Film: The Trouble with Adaptations part II

Jamie Rycroft leads us through the decadent, extravagant and questionable interpretations of Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby

After looking last week at Wuthering Heights, a story too long and sprawling to be adapted sufficiently into film, let’s take a look at The Great Gatsby, which is so short, simple and visually vivid that a faithful adaptation can be (and arguably, has been) made. This isn’t to denigrate the book. Despite its modern treatment, as less of a classic novel and more a bundle of symbols to be harvested in English Literature classes, Fitzgerald’s story is still hugely appealing. But its simplicity causes all of the existing cinematic adaptations – the 1949 version with Alan Ladd as Gatsby, the 1974 version starring Robert Redford, and the 2013 version with Leonardo DiCaprio as the lead – to follow the events of the novel, for the most part, very closely.

The main way that these versions are different is the scale at which these events are acted out. Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby, in just over a hundred pages, manages to be two very different stories at once. On the one hand, it’s incredibly public: Gatsby is a Jazz Age celebrity, who hosts huge house parties that draw in hundreds of people. People around him speculate about his mysteriously acquired wealth and fame. Though Gatsby’s decadent actions seem mostly confined to his home in West Egg, the fact that he is friends with the man who fixed the 1919 World Series is a reminder that even his tiniest actions can change the shape of American society. On the other hand, the most important events of the novel don’t take part in the “amusement park” that is Gatsby’s public life, but inside the small, sweltering inner rooms that are his private life. There are only seven characters integral to the plot, and at the heart of the novel is the simplest dramatic paradigm of all: the love triangle. Fitzgerald deftly combined these counter-currents when writing Gatsby, but it’s interesting that in adapting the story, each director favours one of these dimensions over the other.

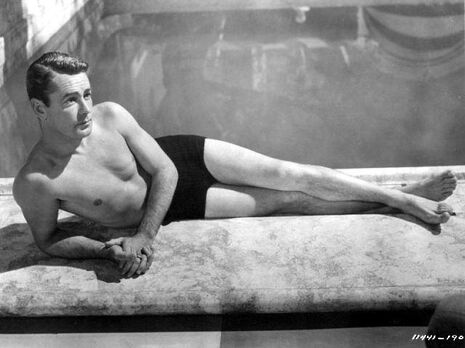

The 1949 version is public, perhaps a little too public. Its production was severely affected by the Hays Code, which wouldn’t allow the film to include the violence and licentiousness of the novel unless it was made explicit that Gatsby was the ‘bad guy’ and not to be pitied. Out went any mystery behind Gatsby’s profession, replaced with montages showing the man as a gangster, with his own “henchmen” and “dark empire”. The result is bizarre: even though it’s the adaptation closest in time to the era that it describes (asides from the 1926 silent movie, sadly lost forever), it seems to be the least faithful to its period. No efforts are made to imitate the costumes or style of the decade. There isn’t even that much jazz, with the studio instead using the song 'There’s a Rainbow ‘Round My Shoulder' to save money. This version can be best described as ‘cheap’, with bog-standard plotting, unimpressive cinematography, and mostly pedestrian acting. It’s a shame that Ladd was saddled with this adaptation, as his portrayal of Gatsby is perhaps the greatest. He is smooth and charming, but fills every action with fragile self-doubt. In his private life, Ladd was very similar to Gatsby, suffering from a troubled personal life and low self-esteem, which likely led to his death from alcoholism. His performance is a glittering jewel amidst an otherwise dull adaptation.

The public elements of the 1974 version, meanwhile, are softer, much like the soft-focus shots used throughout the film. The parties that Gatsby throws look more like wedding receptions than bacchanal revelry (and ironically, look far more fun because of this), and since this film is an hour longer than the 1949 version, the story is faithfully followed at a leisurely pace. Many critics panned this movie for being a by-the-numbers adaptation, and failing to capture the story’s atmosphere, but I don’t particularly agree. It does have atmosphere, but it’s that of the sentimental, romantic moments in the story which many forget. The action is mostly contained indoors, within rooms filled with silverware so shiny that (coupled with the prodigious use of lens flare) everything seems to gleam and glitter. This feels appropriate for Gatsby, a man who polishes away at everything he touches, not to mention at his refined public persona, until it wears away. The acting in this film is equally luminous, and the intimacy of the cinematography allows us to notice inner darkness. Lois Chiles is captivating and seductive as Jordan Baker, Bruce Dern is a delightfully slimy Tom Buchanan, and though I may be alone in believing this, I think Mia Farrow is wonderful as Gatsby’s ineffectual love interest, Daisy. Weirdly, the element that shines the least is Redford as Gatsby. He is adequately mysterious but, under the intensely personal approach this adaptation takes, he is too restrained to convincingly play a tortured, tragic figure. Without delving too much into speculation, a version of this movie with Alan Ladd in the centre would have been something quite spectacular.

And then we have the 2013 version, directed by Baz Luhrmann, a man so fascinated by spectacle that he only ever makes films which are incredible (Strictly Ballroom, Romeo + Juliet) or obnoxious (Moulin Rouge, Australia). Needless to say, Luhrmann goes for the novel’s public aspects, inflating them to nigh-preposterous levels. And yet, it all works to his advantage. Luhrmann was dedicated to making the story relevant to a modern audience, most controversially through his use of an anachronistic pop soundtrack. Yet these anachronisms work where they didn’t work in the 1949 version. The latter tried to awkwardly transpose one period of history onto another which it barely resembled; the former uses modern flourishes to draw connections between two surprisingly similar eras. This Gatsby is as much a symbol of excess in the early 21st century as the early 20th century. Like the Roaring Twenties, our time is defined by a disgusting divide between rich and poor, by hypothetical clandestine factions of wealthy people who buffet themselves against a looming financial crisis. As Jay-Z – quoting Mark Twain – raps in the soundtrack, “history don’t repeat itself, it rhymes”. The bombast is effective, and the occasional moment of subtlety shows Luhrmann to have matured as a director. DiCaprio immerses himself in the role of Gatsby, looking and sounding completely different when playing his public persona. This contrasts well with the rare glimpses we have of his private self. Although the movie has the tendency to over-explain the ambiguous moments of the novel, especially through narration, it surprisingly comes closest to capturing why Gatsby merits the epithet ‘great’.

In terms of choosing which adaptation is ‘best’, it really depends on your opinion of the novel. If you believe it to be a personal drama, then you will likely enjoy the 1974 version most. If, meanwhile, you enjoy being immersed in the story’s extravagance, then you will probably be entranced by the 2013 version. Which interpretation is ‘truer’ to Fitzgerald’s wishes? Neither, really. Which is more important for the story which we live in? The version with Redford is a beautifully honed work, but it’s a reproduction of an era long past. Luhrmann’s vision, though messier, is a living beast: it grabs our present attention and warns us about the future.

Features / Beyond reality checkpoint: local businesses risking being forced out by Cambridge’s tourism industry15 October 2025

Features / Beyond reality checkpoint: local businesses risking being forced out by Cambridge’s tourism industry15 October 2025 Arts / Why Cambridge’s architecture never lives up to the ‘dark academia’ dream 17 October 2025

Arts / Why Cambridge’s architecture never lives up to the ‘dark academia’ dream 17 October 2025 News / How much does your college master earn?17 October 2025

News / How much does your college master earn?17 October 2025 News / Footy captains fury over trans athlete ban17 October 2025

News / Footy captains fury over trans athlete ban17 October 2025 Lifestyle / My third year bucket list17 October 2025

Lifestyle / My third year bucket list17 October 2025