Petar on Film: The Unconvential Rom-Com Part 1

Weekly columnist Petar takes on Amy Schumer’s Trainwreck in the first of his dissections of the latest films

Confession time: I love romantic comedies. What’s more, I refuse to be apologetic about it. I don’t ‘have a soft spot for them’ or consider them ‘guilty pleasures’ (the standard qualifications when you admit to enjoying that Katherine Heigl film). I like their predictability — boy meets girl, boy and girl fall in love, boy and girl live happily ever after (presumably; that part tends to happen post-credits, in my imagination). The rom-com formula is well and truly tried and tested. I find it reassuring and comfortable, like curling up on the sofa with a cosy blanket and a mug of hot chocolate—okay, large glass of red wine—on a chilly autumn evening. Alas, most film critics disagree. These days ‘formulaic’ is the last thing a rom-com wants to be. Cue several recent releases which have experimented with the standard features and structure of the genre, with mixed results. I want to highlight two: Mistress America (the subject of part two) and Trainwreck. One uses the classic conventions of the rom-com to tell a complex story about growing up and navigating the adult world. The other uses the classic conventions of the rom-com to shame women’s choices and preach monogamy as the only viable life path for the modern woman. Let’s start there.

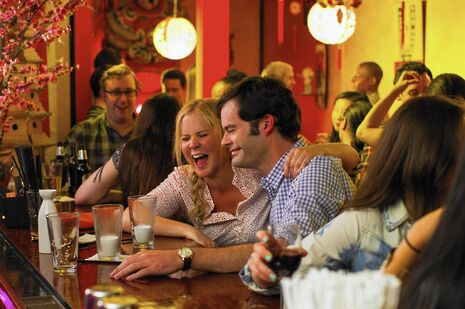

Trainwreck stars Amy Schumer as Amy, a pot-smoking, binge-drinking, casual-sex-having magazine writer. Told at a young age by her father that “monogamy isn’t realistic”, Amy flits from one sexual encounter to the next without any shame or internal conflict. The trailer says she’s “not your typical girl”; the trailer means “she’s not your typical rom-com protagonist”. At work, Amy is tasked with writing an article about a high-profile sports doctor, Aaron - you can guess what happens next. It’s all well-trodden rom-com territory: the romantic montage, the fight, the grand gesture. And it works, of course. It worked in When Harry Met Sally, it worked in 10 Things I Hate About You and it worked in The Proposal. Why wouldn’t it work here?

Here’s why. When Amy and Aaron face their obstacle, as all rom-com pairings are obliged to do, that obstacle is not some screw-up or small misunderstanding: it’s Amy’s character. To get her happy ending, she has to prove to Aaron that she is deserving of him; she has to change. She—not he—must make the grand gesture. Unfortunately, in trying to be progressive by flipping the genders, Trainwreck instead ends up saying something really regressive. That being an independent woman who likes booze and casual sex makes you a train wreck unworthy of happiness (or at least romance). In this way, Trainwreck renders itself more groan-worthily conventional than any traditional rom-com could hope to be.

Amy, who begins the film wanting for nothing, is gradually shown the error of her ways. By the end of the film, she repents, turning her life around in pursuit of a monogamous relationship. “Ladies, even if you think you’re happy single, you’re really not,” the film argues. And because the formula works, we buy it: we swoon at the grand gesture and see how happy Amy is and yeah, okay, maybe single women can’t really be happy. This message is a direct result of the clumsy attempt to tweak the formula. In a standard rom-com, we get the happy ending without the insidious condemnation. We’re told in the trailer that Trainwreck is not “your mother’s romantic comedy”. Would that it was.

News / Clare Hall withdraws busway objections after spending over £66k on lawyers10 November 2025

News / Clare Hall withdraws busway objections after spending over £66k on lawyers10 November 2025 Comment / Be mindful of non-students in your societies12 November 2025

Comment / Be mindful of non-students in your societies12 November 2025 News / Stolen plate returned to Caius after 115 years12 November 2025

News / Stolen plate returned to Caius after 115 years12 November 2025 News / Two pro-Palestine protests held this weekend11 November 2025

News / Two pro-Palestine protests held this weekend11 November 2025 Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025

Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025