Rise of the televisual

Conrad Landin explores the blurring boundaries between art forms

Much of the wonder and hype – at least in industry and media circles – around Steve McQueen’s historical drama 12 Years a Slave stems from the relief that an art-conscious development with a serious subject matter can be a box-office success. Especially when the studios had stumped up $20 million dollars for a director whose previous endeavours, while definitely successes, were firmly within the realm of British indie.

Film4 was a collaborator, and their role in publicly subsidising independent and often less commercially ‘successful’ films is something which is constantly under scrutiny. This vindication is perhaps Film4's icing on the cake.

More to the point, some have highlighted the fact that McQueen established himself not as a director of television commercials, but as a conceptual artist and winner of the Turner prize for a 1999 video installation. Which might well lead us to ask whether it has been entirely wrong to forecast the creeping destruction of all things artistic in film – in Britain and around the world. There is instead perhaps more space for cross-over between the cinema screens and contemporary art scenes than ever before.

It is certainly true that recent months have seen ‘video installations’ take prime spots in the London art world. Indeed, two come to mind that, like 12 Years a Slave, have themes of race and identity at their core.

John Akomfrah’s The Unfinished Conversation shows at the Tate Britain until March 23rd. A journey through the life of the ‘New Left’ cultural theorist Stuart Hall, it explores narratives of flight, rejection and renewal that are often seen as essential to the Caribbean experience. Three screens in a small inner chamber in the Millbank gallery depict scenes of Jamaica, Oxford and London’s Partisan Café, sometimes simultaneously. They are accompanied by Hall’s TV and radio broadcasts, charting how displacement and circumstance shaped the thinking of one of Britain’s foremost, but oft-forgotten, radicals.

Next month, the Barbican opens a major new show, Momentum, from the London-based studio United Visual Artists. In “a carefully choreographed sequence of light, sound and movement,” we are invited to “explore the installation at [our] own pace.” Such installations are far from a new development: the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall and the Hayward Gallery have played host to many. But as with Akomfrah’s three screens, this guidance displays a conscious attempt to democratise the visual.

Artists still take care to note the ‘sequencing’ of their work – the path of exploration they have in mind during the creative process – but perhaps in doing so they alert us to other options on the table. Such a prospect in mainstream cinema still seems distant.

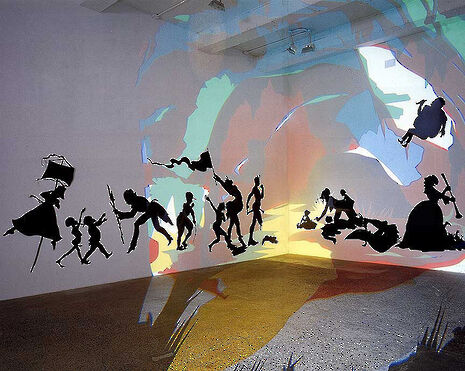

Six miles north, Kara Walker has taken over all three gallery spaces at the Camden Arts Centre. Its title is a sample of what is to come: “We at Camden Arts Centre are Exceedingly Proud to Present an Exhibition of Capable Artworks by the Notable Hand of the Celebrated American, Kara Elizabeth Walker, Negress.”

Whole walls are covered with caricature figures in silhouette, against backdrops which initially appear to resemble the Bavarian woods of Hansel and Gretel. But on looking just slightly more attentively, the tyrannies of race, class and gender in the depictions become clear.

‘Auntie Walker’s Samplers’, as Walker has styled these cut-outs, include acts of horrific sexual and physical violence, and confront the complexities of intersectional oppression head-on. Despite the different angles at which these figures are positioned, there is an undeniable forward movement to the sequence. Suffering is relentless, but this can dangerously be disguised as a necessity of ‘progress’.

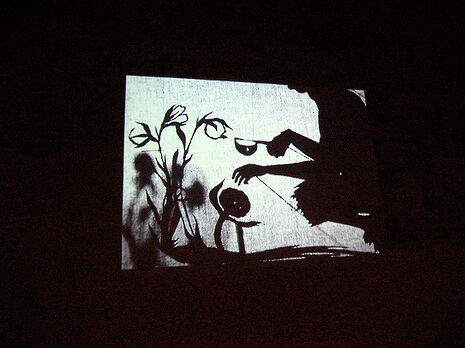

The static movement of the samplers pre-empts the aspect of the exhibition one is likely to come to last of all, a series of ‘shadow-play’ film sequences. These realise the true graphic potential of the violence indicated in the silhouettes. The limitation of shadows allows the artist to go as far as necrophilia and disfigurement. Sexual jerks appear to take over every aspect of movement, as Walker continues her "quest to understand [her] own identity."

Yet, as Marina Warner noted in the London Review of Books, Walker’s work – from “shadow puppets” to “scissorwork” - is a clear echo of the Berliner Lotte Reiniger, who died in 1981. There has always been enough of a blurred line between the arthouse documentary and the video installation for adaptations to cross from one side to the other. Akomfrah’s Tate show started life as The Stuart Hall Project, a documentary for the conventional screen.

That a film like 12 Years a Slave could be seen in a Baltimore multiplex or Cambridge’s very own Arts Picturehouse says a lot for the place of visual art in mainstream culture. As John Berger argued so convincingly in his ground-breaking series Ways of Seeing, the surroundings of art are of huge importance.

McQueen’s film remains the exceptional box-office success, however, and his career’s trajectory remains a conscious decision to move into mainstream feature production. Many creatives in the film industry continue to find they have greater freedom in the production of TV commercials than the producers of Hollywood would allot them on the big screen. It takes a big name – and McQueen is undoubtedly one now, if he was not before – to be allowed to buck this trend. The success of 12 Years A Slave, alongside numerous smaller projects in the art world looking at similar narratives, is refreshing. But it is not that far beyond business as usual.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026

News / Cambridge businesses concerned infrastructure delays will hurt growth5 January 2026 News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026

News / Cambridge academics stand out in King’s 2026 Honours List2 January 2026 News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025

News / AstraZeneca sues for £32 million over faulty construction at Cambridge Campus31 December 2025 Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025

Interviews / You don’t need to peak at Cambridge, says Robin Harding31 December 2025