Exhibition: Snow Country Woodcuts of the Japanese Winter

A new exhibition of Japanese woodcuts at the Fitz takes Lavinia Puccetti to a strange and beautiful world of snow

When opening the doors of the Shiba Gallery at the Fitzwilliam Museum, the feeling is that of having entered a self-contained world which is proportioned, in its scale, to the dimensions of the woodcut prints that the exhibition, Snow Country Woodcuts of the Japanese Winter, displays. This effect heightens and concentrates the attention of the viewer, who is encouraged to look at each single detail represented in the prints – avoiding the daunting effect of a huge exhibition which could easily have ended as an exercise of label checking rather than an act of looking and engagement with the artwork.

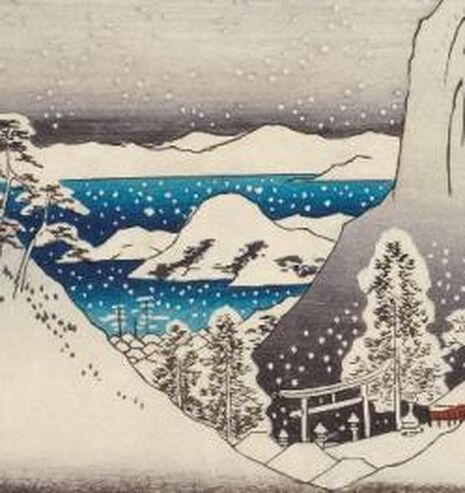

The impression is of having opened a window onto a Japanese winter landscape and culture. The prints are arranged as if to recreate a microcosm: the lights at the top of the displays not only illuminate the artworks but also create a mood within the exhibition: the light is suffused, yet crystalline, evoking the flattened snow ridges seen in the background of Hiroshige’s print, Mount Yuka in Bizen Province.

The series Snow and Music includes Utagawa Kuniyasu’s print dramatising the scene of two Kabuki actors, Kikunojo V and Mitsugero III. The chain unleashed by the warrior on the right continues in the profile of the roof, linking the two figures. The blue and ochre of their garments, along with the night blue of the house in the background, contrasts with the pure white of the snow which covers the scene.

The artist seems to have been more interested in freezing a moment in time, than in depicting the final triumph of one of the warriors. In this print the drama is heightened by the way in which the white pigment has been flicked across the paper, almost obliterating the view of the scene. This has a parallel in contemporary Japanese theatre fights, which were stylised and complemented with languorous music whilst ‘snow’ increased the wintry ambience: the stage covered in strips of white cloth which simulated the weather.

This technique, paralleled in the print by the white pigments dots, recalls the 2012 ENO production of Madame Butterfly: the fall of cherry blossom petals added drama to the end of the first act, when Cio-Cio San sings a love duet with Pinkerton before their first night together. This instinctive association of snowflakes with cherry blossoms is exploited by Tagawa Shigenobu II’s Number 5-Silver colour print.

The scene, from the series An Array of Excellent Horses, depicts a geisha leaning on the balcony of a teahouse, overlooking the Edo Bay at Shinagawa during a winter afternoon. Shinagawa was famous for its cherry blossoms – as well as for being an

unlicensed pleasure quarter where geisha were free to offer their services. They would signal their availability by holding a wad of tissues, or, by showing their naked ankle, as can be observed in this print. Snow is depicted like blossoms on the trees, embossed into the surface of the paper without ink.

The poet Hinanoya Haruko offers a visual comment on this print, associating geisha with snow: “are these other streetwalkers/ floating down along streams/ formed by the melting of snow?” It is interesting to note that the status of prostitution has not been morally condemned in these coloured prints, but rather treated as a natural part of the teahouse culture, to the point of being parallel to natural elements: snowflakes and cherry blossoms. In the same way in which the candid surface of snow reflects light – differentiating it in a spectrum of colours – the exhibition offers images of a variety of realities, which are “interpreted through the main theme of snow”.

They relate deeply to contemporary Japanese culture, in terms of history, theatrical staging, poetry, mythology, gender and social realities. The viewer may struggle to arrive at the true meaning of each print – but a familiarity with the images can be acquired by the simple, patient act of looking at prints such as those exhibited in the Shiba Gallery.

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026

News / King’s faces backlash over formal ticket policy 7 March 2026 News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026

News / School of Biological Sciences will no longer oversee Vet School improvement6 March 2026 News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026

News / Academics push to introduce Palestine studies to Cambridge6 March 2026 Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026

Theatre / Alien Breakdown Play is a promising extraterrestrial experiment 8 March 2026 Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026

Arts / From pupil to poet6 March 2026