Why consent workshops are the most important part of Freshers’ Week

Consent workshops at Cambridge are a relatively new phenomenon. Anna Walker looks at their impact

If you are a woman starting university in the UK in 2016, there is a 1 in 3 chance that you will be sexually assaulted before you graduate. I was. If you are attacked, there is 90 per cent chance it will be by a friend, a classmate, someone at college, or someone you know. Would a consent workshop have stopped him from threatening to throw me out his window or for pinning me down on his bed for four hours? Almost certainly not. The courage to attack another student that violently can come only from his confidence that he would never face trial. He was right. A finalist at Cambridge, both of our colleges were inert - there was absolutely nothing they could do.

His college had a responsibility only for his pastoral care, and couldn’t reprimand a student who had not been found guilty in court. Although I had tried to go to the police, the waiting time for a trial in Cambridgeshire was 18 months, and he was due to graduate in a term. I intermitted and flew as far away as I could from the man who had left my body bruised and told me he would ‘destroy’ me. I spent months trying to reclaim my body. He spent less than 24 hours in police custody.

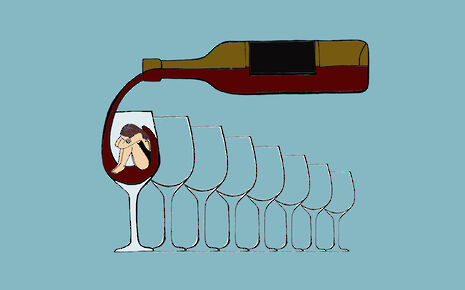

So what’s the value in an hour-long consent workshop in freshers week? The goal is to collaboratively set the culture of the cohort - to agree on what is (un)acceptable behaviour. So many people feel unable to go to the police - marginalised minorities are substantially more likely to be victims of assault, and men and non-binary people who are assaulted are even less likely to report attacks. Consent workshops mutually establish what is and is not acceptable, particularly when navigating consent and alcohol, and cement active, enthusiastic and informed consent as the minimum and the norm. No two consent workshops are the same, because the group decides where the conversation goes. Some points are fairly standard: a passed out person can’t consent, consent is not just the absence of a ‘no’, but an informed and enthusiastic ‘yes’, you need ‘fresh’ consent every time and consent can’t be coerced. The workshops try to debunk popular myths about sexual assault: most rapists don’t ‘look’ like a rapist (jumping out from behind a bush with a knife), a lot of victims of assault don’t fight back violently as self-preservation means that many will ‘freeze,’ and the rate of false allegations is far lower than a lot of people believe.

The number of allegations that are false in the UK is estimated at between 1 - 3 per cent. Although it is concerning that it happens at all, the disproportional focus on false accusations reflects how uncomfortable we still are to talk about sexual assault in Cambridge.

Cambridge is not alone in trying to spark a student-led discussion about sexual assault. CUSU’s Oxford counterpart has been running consent workshops for five years. The US is years ahead of the UK when it comes to talking about sexual assault on campus. George Washington University was the first college to make consent trainings mandatory for all incoming students. The state of Minnesota now mandates that every incoming freshman needs to take a course on campus sexual assault within ten days of starting university.

According to Kathryn Nash, the co-founder of TrainEd, who spoke to The Economist in September, a “high percentage” of assault cases at universities involve first-year students, who often have unprecedented access to alcohol. There should be little doubt that orientations during Freshers’ Week provide the most logical and most effective time for a conversation about consent.

The structure of consent workshops at Cambridge is fantastic because it mirrors the diversity of the college system: peer-led, there is no syllabus or script and any student can volunteer to lead. CUSU Women’s Campaign provides support and training to colleges only if they want it. CUSU also provides help to avoid the feared pitfalls of consent workshops, ensuring that they remain inclusive and acknowledging the wide range of assault victims rather than treating men as potential rapists and women as potential victims. Fears of workshops being ‘patronising’ or ‘accusatory’ are thus generally unfounded.

The autonomy of each college group to lead their own workshops means that each session is a genuine conversation that provides the cohort with a shared set of expectations and vocabulary, rather than a box-ticking exercise. There are also more pragmatic benefits to holding workshops so early in someone’s time at university.

Often, survivors of assault and abuse will share their stories, and might ask for the group to keep an eye out for them when clubbing in freshers’ week. Workshop facilitators frequently lead with questions to nuance the debate: what is the social etiquette in inviting an accused rapist to the same birthday formal as their victim? Is that considered neutrality or complicity? How drunk is too drunk to consent? What is the procedure in college if you are assaulted? Is there anything you can do if you don’t want to report what happened to the police?

There are also more structured programmes available targeting more specific groups. Feedback from one of the Cambridge college’s men’s rugby teams that attended a ‘Good Lad’ workshop was overwhelmingly positive. Although anonymous feedback from one player acknowledged initial concerns that the team had been chosen for the workshop because they had been stereotyped as hyper-masculine troublemakers, these were addressed in the initial exercise, which “dissipate[d]” any “residual awkwardness.” The specific targeting of men in programmes like ‘Good Lad’ leaves it vulnerable to criticism that are harder to direct at the all-inclusive freshers’ week workshops, but open conversation about consent can only be a good thing.

My hope for this year is that we can move beyond debates about whether or not consent workshops are necessary. The number of Cambridge students who are harassed or assaulted each year is reason enough to at least talk about it. It’s too soon to tell whether consent workshops will actually influence people’s behaviour. But it doesn’t cost us anything to have this conversation. Instead of reacting defensively to college consent workshops, help to make them more effective. How can we improve them, quantify and track their successes and impact (or lack thereof), and how can we continue this conversation beyond freshers’ week? We need to deconstruct dichotomies of ‘good men’ and rapists, and acknowledge that our best mates might commit assault. We need to move past the easy targets of the drinking societies and rugby teams, forget the idea that this is an ideological imposition from the Women’s Campaign, and acknowledge the uncomfortable truth that we are all potential victims and perpetrators.

Although not much can change while the conviction rate for sexual assault in the UK is less than 6 per cent, consent workshops can only be a good start.

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025 Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025

Science / Did your ex trip on King’s Parade? The science behind the ‘ick’12 December 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025