Thinking outside the box

Jack Belloli talks to the directors of The Music Box

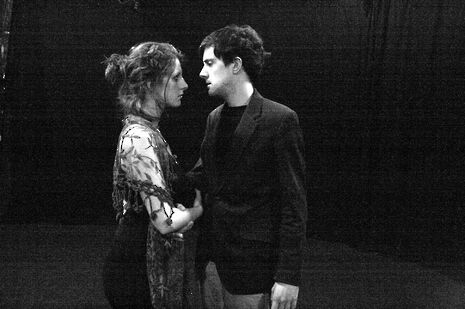

As a theatre critic, you have to do a double-take when the directors you’re talking to admit that they don’t consider their work “a play” – at least not in what they describe as “the nineteenth-century sense” of telling their audience a story. For all that, ‘playful’ seems to be the best word for The Music Box: by turning the Corpus Playroom into a child’s bedroom, it’ll create a space in which to take some exciting theatrical risks.

It all began, conventionally enough, from the script. The play’s first act won its writer, Emma Stirling, the inaugural Florence Staniforth Prize for creative writing last year. Stirling says that it arose from the desire to write about “what it would be like if you were stuck in a room” permanently – but it developed in such a way that the three main characters are caught in an unclear position between childhood and adulthood, and the remaining three characters never speak. More than many others, this play will become something very different in performance – and Stirling is looking forward to the transformation.

Her directing partner, Sophie Seita, is making her first venture into theatre in Cambridge, having worked with a professional theatre company in Germany last summer. The process began by looking closely at the text and its dramaturgy: Seita discusses the Stanislavskian attention to motive and obstacle that she explored in Germany.

From there, a range of collaborators have been sought to flesh out the play: choreography, inspired by the work of Pina Bausch, will offer a window into the characters’ desires; artist Anna Moser is providing the crucial portrait that one of the characters paints over the course of the play; Rhodri Kasim will be playing live music throughout.

There’s something thrillingly risky and sketchy about these contributions: Kasim’s music is improvised, so the actors will respond to something slightly different every night; Moser’s background is primarily in abstract painting, and her portrait will hopefully have the unnerving, impressionistic quality of the puppets the characters play with.

When I ask about what’ll follow from this project, Stirling and Seita reveal even grander plans. They hope to restage the play, in a festival context, on a loop, so that the audience can come and go at any point – doing away with the narrative business of beginnings, middles and ends to make the play resemble the tune of a music box. If all goes well, this production might just run, and run, and run, and run...

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024

News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024

Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024 Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024

Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024