in a dramatic style to tell the stories of black people in America. However, the real breakthrough in exploring attitudes of white and black people towards each other, regarding law and self-perception, is a documentary that expertly contextualises one figure in a much bigger issue, and, in doing so, removes the self-importance this egomaniac believed himself to have.

A challenging and often chilling watch, Ezra Edelman’s magnum opus is a reminder of the power and scope of documentary filmmaking. In uncertain times of increasingly racist politics and media culture, the story of O.J. Simpson seems to be as relevant now as it was in 1994-5. Much like Moonlight, it will stand as a revolutionary landmark in the future of cinema

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025