Storybook world of bodies: modern ballet

After the appointment of Liam Scarlett as the first artist in residence of the Royal Ballet, Isabella Cookson considers contemporary ballet as technology, questioning its social relevance

We inhabit aspects infused with language. Our sensual encounters with the world are inevitably interpenetrated by the streams of words that flow around our minds and through our mouths. We see someone and they become the evaluative judgements that pop into our heads about them; we walk down the street and flip out into unreal worlds constituted by imaginings and internal dialogues. Languages are a second world superimposed on and intertwined with the physical and emotional worlds. Words are traced in the sky, trapped beneath the stones and smeared across the faces of the people we love. A storybook world in which the word is flesh and dwells among us.”

David Gamez, What We Can Never Know.

At the beginning of this month, the Royal Ballet announced that Liam Scarlett would be their first artist in residence. New, innovative choreography is not something that people relate to ballet. For many it remains either a childhood dream to be a fairy or an interest reserved for posh people. Ballet should be neither, and mostly isn’t.

The critics of dance rarely help this situation. The common discourse that surrounds this art form can feel pretentious and alienating. Reading ballet reviews can feel at times like wine tasting at a Cambridge college: an outpouring of adjectives like “velvety smooth” interjected by French technical terms. To many, it perpetuates the image of ballet as meaningless and irrelevant, but such langauge does not describe what ballet really does, what moves it beyond aesthetic appreciation and into something that can really speak. Capturing dance in language is hard and so we reduce it to something formulaic. But ballet speaks for itself.

Ballet imagines a new kind of language; it is both a preconceived form, with rules and strict techniques and yet one that evolves, adapts, shifts. It is no coincidence that modern ballet looks to technology as a thematic and stylistic inspiration. Wayne McGregor’s piece Infra places a film installation above the dancers below. It shows electronic, faceless stick people casually strolling across the screen, perhaps with a briefcase in hand or wearing a pair of heels. The effect is a cross between Eadweard Muybridge’s Victorian repetitive photographic studies and Lowry’s stickmen: it strips human movement to simple symbols. Below the Royal Ballet dance to Max Richter’s rich composition: mixing electronica with a string quartet. The music and the two images, the dancers on stage and the electronic images above, are not contrasting but complimentary. The plain black and white costumes aesthetically draw this link between the two. In some ways the electronic images simplify the jutting angles and intertwining movements performed on the stage. There is no narrative in this piece but the language the dancers formulate is interpenetrated by recognisable gestures, such as a kiss. Human movement expresses itself by merging movement of everyday experience and movement that stretches the imagination. It is in this paradox between tradition and innovation that ballet is at its best.

This is not merely a new ‘trend’ in ballet- rather it reflects the nature of the dance form itself. Ballet has always relied upon technology: the pointe shoe is, after all, its most signature tool and was first used in the early nineteenth century. Indeed, the process of ‘creative destruction’ that for many epitomises the process of modernisation is microcosmically formed on the body of the dancer. The nerve endings of a ballet dancer’s foot are often damaged; bleeding, blistering feet are the norm for most ballerinas. The previous director of the New York Ballet, George Balanchine, apparently encouraged the dancers to gain bunions in order to create a smoother line from the ankle to the toes. The body is shaped by technology.

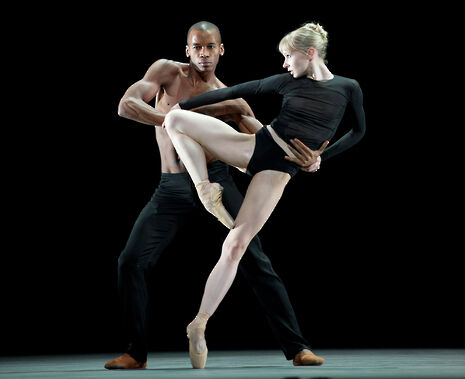

Perhaps a more obvious point is that these bodies are tools themselves. Technology is not its antithesis, rather ballet is a technology: a creative, innovative form of movement that challenges norms and creates. Modern ballets, especially abstract ballets, play with the dynamic between the dancer as an autonomous actor on the stage and dancers as interchangeable machines, cogs in the wheels of a larger body of dance that acts as a collective expression.

Liam Scarlett’s latest piece plays with this: the simplicity of the costumes and the concentration upon patterns renders the piece provocatively impersonal. The focus on the complex footwork is the mechanism through which the dancers express collectively.

The new choreography at the Royal Ballet is certainly innovative. It points to the fact that as a technology, it does not exist within the ahistorical vacuum that its use of fairytale narratives would sometimes suggest. Rather, ballet responds.

But ballet could respond more. There have been no female choreographers commissioned to create for over a decade. And while its productions of abstract ballet have been most interesting, it rarely produces narrative ballets that stray away from fairytale stories or nineteenth-century tales of prostitution. Sex trafficking is indeed an issue today, and people may not die of consumption as regularly as they used to but they certainly do die of AIDs. It is not that they need to be social commentaries, but ballets will not penetrate the imagination in uncomfortable ways unless they locate human struggles within a contemporary context that implicate its audience rather than placating it. It is not that the story of Swan Lake should not be danced; like any technology, though, ballet could at times place itself more closely in the world that surrounds it.

The Royal Ballet’s new abstract choreography, on the other hand, shows promising signs. The new pieces by Christopher Wheeldon, Wayne McGregor and Liam Scarlett have shown that ballet as is building upon and stretching beyond its heritage. Kenneth Macmillan need not be the golden age of choreography at the Royal Ballet.

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026

News / Report suggests Cambridge the hardest place to get a first in the country23 January 2026 Comment / Cambridge has already become complacent on class23 January 2026

Comment / Cambridge has already become complacent on class23 January 2026 News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026

News / Reform candidate retracts claim of being Cambridge alum 26 January 2026 Comment / Gardies and Harvey’s are not the first, and they won’t be the last23 January 2026

Comment / Gardies and Harvey’s are not the first, and they won’t be the last23 January 2026 News / Students condemn ‘insidious’ Israel trip23 January 2026

News / Students condemn ‘insidious’ Israel trip23 January 2026