Don’t try growing up too fast

“Adulthood’s not what I asked for. If I’m honest, I would give it all back,” says Samuel Foo

Child-me must have seemed pretty keen on growing up fast. “You’re a sulky 40-year-old man in the body of a nine-year-old child,” I remember an intrigued parent volunteer quipping at a Sunday School camp. I’m not sure what earned that remark – perhaps some fashionably nihilistic rambles I picked up from some corner of the internet or other – but I probably harboured secret pride upon hearing it, finally gratified that someone had seen me for the old soul I was, adrift in a sea of insipid puerility. Deliverance could not come soon enough.

“If you’re never fully a child, it seems, you can’t really outgrow childhood”

Yet, here I am now, stranded on the wrong side of 21, and still wondering how I got here. Being in a mature college, every day runs the risk of some mildly mind-warping cognitive dissonance. When someone asks if I’m doing a PhD or my second degree; when I feel obliged to explain how I only count as mature because I had to take two years out before uni. At some level there’s still a hardwired instinct, when someone meets me for the first time, to assume they see a dorky, doe-eyed schoolboy, clad in the wrinkled white of old uniforms. Adulthood has come much quicker than I thought.

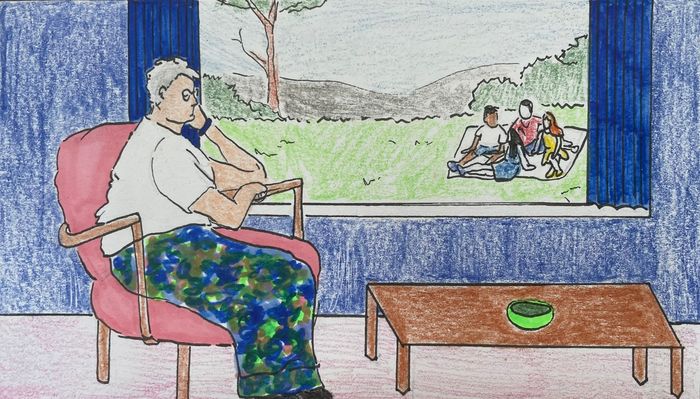

If it’s taking me a while to learn how to be an adult, perhaps it’s precisely because it took me a while to learn how to be a child. I was always craning my neck and tipping my toes to land my precocious grown-up persona a seat at the grown-up table, while my actual child self stayed stunted in its shadow. Clinging to the supposedly ‘mature’ choice of focusing dutifully on academics, I let too many teenage experiences and excesses pass me by. When our value systems keep rewarding children who conduct themselves more like adults than kids, it was an easy mistake to make. I’m paying for it now. If you’re never fully a child, it seems, you can’t really outgrow childhood.

“I wish I’d taken the time to bid my childhood a proper goodbye”

Instead, the closer I’ve come to the oncoming tide of adulthood, the more I feel like I’ve retreated to the ever-receding shoreline of childhood. Over the years, I’ve given up texting in prim professional punctuation for no caps and minimal full stops. Traded my gravelly baritone for a reedy, fragile alto, which in its mellower moments recalls just a shade of the blitheness of boyhood. I used to scorn the kids’ shows my younger sister watched as petty and naïve. Now, while she binges on the usual lineup of adult dramas on Netflix, I turn to old Disney titles and teen shows as a guilty pleasure, seeking out their gentle idealism and youthful freshness as a much-needed refuge from the harsh edges of adult life. Yet, surely all this is nothing but Copium, a futile search for lost time.

I wish I’d taken the time to bid my childhood a proper goodbye. I wish that instead of celebrating rites of passage with such fervour, we paid more attention to the close of each chapter, not every next turn of the page. The mistake I made at prom night – now a distant memory, bitterly separated by two years of conscription (the sort of rite of passage I didn’t want to have) – was expecting that what was to come would be more of the same. It isn’t. Only now, looking back through the radical discontinuity of life abroad, have I come to see how my childhood is well and truly over. I’d known it for a while already, but we can know things without ever realising them.

My only hope is that childhood is perhaps more a state of mind, a mode of being, rather than anything else. Maybe we aren’t all statues in which each new wrinkle is engraved irreversibly by the ruthless chisel of Time: maybe we’re all Russian dolls, with an inner child nestling inside no matter how many layers are stacked on top. Well, you probably didn’t need a degree in folk psychology to have thought of that.

But it has comforted me to think that the treble voice with which I sing has actually been around longer than my speaking voice, even if I don’t use it quite as I did before. It carries all the unconscious threads of muscle memory that connect me, in one line of neurophysical succession, to all the people I used to be. In the same way, it’s comforting to think that my child self has actually been around the longest out of all the versions of me. It’s the one most used to steering the ship, which knows all the things that all these recently-arrived upstarts haven’t the foggiest idea of; which knows, most of all, what it’s truly like to be me. Maybe what I need more than all else, as I slowly emerge into the world that awaits, is not to bid it goodbye, but to let it out and let it be.

News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026

News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026 Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026

Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026 Features / How sweet is the en-suite deal?13 January 2026

Features / How sweet is the en-suite deal?13 January 2026 News / 20 vet organisations sign letter backing Cam vet course13 January 2026

News / 20 vet organisations sign letter backing Cam vet course13 January 2026 Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026