Chick lit or hit?

Charlotte Taylor explores the rebranding of Plath

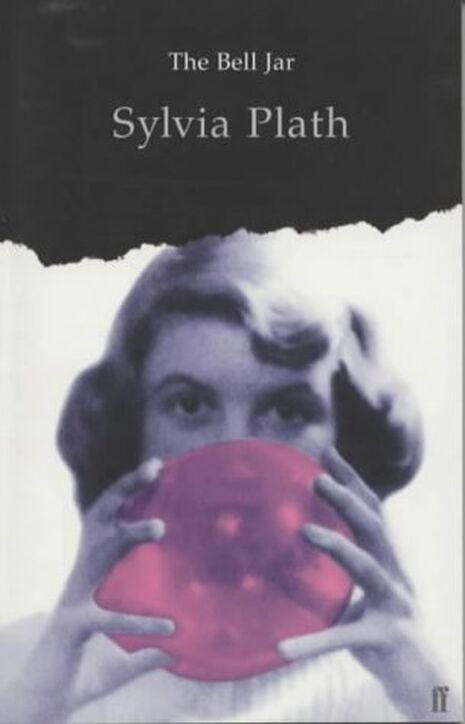

The life and death of Sylvia Plath have always been cloaked in controversy. From her marriage to Ted Hughes, and her suicide at age 30, Plath has always been able to shock and stir the emotions of her public. But her work has always been more scandalous than her celebrity. The Bell Jar, which celebrated its 50th anniversary in January, is her most controversial work due to its stark depictions of modern psychiatric care and female sexuality in a repressive society. So, it is entirely consistent that this work should cause controversy this week, with accusations that Faber’s 50th Anniversary cover art for the novel is reminiscent of ‘Chick lit’ rather than ‘serious’ literature.

It is certainly hard to view Plath’s work as typical of the ‘chick lit’ genre. The tale of Esther Greenwood’s gradual loss of sanity upon entering a world of work, parties and hedonism is perhaps one Cambridge students are familiar with, but could hardly be classed in the same category as a Cecelia Ahern or Jilly Cooper novel.

However, I have taken little issue with the much derided-cover art; in fact, I believe it rather neatly sums up the message of the novel which is about the potency of female social norms, and the potential damage that can be done to the individual. What I found to be of interest in this debate was the derogatory use of the term ‘chick lit’.

The critics laid bare all the supposed obscenities of the genre in response to this cover art: it limits female ambition; it is anti-feminist and so on and so forth. Few critics noticed the subtle misogyny in these seemingly forward thinking reactions. Chick lit is derided due to the plots of its stories, which are frequently romantic relationships and female friendships: In short, the lives and interests of women. In this sense, Sylvia Plath is queen of chick lit. Her work puts the female subject to the fore as much as any Mills and Boon as well as their hopes and desires.

Chick lit, unlike its critics, suggests that the lives and lifestyle of women is as worthy of glorification as the lives of great generals, monarchs and, most importantly, men. Those who deride the chick lit market are actually deriding the lives of women. Esther Greenwood would probably laugh at the controversy. Perhaps her tale deals with more shocking issues, but it is nonetheless an illustration of a woman trying to establish her identity against the world.

Conversely, the queen of chick lit, Jane Austen, celebrated her 200th anniversary of Pride and Prejudice in January to much critical acclaim. Her portrayal of the lives and loves of her characters was applauded for its cleverness and much-loved heroines. Few would claim Austen was limiting female readers for having all her novels end in the marriage of her heroine to a wealthy handsome suitor. Chick lit may be seen in this light as the ultimate symbol of progressive, and Plath’s work is clearly worthy of the label.

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026

News / Right-wing billionaire Peter Thiel gives ‘antichrist’ lecture in Cambridge6 February 2026 News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026

News / Cambridge students uncover possible execution pit9 February 2026 News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026

News / Epstein contacted Cambridge academics about research funding6 February 2026 News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026

News / Man pleads guility to arson at Catz8 February 2026 News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026

News / John’s duped into £10m overspend6 February 2026