‘A Quiet Night and a Perfect End’: Compline at Cambridge

In the dusky confines of Cambridge’s chapels, the ritual of the “Night Prayer” is evolving, writes Joshua Gleave

In a candlelit chapel, a priest breaks the silence: “The Lord Almighty grant us a quiet night and a perfect end.” The congregation reply: “Amen.” It is around 9.30pm. The service – Compline – has begun.

These opening words have a long history. You can find them on the Church of England’s website or in The Garden of the Soul, a Catholic prayer book from the 1700s. But the practice of Compline, which “completes” the day in prayer, stretches back even further: in the sixth century, it was the nightly custom of Benedictine monks, the last of seven rites they would perform each day. And, since student life was originally modelled on monastic life, Compline has long inhabited Cambridge college chapels too.

The role of Compline in Cambridge life has changed, however. In 1516, a college statute demanded that all members of St John’s College attend Compline every Sunday, every feast day, and every evening before those days; if you were absent, or late, you were fined. Compline seemingly became non-compulsory, but remained regular and popular into the late 19th century; attendance at Selwyn’s daily Compline service was, by one account, “warmly and successfully invited”. Nowadays, though, Compline is a special occasion; my chapel at Corpus Christi only holds the service once a term (if that).

“Compline singers must therefore feel the music freely, alert to one another and to the chapel’s reverberations”

I spoke to Rev’d Arabella Milbank Robinson, Chaplain at Selwyn, about these changes: her answer is to often say or sing the Compline rites privately before bed (or in bed!), keeping Compline’s nightly rhythm between services (which happen twice a term). Perhaps because of its rarity, Compline remains a very popular service at Selwyn, drawing people of “all faiths and no faith”, undergrads, postgrads and fellows.

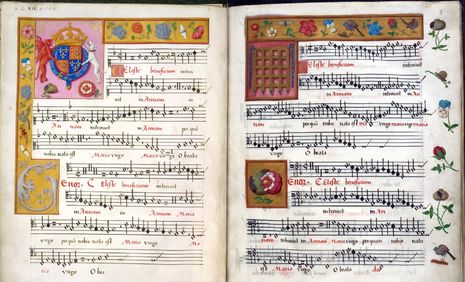

Compline’s unique beauty shines most, for me, in its music. This is music of perhaps the earliest style used by the church: plainchant – unaccompanied vocal music, sung to a single melodic line. For those of us who sing, plainchant takes some getting used to. It is written out in in a now-defunct system called “neumatic notation”, which gives little instruction in terms of rhythm. Compline singers must therefore feel the music freely, alert to one another and to the chapel’s reverberations. Molly Papps, who was choral scholar at Jesus last year, told me about the “calming” effect of this unified choral style: “Plainchant makes me realise how lucky we are to sing in beautiful historic spaces, as during Compline you have to listen to the building as a group to know when to start and stop.” Even if you don’t attend a Compline service, you can listen to a beautiful 1992 recording of one by Clare College Choir on Spotify.

“Compline...is another “answer to those different emotions that the night time brings””

In Anglican churches, congregational hymns are the dominant musical form; it is rare to hear choral plainchant, arguably for good reason. Many feel it is important for worship to build community – this dimension is somewhat lost when so much of the service is enacted only by the choir. On the other hand, Arabella pointed out to me, this alleviates some pressure from non-Christian attendants, who needn’t decide so much whether to verbally or musically participate. The increased role of the choir also opens up space for the priest themself to meditate and pray during the service, she told me. Worship is not just a collective experience, too – it can be an intensely personal one: a priest once told me that we each go to church to “meet our maker”. Compline’s archaic, sublime music suits that encounter well. Selwyn are even considering holding an entire Compline service in Latin, furthering the atmosphere of dramatic, medieval otherness.

In his Regula Sancti Benedicti, a set of rules for monastic life written around the year 530, St Benedict insisted that “after coming out from Compline no one shall be permitted to speak”, on pain of “severe punishment”. If you don’t mind compromising on the full monastic experience, though, I recommend Compline at Jesus: after the service, everyone gathers in the Dean of Chapel’s rooms for hot chocolate or port, restoring the social aspect some might miss in the service itself. In contrast to the austere traditionalism of the service, the atmosphere here is relaxed, and the shelves hold books about John Coltrane. Pembroke similarly runs ‘Compline, Cocktails & Candlelight’, with G&Ts on offer in the antechapel once the service is over.

The night is particularly important to the student experience. Late, when worries and other negative feelings can accrue, students may go out to the club or the bar for some respite. Compline, Arabella suggested, is another “answer to those different emotions that the night time brings”. An answer, I hope, that some readers will find worth listening to.

News / Cambridge students set up encampment calling for Israel divestment6 May 2024

News / Cambridge students set up encampment calling for Israel divestment6 May 2024 News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024 News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024

News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024 Fashion / Class and closeted identities: how do fits fit into our cultures?6 May 2024

Fashion / Class and closeted identities: how do fits fit into our cultures?6 May 2024 Features / Cambridge punters: historians, entertainers or artistes? 7 May 2024

Features / Cambridge punters: historians, entertainers or artistes? 7 May 2024