‘C’mon, ref! I’m straighter than that lineout!’

Lewis Thomas talks about heteronormativity, stereotypes, and rugby

I can remember when it all started.

I was in the crowd at a Premiership rugby match (Saracens vs Saints, I think it was), and Saints screwed up a lineout – well, they didn’t so much screw it up as try to rig it, as the ball went hurtling to the left instead of down the middle. Cries of despair went up from the Saracens fans, as we waited to see if the ref called a penalty or reset the lineout.

Somewhere in my mind, a dimly remembered jibe from the secular god that is Nigel Owens came into mind, and I found myself yelling over the crowd: “C’mon, ref! I’m straighter than that lineout!”

I’m gay, and yet I’m straighter than the lineout – geddit? Yeah, it’s a pretty crap joke, but it got a laugh from those who heard it.

It was at this point that the awful realisation hit me. There I was, a self-declared and active homosexual, with a crowd of extremely well muscled (and, in some cases, rather good-looking) men hurtling around in front of me, and I was focussed more on the style of play.

“my being gay counts for nothing apart from whom I want to have intimate relations with"

Then I realised how idiotic a conclusion this was. My sexuality is completely independent of my cultural and sporting pursuits, and I would do well to remember that. But that independence is often forgotten in society, as it all gets subsumed in a mad rush to allot certain attributes to certain sexualities, and to assume sexuality where there is none.

This is mostly an article about heteronormativity – about the way in which society tends to assume heterosexuality in the absence of proof otherwise. But this focus is cut with an anger at the LGBT community, which at times seems hell-bent on assuming a certain experience and forgetting the diversity of thought and experience that makes up the LGBT world.

Heteronormativity is the belief that people are, by default, heterosexual, and that there is a binary divide between genders (‘hetero’ is an Ancient Greek word for difference, and is often taken to mean opposites). So heteronormativity is the assumption of necessary difference, taking it as a given that people should be in relationships with members of the opposite sex. Now, this is a problematic enough assumption in the first place, as it treats other sexual orientations as differing from a sexual norm, but it also creates problems via the attributes it assigns and develops. It fuels the idea that to be straight is to behave a certain way, and that to be LGBT leads to a similar incidence of sexual determinism.

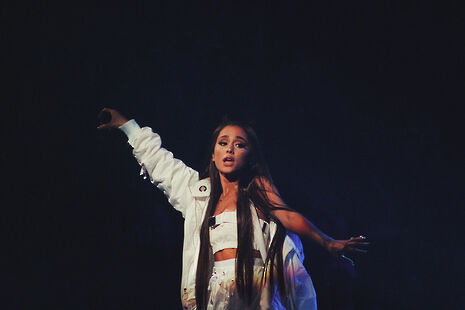

At the risk of sounding reductionist, my being gay counts for nothing apart from whom I want to have intimate relations with. If we rattle through the shibboleths of gay culture in 2017, I don’t like Drag Race, I think Beyoncé is overrated, and the mere mention of Ariana Grande is enough to make me want to either vomit or put on some scream-based punk in order to cleanse my eardrums.

Conversely, I also buy into certain aspects of ‘straight’ culture: I’m a huge rugby fan, I follow West Ham (a team not renowned for their cuddly, socially liberal image), and my music tastes, while diverse and featuring a lot of LGBT+ artists (Against Me!, for example), are not really the sort of thing you hear on the dance floor at Glitterbomb. Culturally, the labels of ‘gay’ and ‘straight’ are all but meaningless, as they seek to assign certain values to an issue which determines nothing apart from one’s sexual preferences.

Being gay has influenced me in numerous ways, but it has bound me in none. My cultural preferences are independent of my sexual ones, and my life experience does not, as one colleague suggested, make me something other than ‘a proper gay’ (whatever that is). I am a proper gay, but not because of the music I listen to, the values which I espouse (ballistically liberal as they are), or the sports I enjoy watching. I’m a proper gay because I’m sexually attracted to other blokes – simple as.

Heteronormativity damages us through its assumption of straightness, but it also damages us through its assumption that there are certain boxes that need to be ticked for a sexual identity to be valid. I know plenty of heterosexuals who fail to fit into a straight stereotype, and plenty of LGBT+ individuals who fail to fall into an LGBT+ stereotype (“are you sure you’re not bi?” “But you like Motörhead?”). By adding a sense of cultural attributes and normality (or lack thereof) to certain sexualities, it strengthens the closets and hampers efforts to make clear just how diverse our society is.

My being gay is normal, just as my heterosexual mates’ being straight is. Some of us fit a stereotype more than others, and others fulfil that stereotype only in whom we are attracted to. So long as we assume sexuality based on attributes other than sexual attraction, we’re going in the wrong direction. So long as we assume that heterosexuality is any more normal than being LGBT+, we’re going in the wrong direction. So long as we hold that being LGBT+ is somehow a deviation from the norm, we’re heading in the wrong direction.

I started this article by referencing a rugby anecdote, and I’ll finish on another one. A couple of years ago, I met Gareth Thomas; when I was a kid, I admired him for the way he destroyed opposing teams, leaving a trail of blood and baffled players in his wake as he steamed down the pitch. Now, I admire him for the way in which, in addition to campaigning for LGBT rights, he has demonstrated that there is nothing that depends on your sexuality. It need not box you in, it should not lead to any assumptions, and it certainly should not limit your expression

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025 Comment / Be mindful of non-students in your societies12 November 2025

Comment / Be mindful of non-students in your societies12 November 2025 News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025

News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025 News / Stolen plate returned to Caius after 115 years12 November 2025

News / Stolen plate returned to Caius after 115 years12 November 2025 Theatre / The sultry illusions and shattered selves of A Streetcar Named Desire13 November 2025

Theatre / The sultry illusions and shattered selves of A Streetcar Named Desire13 November 2025