Everyday art: The Banknote

Sonia Tong looks at the evolution of paper money and how we interact with it as an object

Paper money evolved from the promissory notes and receipts used to represent coins when its quantity became too great (or, indeed, too heavy) to carry around; eventually these became the medium of exchange in themselves, their worth no longer determined by gold reserves but rather by an idea of a country’s economy in relation to the rest of the world. What is remarkable is that as the actual value of money decreased, its representative power and symbolic treatment increased. Its design became more complex as people realised that it is easier to attach a sense of worth to something tangible, with physical and tactile appeal - that the banknote should be distinguishable from ordinary paper.

The distinct texture, feel and wearing pattern of the paper used comes from its blend of cotton and linen, run through with a metallic thread. The design itself is composed of fine line hatching patterns and micro lettering that cannot be seen at the low resolution of standard printers, which are printed onto the paper using a process called Intaglio, where ink in the grooves of a hand-etched steel plate is pressed onto paper at a high pressure that raises its surface. The watermark, hologram and invisible ink are printed on using a variety of other printing techniques. These features are security measures, of course, but they are also visual symbols of reassurance telling us that our money is unique, safe, and difficult to replicate.

Even when we are not looking at these symbols, we still sense them unconsciously: rubbing a note between our fingers is an everyday ritual. This quality of paper money is universal; however, the banknote is not an apolitical object. Indeed it is instrumental in identifying the country to which it belongs. Banknotes typically depict a person, a landscape or an animal (even this is a security measure, as it is easier to detect discrepancies in a recognisable image) although which particular image is chosen can be revealing of a society. For example, while many countries’s notes including the United Kingdom show historical figures from varying disciplines, America’s are fronted by Presidents, Congressmen and military leaders, whilst China’s predominantly feature the face of Mao Zedong.

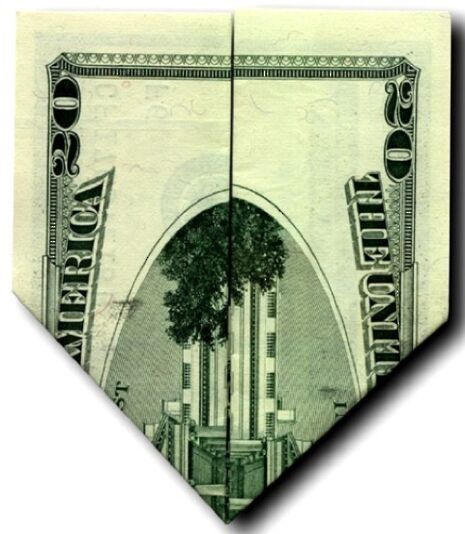

Regardless of the truths and conspiracy theories surrounding these images (famously, the $20 bill can be folded so that it shows the twin towers in flames), they exist – along with flags – as some of the last official visual identifications of national identity. Where a common currency is used between different countries, this both reflects and perpetuates the commonality of their identities. And where different currencies are used, the effect is less alienating than it used to be when travellers had to physically go to bureaus de change and acquire strange looking money. Now with the rise of online banking and e-commerce, it is increasingly easy to use money digitally across the world. With instantly accessible and transferable funds because of services like Twitpay and Pingit, it seems widely accepted that the future of money is electronic.

Yet with this digitalisation, something will be lost. The problem with the dematerialisation of currency is that money will lose a large part of whatever substance it can be said to have, becoming easier to spend and less important to save. The tactile quality of the banknote that stirs memories and desires, symbolises the pride and failures of a country, will disappear along with its unique visual language and iconography..It is not totally unimaginable that in the near future salvaged banknotes might decorate gallery walls, bizarrely representing the abstract relationship between the value of the note and the value of money: as art, it could be worth a hundred times its printed denomination, but as paper it is becoming a bygone scrap of litter in a digital world.

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025

News / Pembroke to convert listed office building into accom9 December 2025 Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025

Features / Searching for community in queer Cambridge10 December 2025 News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025

News / Uni redundancy consultation ‘falls short of legal duties’, unions say6 December 2025 News / Gov declares £31m bus investment for Cambridge8 December 2025

News / Gov declares £31m bus investment for Cambridge8 December 2025