Why are Black students four times less likely to be awarded a First?

Ella Hawes investigates Cambridge’s awarding gap problem and what is being done to close the divide

The University of Cambridge has historically struggled with racial inequity in admissions, but gradual progress has led to record intakes of Black students almost every year for the past decade. But this movement towards equality obscures the disparities in education within the University itself, and more importantly, the chance for Black students to leave with a top grade.

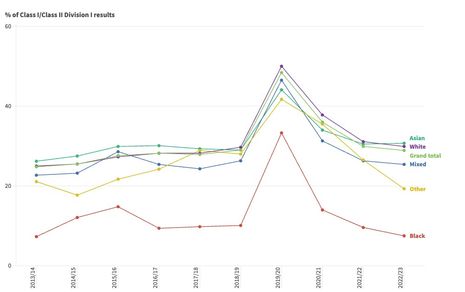

In last year’s results, Black students were nearly four times less likely to be awarded a First than their White or Asian peers across all tripos examinations. According to data seen by Varisty, while around 30% of White and Asian students were given the top grade, only 7.5% of Black students gained a First. Although the gap is most pronounced in the awarding of Firsts, there is also an 18-percentage point gap in the awarding of ‘Good Honours’ (either a 2:1 or a First), potentially placing a serious impediment on the chance of future study or employment after graduation.

All students are admitted to the university with similar predicted outcomes, with top grades from school and the expectation of success at Cambridge, so what is going wrong? Although these figures are some of the worst in recent years, awarding gaps are not a new issue.

"Last year, Black students were nearly four times less likely to be awarded a First than their White or Asian peers"

Back in 2018, the Office for Students (OfS) tasked all universities with studying inequities in the national student body over a five-year period, and found two groups to have unexplained awarding gaps: Black students, and students with mental health conditions. They asked universities to implement an Access and Participation Plan (APP) to analyse data relating to these demographic groups, with the aim of removing the awarding gaps altogether. The Centre for Teaching & Learning at Cambridge set up their APP in 2019 and the project is now in its penultimate year, making this an ideal time for reflection on the progress so far.

The awarding gap for students with mental health conditions has stabilised over the last few years, and there is now only a minimal gap in performance across all students declaring disabilities, with a 5% awarding gap between students declaring mental health conditions and those without any declared disabilities. Pressure has been mounting in recent years over the mental health crisis at Cambridge, and it is likely that the increased provisions for support and exam adjustments have had a knock-on effect on academic outcomes. However, the University’s statistics fail to account for those students who develop mental health difficulties during their studies, potentially skewing the available figures.

While the awarding gap for students with mental health conditions shows improvement, the proportion of Black students awarded Firsts is now at its lowest in nearly a decade, while top results for White and Asian students continue to climb. The APP set out a key objective to “eliminate the unexplained gap […] between White and Black students by 2024-25,” but it seems that ambition is years away from being realised.

"The proportion of Black students awarded Firsts is now at its lowest in nearly a decade"

So, why does the awarding gap continue to grow? Why does the issue persist despite improved access and support? More importantly, what is being done to fix it?

When the APP was initiated, it was a project purely designed to analyse the awarding gaps – rather than fix them. And so the Access and Participation Plan Participatory Research Project (APP PAR) was born. This sister project develops methods of remedying the inequalities within the institution, rather than simply studying them. If the University data is about what is going on, and the APP is about why, the APP PAR is all about how we can fix it.

Although many universities were carrying out their own research, Cambridge took a different tack, hiring students as “paid researchers to do targeted projects as opposed to using them as data sources,” says Dr Ruth Walker, part of the Centre for Teaching & Learning and the project lead of the APP PAR. Rather than being subjects of the research, the students would carry it out themselves, using their own lived experience as Black students at Cambridge to inform their proposals.

The APP PAR runs in yearlong cycles with a fresh intake of student researchers each cycle. One of the first projects carried out was the founding of the Black Advisory Hub, which reaches over a hundred Black students during each year’s induction events, while also running research projects and providing networking opportunities throughout the year. Last year the Hub collaborated with APP PAR again, running the Black Awarding Gaps & Decolonisation Forum, which united students and staff in a series of workshops and panel discussions. They set forward a series of recommendations in their student-led workshops which were endorsed by everyone in attendance, but the difficulty remains in bringing these recommendations to realisation.

"Cambridge’s issues with inequality go far beyond admissions"

Walker remembers that when many universities were told to begin these projects, they all thought that “if we put this investment of time and resources into it, we will solve the problem” but it quickly became clear that the issue is “much more complex and nuanced than many universities actually appreciated, including Cambridge.”

The compilation of hundreds of students’ insights over the last five years only confirms the multifaceted nature of the situation, and that, ultimately, “there is not going to be a silver bullet to solve the awarding gap whether that’s race, disability or gender.” Currently, the APP PAR is focused on implementing smaller-scale projects, with the hope that a gradual and piecemeal approach will lead to real change.

What it comes down to now is time and money; progress on anything at this university is slow. It is likely that the students who have worked on these projects will not see their work come to fruition before their graduation as this work is “beyond the life cycle of any individual student” and so is carried out to “make a difference for future students and not just for themselves.”

Despite the efforts of the students and staff who are working hard to remedy the awarding gap, the numbers remain painfully clear. Cambridge’s issues with inequality go far beyond admissions, and the limitations on Black students’ education will likely continue for years to come.

News / Cambridge students set up encampment calling for Israel divestment6 May 2024

News / Cambridge students set up encampment calling for Israel divestment6 May 2024 News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024 News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024

News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024 Fashion / Class and closeted identities: how do fits fit into our cultures?6 May 2024

Fashion / Class and closeted identities: how do fits fit into our cultures?6 May 2024 Features / Cambridge punters: historians, entertainers or artistes? 7 May 2024

Features / Cambridge punters: historians, entertainers or artistes? 7 May 2024