Poetry Back in Motion

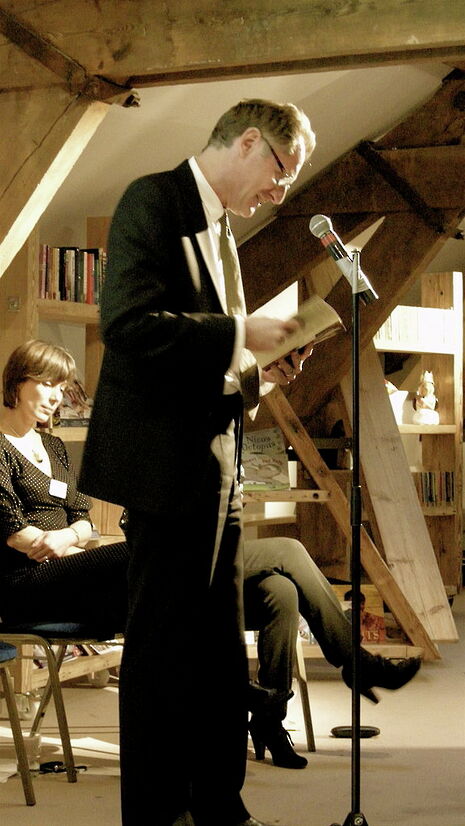

Sir Andrew Motion speaks to Ella Griffiths about his time as poet laureate, his friendship with Philip Larkin and new ways of making poetry accessible to all

Sir Andrew Motion is a man on a mission. As poet laureate, his aim was simple: “To stick up for poetry, to make a conversation about poetry, to make the manifestation of poetry, not just mine, but other people’s, as conspicuous as I possibly could.” All in a day’s work then.

Born in 1952, Motion has been part of this poetic conversation since his time as an English student at Oxford, where he held weekly discussions with W.H. Auden. How was this experience for such a young poet? “He was kindly and looked extraordinary because of that amazingly crumpled face … I’d go and tell my friends that I’d just been having a conversation with God”.

After graduating, Motion applied for a teaching position at the University of Hull, encouraged by the presence of Philip Larkin. The two poets became “proper friends” over a period of nine years, and Motion, as one of Larkin’s literary executors after his death in 1985, would later write Philip Larkin: A Writer’s Life.

What was it like being his friend’s biographer? “I kept reminding myself that if I was writing a book it would be a very big mistake to assume that the Larkin I’d known for the last ten years was the Larkin that existed in previous parts of his life. It was also a big mistake to think that a version of him that he showed me was everything”. Despite Motion’s uncertainty, the book won the 1993 Whitbread Prize for Biography.

I ask whether Larkin was a big influence upon Motion’s own poetry, which shares a similar clarity and sparse style: “Larkin writes poems which, even though they have their complexities and subtleties and nuances, and so on, they are written in a language which is familiar, which is something I’ve always tried to do myself.”

However, Motion cites Edward Thomas as the most prominent inspiration for his own poetry, embracing this “distinct tradition of English pastoral lyric writing.” Indeed, the poet is fascinated by intertextuality: “I don’t have an anxiety of influence, rather the opposite, I have a sort of welcome of influence.”

In his recent collection, The Customs House, this emphasis on dialogue is tangible in the first section that owes much to twentieth-century war poetry: “That was the plan, anyway, partly as a way of creating an immediate historical wind-tunnel for the poems to live in but also because people like me, who have never been on the front line, writing about these extreme and terrifying situations can very easily get caught grandstanding and advertising their sensibility in some rather revolting way.”

Motion succeeded Ted Hughes as Poet Laureate in 1999. Despite finding it rewarding, he has been candid about the effects of the post upon his own writing. Over the decade in the position, Motion wrote about bullying, homelessness, climate change, terrorism and the Iraq invasion.

Was this sequence of commissions a barrier to his creativity? “Yes, it was. And by the end of it I’d had quite enough of it, thank you very much, and couldn’t wait to stop… There’s no question: when I stopped being Laureate I felt energised, I felt like I was a child again, really.”

Instead, Motion focused upon the role’s practical potential: “I decided that the writing bit of the job, which had always been the traditionally expected bit, should really take an equal or even a back foot to the doing bit of it.”

This practical focus included efforts to reform English teaching in schools. Criticising how poems are “routinely used as a means of having a conversation about something else, rather than as an end in itself,” Motion vowed to “put the poetry back into poetry.”

He describes the Poetry Archives, an online collection of audio clips featuring poets reading their own work, as his proudest achievement, hoping to show how “the meaning of a poem consists as much in the noise it makes as it does in the words that we see written down on the page. They are meant to be spoken, enjoyed and not just drearily studied.”

He sees new technologies as a vital tool in this attempt to energise responses to poetry. The internet has created “a much broader spectrum of poetries now than say, forty years ago when I started out. It’s frightening and exciting. I wish we had a crystal ball. I’m sure all publishers wish they had a crystal ball too, because there are extraordinary opportunities opening up for multi-media version of poems, which I can’t wait to happen.”

In 2012 he followed Bill Bryson in becoming president of Campaign to Protect Rural England. Why is saving the countryside so important to him? “It’s for all of us, that’s the whole point. It’s like poetry – it’s for all of us.”

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / SU stops offering student discounts8 January 2026

News / SU stops offering student discounts8 January 2026 Theatre / Camdram publicity needs aquickcamfab11 January 2026

Theatre / Camdram publicity needs aquickcamfab11 January 2026 News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026

News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026 News / Cambridge academic condemns US operation against Maduro as ‘clearly internationally unlawful’10 January 2026

News / Cambridge academic condemns US operation against Maduro as ‘clearly internationally unlawful’10 January 2026