Go Set a Watchman, Atticus Finch and the dark side of the Founding Fathers

The controversy surrounding the publication of Harper Lee’s novel strikes at the very heart of the USA’s uncomfortable relationship with its past, writes Tom Wheeldon

It seemed for over half a century that Harper Lee had made a wise decision to plump up her laurels and rest on them, because in To Kill a Mockingbird she had said perfectly everything she wanted to say. Any subsequent novels of hers threatened to disappoint by comparison. So, amidst the volcanic euphoria of readers worldwide upon the announcement of a long-lost sequel’s release, a note of apprehension tempered the excitement – especially because Go Set a Watchman is actually Mockingbird’s raw, unedited antecedent.

It is worth noting that Lee’s 1961 bestseller is not universally adored. Flannery O’Connor – a towering figure in twentieth-century American literature; author of dark, defamiliarising tales of grotesque violence in the decaying old South – famously dismissed Mockingbird as just a "children’s book". Cambridge academic Dr. Ian Patterson similarly disparaged it as a "soggy sentimental liberal novel if ever there was one". But as I wrote in the Cambridge Globalist before the publication of Watchman, such criticism misses the point. Much of it is predicated on the expectation that Mockingbird should fall into the dominant Southern Gothic mode epitomised by the savage, macabre fiction of O’Connor and William Faulkner. Despite its avoidance of direct and explicit violence, I can’t help but think of Mockingbird as similar to the Coen Brothers’ cinematic masterpiece Fargo in the way it portrays the horrors unleashed by humanity’s boundless capacity for barbaric acts – but it pits against this nothing more or less than the might of simple human decency and belief in justice.

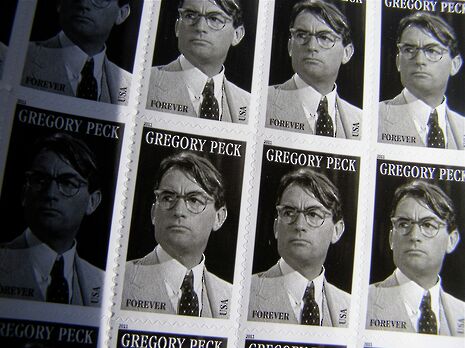

Of course, in the oppressive socio-political climate of the 1930s South, good invariably failed to triumph over evil. That’s why Tommy Robinson is still executed for a crime he didn’t commit, just because of the colour of his skin – and Atticus Finch’s magnificent oratory in the court room could do nothing to defend him. But Watchman is set in the late ’50s, when African-American activists and their allies had started to chip away at the vile edifice of legally enforced oppression. It was thus expected to portray the good man Atticus Finch negotiating the still egregiously troubled but more hopeful climate after such victories as the Montgomery bus boycott.

However, to the shock and dismay of many readers, in the sequel Atticus is a racist. This gives Watchman an extra layer of moral quandaries as seen from the grown-up Scout’s perspective; her narrative voice doesn’t judge a clear demarcation between good and evil as it does in Mockingbird. Hence the novel’s focus on how she responds to the revelation that the kind and loving father we know from reading Mockingbird is also a member of a sinister segregationist group.

In theory, this should make Watchman a masterpiece – a richer, more complex, more adult novel than Mockingbird. But its lack of editorial pruning is all too evident. Despite its use of that simple, well-worn narrative, the trajectory from innocence to experience, Watchman often reads like a loose, baggy collection of anecdotes. Lazy, clichéd phrases abound in its early sections – further limiting the text’s aesthetic power. Twice in three pages, trains are described as moving "like a bat out of hell". Shortly afterwards, Jean Louise (the adult Scout is referred to by her proper name) regards her potential fiancé’s driving skills with "green envy" – a phrase that has epitomised cliché ever since the first person copied Shakespeare’s use of it in Othello, at the start of the 1600s. Similarly, Lee’s crime is not so much casually killing off a beloved character from Mockingbird – it is the jaded, hackneyed language she uses to do so: he "dropped dead in his tracks one day".

But even in the novel’s problematic first third, sentences like "If you didn’t want much, there was plenty" – used to describe Maycomb – are aperçus of the brilliance Lee distilled into Mockingbird. And after that first hundred pages the dialogue begins to sparkle, and acts as a powerful vehicle to express the painful ruptures in private lives as the white powers-that-be launch a rearguard action against the civil rights movement.

Two set-pieces of dialogue – between Jean Louise and Dr. Finch, and even more significantly, between her and Atticus – show Lee’s dexterity in using speech to explore her central preoccupations. The most salient theme she looks at in this manner – little-noted by critics and reviewers so far – is America’s troubled relationship with its Founding Fathers. These men were and are idealised for the Enlightenment values upon which they founded the brave new world of the USA. For many, these values are encapsulated in the Declaration of Independence’s guarantee of "life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness". But these rights were emphatically not granted to African-American slaves, including those owned by Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and numerous other Founding Fathers.

So when Jean Louise confronts her eccentric, intellectual uncle and asks him to explain her father’s involvement in a white supremacist group, it is immensely significant that he responds by referring to "a political philosophy foreign to it being imposed on the South", as well as his "constitutional mistrust of paternalism and government". And it is even more significant that during her argument with Atticus, he defines himself as a "Jeffersonian Democrat". Few figures in American history are more quoted or harked back to more affectionately than Thomas Jefferson. He was a magisterial speaker and writer against the malevolence of autocratic tyranny, and in order to stop the sewing of its seeds in America he extolled the virtues of a non-interventionist federal government that would recognise the powerful self-governing rights of individual states.

This set-up did a lot to foster America’s diversity, its unwavering democracy and the free-market economic dynamism that made it the most powerful nation on earth. But like Jefferson, with his possession of slaves, it had a dark side. The idea of states’ rights was consistently used to support the idea of allowing states to freely oppress African-Americans. This Jeffersonian attempt at justification was highly prominent when people like Atticus Finch railed against the Supreme Court rulings of the late ’50s and legislation such as President Johnson’s landmark 1964 Civil Rights Act.

In this way, the Atticus Finch of Watchman may well constitute the ultimate portrayal of Jefferson and the other Founding Fathers and their legacy – the "original sin" of slavery and oppression, as Barack Obama once put it. Atticus purports to hold up the most exalted human principles, as the Founding Fathers once did; but just like the Founding Fathers, when it comes to attitudes to black people, the hypocrisy is evident, rank and ghastly.

Go Set a Watchman is a significantly weaker novel than To Kill a Mockingbird on literary, aesthetic terms. But thematically it is a much more mature, complex novel – and in Atticus Finch it shows a Jekyll and Hyde figure, just like the men who gave birth to America.

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025

Comment / Anti-trans societies won’t make women safer14 November 2025 News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025

News / Controversial women’s society receives over £13,000 in donations14 November 2025 News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025

News / John’s rakes in £110k in movie moolah14 November 2025 Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025

Fashion / You smell really boring 13 November 2025 Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025

Music / Three underated evensongs you need to visit14 November 2025