An Idler life

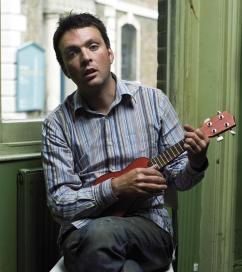

, editor of The Idler and bestselling author of How To Be Free and How To Be Idle, tells how to get out of the rat race

Tom Hodgkinson missed the start of this interview, for which he gives a slightly unexpected excuse: “Sorry, I was taking a long bath.”

But then again, this should come as little surprise from a man who has made a career out of telling people to slow down, stop working so hard and remember how to enjoy life. He’s an engaging interviewee, a curious and passionate speaker with a strong sense of humour.

Disillusioned with the world in which he found himself on graduating from Jesus, in 1993 he and his chum Gavin Pretor-Pinney (whose book 'The Cloudspotters’ Guide' now adorns many a student bedside table) founded The Idler, a magazine set up on “the conviction that laziness has been unjustly criticized by modern society, and that it deserves to have its good conscience returned to it”.

The bi-annual publication attracted a small but devoted army of fans, including a wealth of our prominent cultural figures - the likes of Will Self, Damian Hirst, Pete Doherty, Michael Palin, Bruce Robinson, Alan Moore, Jeffrey Bernard and Douglas Coupland have all featured in one issue or another.

What began as a personal aversion to the 9 to 5 gradually became a philosophy, a reaction to the entire notion of the Protestant work ethic, whichwith the Industrial Revolution and has been getting worse since. The message is not “don’t work”, but rather to use your time better, and spend more time doing the things you want to do, rather than those you feel obliged to. And one of the other tenets of the philosophy is that great works are often achieved after long periods of inactivity, or “thinking time”. Hodgkinson calls these moments “paroxysms of diligence”, but it’s a way of working familiar to many.

Eventually the magazine spawned the books “Crap Towns” and “Crap Jobs”, as well as Tom’s manifestos for better living, “How To Be Free” and “How To Be Idle”. The latter book advised, among other things; more conversation, drinking, smoking, slower eating, slower sex, gardening, lie-ins and, most importantly, forgetting the idea that you need to be rich to enjoy a rich and productive life.

But he began down a path that rings far too true for many of us. On leaving school he read English at Jesus, where he divided his days “reading books, playing in bands, editing magazines and watching great lectures”.

So it came as a bit of a shock to leave Cambridge and find that the whole world suddenly revolved around the need to get a job, to earn money for things you don’t really need. It’s something he still feels particularly strongly about.

“Education isn’t an investment in the hope that it will get you a good (i.e. highly paid) job at the end. Jobs are crap. Students are assuming that because a consulting job starts on £25k, it is necessarily a good thing. You will be humiliated, and then promoted to a position where you can humiliate others. And that’s your life.”

Surely some money is important, I suggest, for paying for things? And if nothing else for the security to enjoy the pleasurable life he advocates so strongly. His response is quick and, after a while, obviously true: “Just reduce your outgoings a bit. It’s simple. We grow our own vegetables, which is not only cheaper but nicer, too, and we stopped buying newspapers and magazines, because we realised that we were probably spending a thousand pounds a year on them.”

The magazine itself is actually in its third incarnation having been originally founded by Samuel Johnson, a man famous for his affection for the good life, and one of Hodgkison’s “Idle Idols”, who said, in one of the pithy one-liners he seems to have spent his life specialising in, that “the happiest part of a man’s life is what he passes lying awake in bed in the morning.” Many an arts student will know what he means, and scientists will wish that they did.

After Johnson’s death the magazine was abandoned until the late 19th century, when it was taken up by Jerome K. Jerome, author of one of the seminal works of Idler literature, Three Men In a Boat, and another confirmed man of leisure. Unfortunately it folded - it has never been a wildly profitable venture - until Hodgkinson picked up the baton again.

“What I find depressing is that some quite good people have been saying what I’m saying in books and essays for thousands of years and it just seems to have gotten worse. I don’t put much faith in the political system because it’s a question of how are you going to run capitalism, not how are we going to develop a different system to capitalism.”

“What I find depressing is that some quite good people have been saying what I’m saying in books and essays for thousands of years and it just seems to have gotten worse. I don’t put much faith in the political system because it’s a question of how are you going to run capitalism, not how are we going to develop a different system to capitalism.”

He considers himself an anarchist - despite the laid-back nature of the Idler, there is a strong streak of protest in much of his writing, although the enemies are not the sweatshop or the despotic regime, but our own “englightened” Western, work-obsessed culture. He’s quick to interrogate me about the University, wondering if the fires of student protest are still burning. I tell him that protest and radicalism are now side-issues, taken up by those with too much time or too little soap. His response is indignant: “Where is your free spirit? How are you going to create anything worthwhile? The point of University is to make trouble.” It is a point well, if often, made, but one of the more attractive things about Hodgkinson is that he has followed his own advice - he and his family moved out of London to an old farmhouse in Devon, where he is currently writing a book about Idle Parenting.

Not to let his alma mater down, he’s planning a trip to Cambridge in Lent term to give an “anti-careers fair”, where “interested (and interesting, he adds) students can come and learn more about the development of a freer life.”

“Listen to ‘Anarchy in the UK’”, he urges, “Read ‘The Revolution of Everyday Life’ by Raoul Vaneigem, learn the ukulele, bake your own bread, reject the supermarkets, cut up your credit cards, go fishing, wr ite more, read more. Take back your time”. Something for everybody there, you would think.

Alistair Unwin

News / Academics lead campaign against Lord Browne Chancellor bid2 July 2025

News / Academics lead campaign against Lord Browne Chancellor bid2 July 2025 News / Clare students call on College to divest3 July 2025

News / Clare students call on College to divest3 July 2025 Lifestyle / It’s pretty fun to talk to strangers3 July 2025

Lifestyle / It’s pretty fun to talk to strangers3 July 2025 Science / It’s only rocket science, Elon3 July 2025

Science / It’s only rocket science, Elon3 July 2025 News / Join Varsity‘s editorial team this Michaelmas23 June 2025

News / Join Varsity‘s editorial team this Michaelmas23 June 2025