Interview: Siana Bangura

Naomi Obeng talks to the Peterhouse graduate who composed a series of viral tweets after being the victim of a racist attack

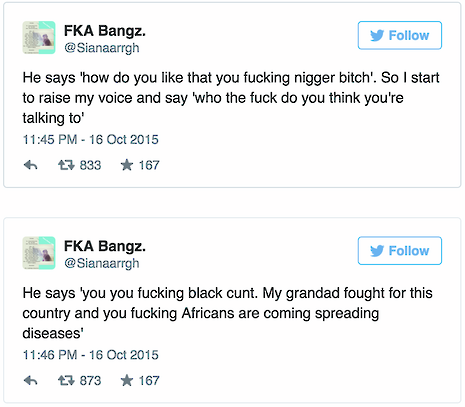

On the evening of Friday 16th October 2015, Siana Bangura was assaulted and racially abused on a train to Liverpool. While stuck at the police station in the aftermath of the attack, making a statement against her attacker and with no internet connection, she reached out to close friends to post a series of tweets describing what had happened. This was “partly so that the people waiting for me at Liverpool John Moore would know why I wasn't on stage performing – I was supposed to be headlining their Black History Month event – and mostly because I wanted people to know what was happening to me in real time: the panic, chaos, confusion, surreal nature of it all.” The Peterhouse alumna, performance poet and founding editor of the movement 'No Fly on the WALL' shared the progression of violence and verbal abuse from a drunken man who was sitting next to her – and the complete inaction of others on the train. It took 45 minutes for anyone to help, even after the man threw a bottle at her.

There was no question in her mind that she should make people aware of the terrible thing she had endured. “I felt exposed and vulnerable and I wanted to emphasise the point that, despite the 'strong black woman' narrative that I perhaps fitted into, I was a human being made of flesh and blood. All I wanted to do was cry on that train, but I refused to crumble in the face of hatred and adversity.”

She never considered editing her story for it to be palatable, despite the brutal reading her experience makes, and this trait is very much rooted within herself. “My priority was to tell it. I speak very plainly. Censoring the language didn't even cross my mind because why should I?” The tweets are shocking, but more-so the reality that they represent, and that was exactly the point.

“If reading such violent hateful racist language upsets you and makes you feel uncomfortable, try being on the receiving end of it - twice.”

It is angering to hear that only a week earlier she had been the victim of another racist attack in a cab. “Nobody made me comfortable or protected me. It is complacency that makes many white people argue racism is no longer a problem when it quite clearly is, especially in places outside of London.”

Consider this: if Bangura had not said anything, how many people who were not on that train would have heard what had happened? Many who have seen her tweets would be complacently unaware that racism is still salient in the UK. Ours is a world in which someone can be made to fear for their life and be told in return, as she recounts in the tweets, to stop making a scene when someone is abusing her. “I wanted people to hear from the victim, because victims of hate crimes and violent crimes are usually silenced by the media and even the law. I wanted to challenge the idea that we are past racism and that these uncivilised incidents only happen in America. I wanted to challenge the complacency, to wake people up and shock them.”

Indeed, the currency of Bangura’s tweets is in their sincerity, powerfully reminding us that we hear about experiences like hers far less often than they occur. “Many were horrified by the racist who attacked me, but every single person was more horrified by the silence of most of the passengers on my train. I think people asked themselves very honestly: 'what would I have done if I was there?' and it is terrifying to tell yourself that you too would have been the silent bystander.”

Aside from the more immediate viral nature of the tweets, she sees an opportunity for people to examine themselves as a result. “One passenger emailed me after seeing the story in the news and taking the time to really read what was going through my mind at the time. He was actually the only person that stepped in to help me. He asked me what he could have done differently. I told him he could have stepped in sooner. I did need more people to stand with me in solidarity. I needed people to tell the racist guy directly that they reject his violence and he is wrong for what he was doing. Instead, I was told to calm down and walk away. Men are rarely held accountable for their actions”.

It would be wrong to suggest that this stems from a British trait of avoiding involvement in the lives of strangers, but one should consider that becoming accustomed to that kind of silence is dangerous. “If you are a dominant privileged member of society, you must recognise that and then be vigilant when people are abusing minorities and vulnerable members of our society.”

She is grateful for the support she has received from across social media, and she is continuing her Black History Month tour of universities, sitting on panels and performing her poetry. “My poems were written to share and be performed far and wide, and I really enjoy meeting new people and visiting new cities.” Her purpose, if anything, has been reinforced. “It has been a real eye-opener so far. What happened to me on the train just confirms that the work I do needs to be done and the things I say need to be said. I'm very excited to keep going and share what I have to say and hear what others have to say too.”

She continues to use her voice and her influence to highlight what is important and often unsaid. Her next endeavour is the Black Cantabs launch in Cambridge at the end of this month: a research project to uncover and promote stories of Black alumni which she co-founded with fellow graduates and current students Njoki Wamai, Eva Namusoke and Nnenda Chinda. In making such waves, she's making strides – her voice is one that we need to hear and her work is work that needs to be done.

News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026

News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026 Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026

Comment / Will the town and gown divide ever truly be resolved?12 January 2026 Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 Lifestyle / The only party girl in the East Midlands12 January 2026

Lifestyle / The only party girl in the East Midlands12 January 2026 News / 20 vet organisations sign letter backing Cam vet course13 January 2026

News / 20 vet organisations sign letter backing Cam vet course13 January 2026