Redressing the romantic

It’s easy to be seduced by the events of a narrative, but as readers we need to remain scathing and cynical, says Noa Gendler.

We remind teenage girls all the time that the Twilight Saga is not romantic, and rightly so. It is, after all, the tale of a man stalking a young woman, possessively controlling her friendships, manipulating her into marrying him and then trying to force her to have an abortion when she becomes pregnant. But I think we who criticise Stephanie Meyer’s dangerous Mormon advertisement are privileged by our detachment from pre-teen chick lit in a way that we are not from the twisted narratives that we uphold as ‘high literature’.

An obvious example is Romeo and Juliet. Boy meets girl, they fall madly in love on the spot and get married. Three days later they realise they can’t be together and kill themselves. The poetry of the play is undeniably beautiful, conveying the intensity and craving that is more than likely to accompany the birth of an adolescent obsession. It’s the madness that makes the narrative so compelling: were the two teenagers to flirt quietly like most people do when they fancy each other, it wouldn’t be much of a story. Audiences are engaged by extremity, and that’s why Shakespeare succeeds here.

But it is a testament to his skill that so many throughout the centuries have considered Romeo and Juliet a love story. We are so engrossed by the grandeur, the passion and the peril that we forget what’s really going on: two unstable, lonely kids, brought up in an atmosphere of hatred, lashing out for a moment of autonomy. We might forget that this is the basis for the narrative, substituting the violence of the play with our preferred sentimentality, but I reckon that Shakespeare didn’t; even for a Jacobean audience, a wedding within 24 hours of meeting and a 14-year-old bride would have been considered absurd. I can’t help but read the romance as a dangerous consequence of wilful and foolish behaviour, rather than as a heart-breaking representation of ‘true love’. After all, tragedies are moral tales, and to forget the moral – that “violent delights have violent ends / And in their triumph die, like fire and powder, / Which as they kiss consume” (2.6.9-11) – is to neglect the text itself. As attractive as Leonardo DiCaprio is in the movie (despite the curtain hair), there’s nothing romantic about this story.

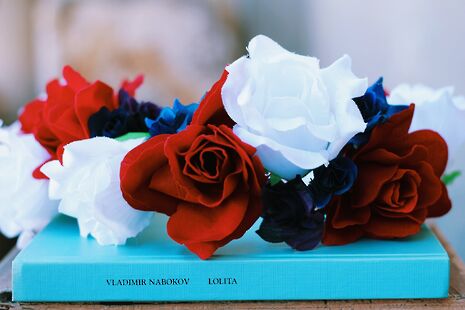

I’ve spoken to a fair number of people who agree with me on that one (including my supervisor – we ranted about it for ten minutes last week). But one on which I’ve heard varying opinions is Lolita. I first read this when I was about sixteen, and I think I fell into the trap that most people fall in. I first read Lolita as the story of a miserable man who couldn’t repress his insatiable sexual appetite for little girls, and hated himself for it. I read the story of a man seduced by a cruel, bratty eleven year old, ashamed of his weakness.

I think this was an immature approach. It’s not nearly as immature as the interpretation put forward by the girl in my Year 13 English class, who said that Humbert Humbert is an evil paedophile and that’s all that Nabokov is saying. But it’s immature nonetheless. Because, obviously, he isn’t an innocent who is seduced by a controlling woman. He is a murderer, kidnapper, and rapist. And, like Shakespeare, who uses veiling language to disguise the mistakes of some silly teenagers as love, Nabokov uses Hum’s apologist, tormented voice to lead us astray. We should be confused by him, to find his narrative compelling, yet repulsive; to pity and despise him; to desire his freedom from his desires and his imprisonment by law. Like Romeo and Juliet, to abandon the complexity and forget to hate Humbert is to misunderstand the narrative. But once again, this is not a romantic story. It’s the story of a paedophile, and I think this is forgotten too often.

Other novels must be treated with the same discernment. Jack Kerouac’s On the Road is so regularly thought of as the adventure of free young men who experiment and go where the wind blows them. But it isn’t. It’s about alcohol and drug addicts who abuse women, can’t support themselves or hold steady jobs, and leave their wives and children for mistaken, fruitless "adventure". Kerouac does a good job at tricking us into forgetting how obscene these characters are, and that’s the point: we’re meant to be seduced by their reckless, flyaway carelessness. But there are reminders throughout that it’s not as romantic as it seems to be on the surface. In Part III, Galatea Dunkel says to Sal of Dean, “he’s got the secret that we're all busting to find out”. But there’s no secret, of course. Dean’s just a shit who only cares about himself, and by the end of the novel Sal’s almost realised this. We need to realise it, too.

If we only look at the glowing exterior of texts we won’t learn from them the messages that they offer. It’s easy to see a glittering love story about a boy and a girl; the tragic descent of a fragile old man; the thrilling, wild adventures of life on the road. But there’s more to all of them than that. It’s a test, so don’t be ensnared like the characters are. These stories, and so many others that we gloss over, are unbelievably fucked up. If we can recognise that and appreciate the skill that went into concocting that complexity, then – in my opinion – we’ve succeeded as readers.

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025 News / Gov declares £31m bus investment for Cambridge8 December 2025

News / Gov declares £31m bus investment for Cambridge8 December 2025 Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025

Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025 News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025

News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025 Lifestyle / Into the groove, out of the club9 December 2025

Lifestyle / Into the groove, out of the club9 December 2025