From quill to grill: Five centuries of Cambridge student dining

Ayushman Mukherjee takes a look back at what we’ve been eating for the past half millennium

French onion soup. Chicken supreme. Bread pudding. If you’re lucky – tea and a cheeseboard. While no doubt a great meal, you’ve probably forked out some £20 for this, and you’re not even half full. As you embark on the walk of shame to Taco Bell (still in your gown, to let the townies know that this isn’t your only dinner), you can’t help but wonder: was Newton also ordering a Volcano Burrito Box on a Thursday morning?

You probably weren’t wondering that, but the answer is no. Student diets, like those of the country at large, have changed dramatically over the years – and their history is one marked with both imperial opulence and readily accepted inequity.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, college halls were still quasi-monastic. As Dr. Rob Payne, archivist at Jesus College, notes that meals began with Grace and Bible readings, and all ensuing conversation was to be strictly conducted in Latin. Food costs were provisioned at 14d a week for Masters and Fellows (approximately £52 today, adjusted for inflation), and 8d a week for students (£30 today). These budgets certainly weren’t shoestring. But in an era of nascent global trade, most ingredients were locally sourced from farmers and markets. Many of the colleges, for instance, sourced their fish and spices from the annual Stourbridge Fair (which was, at one point, Europe’s largest market fair), held in Stourbridge Common in the north of Cambridge from the 12th through to the early 20th centuries.

Such fairs and local distribution networks brought fish as exotic as dogfish, turbot, and stingray to student dinner plates – alongside spices such as saffron, cloves, and mace (a disappointment given that our spice usage now seems to have regressed to salt and pepper). Meat was less common, though it was consumed on occasion. According to Dr. Francois Soyer, an early modern historian at the University of New England, the fellows at King’s spent 40d on swan (£153 today) on the Feast of St Nicholas in 1447. Fish and meats were also typically supplemented with bread and ale, which in 1447 constituted some 35% of the college’s food budget. Count me in.

In the medieval era, dining in hall had been compulsory for all. But by the 17th century, this was no longer the case. This change occurred just as a new eastern import was starting to take the town by storm: coffee. By 1660, Cambridge had spawned its first independent – Kirk’s. And in the 18th century, many more were to follow. These establishments were frequented by fellows and undergraduates alike. They offered chocolate, tea, and sherbet alongside an assortment of newspapers and periodicals. One such establishment, Clapham’s, was described by academics as the 18th-century equivalent of Starbucks (though their house specialty appears to have been calf’s foot jelly, somewhat far removed from a pumpkin spice latte).

The coffeehouses would grow so popular as to become a serious concern for the University's administrators. As one writer in 1742 lamented: “The scholars are so greedy after News (which is none of their business) that they neglect all for it… for who can apply close to a subject with his head full of the din of a Coffee House?” Professors, too, were ensnared – with one German visitor in 1710 finding all the “chief professors and doctors” reading “papers over a cup of coffee and a pipe of tobacco” and “conversing on all subjects”. The University’s hand was forced – and a series of regulations between 1664 and 1750 severely curtailed student patronage of the coffeehouses. Now, if only they could get around to finally regulating Spoons.

"For who can apply close to a subject with his head full of the din of a Coffee House?"

By the 19th century, as the University’s intake began to broaden, a stark divide emerged between its haves and have-nots. Tuition fees at the time were ostensibly progressive. In 1808, noblemen were to pay £10 per term (approximately £26,000/year today, adjusted for the average income), pensioners – referring to a class of students from privilege – were to pay £2 10s per term (£6,500/year today). And sizars – those who would typically finance their fees by undertaking College duties – were to pay 15s per term (£2,000/year today).

However, as Dr Payne notes, those students from privilege often “expected to be offered a higher standard of living,” on account of their greater financial contributions. One particularly illustrative example is that of the “pensioners’ table” in Jesus College. In 1830, pensioners at Jesus petitioned the college to establish exclusive use of some of the tables in Hall - separated from those of the sizars. This was a matter of particular irony, as the words from Psalm 133 “Ecce quam bonum et quam iucundum fratres habitare in unum (Behold how good and how joyful it is for brothers to live together in unity)” are incised in the very same room. Nonetheless, the college acquiesced to this Mean Girls-esque request, and would even establish a special “Hall Fund” to supply the table with linen, crockery, and plates. At least they were generous enough, as Dr Christopher Stray of Swansea University describes, to “let the poor students eat the leftovers of their meals.”

"At least they were generous enough ... to "let the poor students eat the leftovers of their meals""

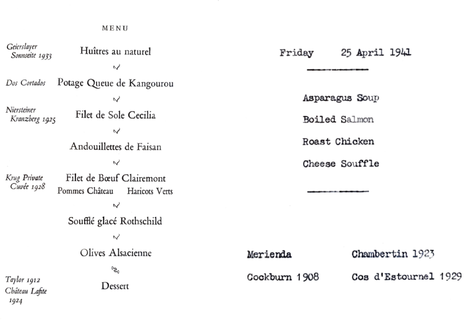

World War II would ultimately prove decisive in ending many of these culinary inequities, principally by bringing everyone to the same lowly level that we have now grown accustomed to. St John’s has produced a particularly detailed account of wartime rationing, but I thought this could be best illustrated through the familiar language of formal menus. These menus have been sourced from the records of an old Cambridge dining club called “The Family”. While it is not known precisely when the club was founded, it was comprised principally of fellows united by Jacobite sympathies – and was certainly active by 1786 (I am unsure as to whether it still exists: the most recent records appear to date from 2001). In any case, their records – which can be found in the University Library – are a treasure trove of menus dating back to the middle of the 19th century.

The consequences of wartime rationing for the historically privileged fellows are clear when one compares a menu from 1939 (left) to a menu from 1941 (right). As a proudly monolingual economist, I would’ve certainly struggled to decode the former. But, armed with Google Translate, it appears as though asparagus soup was used to substitute for kangaroo tail soup, boiled salmon for fillet of sole, roast chicken for pheasant andouillettes, and cheese soufflé for Rothschild soufflé. While rationing ended in Britain in 1954, clearly Hall never got the memo. Menus from the following decades are equally austere, and I could quite easily have mistaken the 1941 menu for one today. If instead I had received the 1939 menu, I would have immediately checked my bank account to make sure I hadn’t accidentally spent £400 on a dining ticket to John’s May Ball (I have).

Does food at Cambridge mirror (as all things seemingly do, according to my 80-year-old supervisor) Britain’s decline? It is perhaps a bit more nuanced than that. Yes, you won’t find kangaroo tail on the menu anymore. But neither are our fellow students left eating our scraps, and that is something we all ought to be glad about.

News / Cambridge students set up encampment calling for Israel divestment6 May 2024

News / Cambridge students set up encampment calling for Israel divestment6 May 2024 News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024 News / Proposed changes to Cambridge exam resits remain stricter than most7 May 2024

News / Proposed changes to Cambridge exam resits remain stricter than most7 May 2024 News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024

News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024 Fashion / Class and closeted identities: how do fits fit into our cultures?6 May 2024

Fashion / Class and closeted identities: how do fits fit into our cultures?6 May 2024