Sense of an Ending for the Booker?

The controversy surrounding this year’s Man Booker winner has aroused many questions, but Charlotte Keith wonders whether they are the wrong ones

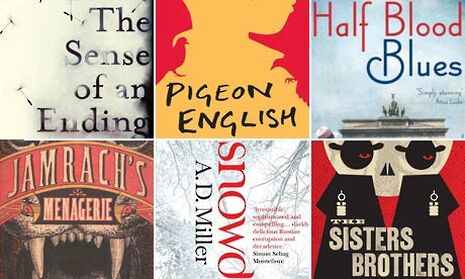

It felt like it had been a long wait. But finally, after only 31 minutes of debate, the judges came to a unanimous decision: Julian Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending triumphed in this year’s Booker Prize. This, however, was only the final act in a year where the Booker has been dogged by controversy and criticism.

First under fire was the choice of thriller writer Stella Rimington as chair of the judging panel. A number of literary noses were turned up in disgust. Judge Chris Mullin’s comment that a book has to ‘zip along’ in order to merit consideration as a winner did not go down well. Accusations of ‘dumbing down’ abounded. Andrew Motion accused the judges of creating a false divide between ‘high literature’ and readability: ‘as if they are somehow in opposition to one another, which is patently not true’. The author Jackie Kay reflected that, ‘it’s a sad day when even the Booker is afraid to be bookish’. In response, Rimington argued that ‘we want people to buy and read these books, not buy and admire them’. She didn’t seem to have countenanced the possibility that reading and admiring are not mutually exclusive.

This ‘dumbing down’ of the Booker has prompted leading members of the literary establishment – a group of agents, publishers and writers, including former Booker winners John Banville and Pat Barker – to launch a new prize, to recognise novels which are ‘unsurpassed in their quality and ambition’. This new prize would not – as the Booker has been accused of doing – privilege readability over artistic achievement; excellence would be the only criterion for success. One publisher, speaking off the record in the Guardian, admitted – ‘it needs to be an utter snobfest’.

The debate about the value of literary prizes themselves has been re-opened – ‘isn’t it ridiculous to make art into a competition?’ – ‘don’t prizes reduce literature to the level of a commodity, seeking only to increase sales?’. But the truth is that, for all their inherent absurdity, literary prizes are a ‘good thing’ in encouraging people to read, maintaining the cultural capital of ‘Literature-with-a-capital-L’, and giving a platform to brilliant novels that would not otherwise get noticed. There is no point whining about the ‘commodification of literature’. Books have been a commodity since the rise of the printing press, since people started writing for a living. It is in their status as public commodities that novels are valuable. The basic premise of the novel form was– and hopefully still is – that anyone who could read, could read a novel. The current distinction between ‘literary’ and ‘genre’ fiction is artificial and unhelpful – and the idea that a prize like the Booker should reward primarily the former seems increasingly unjustifiable.

Ali Smith’s most recent novel There But for The has become the cause célèbre of this debate, with a number of voices weighing in to complain about her exclusion from the longlist. Perhaps, some suggested, it was because her book was ‘too clever’. Well, it is – too smug, too in love with its own cleverness to do anything other than irritate. The irony is that, reviewing both Barnes and Smith, I was struck by their similarities. They are both, after all, contemporary ‘literary’ novelists, and suffer from the afflictions peculiar to this position: affectation, a misplaced belief in their own profundity, a tendency to patronize the reader.

It’s not ‘dumbing down’ that’s the problem – it’s the very idea of ‘literary fiction’. Rimington said of Barnes’ novel that ‘it has the markings of a classic of English literature’. Yes: a classic as defined in the narrowest sense of the term by the current literary establishment. If anything, Barnes was a surprisingly conservative choice of winner for a year supposedly so controversial. What critics of the prize were really objecting to, it seems, was the presence of novels on the shortlist that don’t conform to the expectations of ‘literary fiction’ – thrillers, a Western, a historical adventure novel featuring dragons.

In Whatever Happened to Modernism, Professor Gabriel Josipovici wrote that ‘reading Barnes…leaves me feeling that I and the world have been made smaller and meaner’. I’m afraid I have to agree. But don’t take his – or my – word for it. Who are critics to tell a reader what’s good and what isn’t? If nothing else, this year’s Booker has generated heated debate, and made a talking point of all things literary – and for that, I can even forgive Barnes his musings on why crinkle-cut chips aren’t cut by hand anymore.

News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026

News / Local business in trademark battle with Uni over use of ‘Cambridge’17 January 2026 Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026

Comment / The (Dys)functions of student politics at Cambridge19 January 2026 News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026

News / Cambridge bus strikes continue into new year16 January 2026 Comment / Fine, you’re more stressed than I am – you win?18 January 2026

Comment / Fine, you’re more stressed than I am – you win?18 January 2026 Features / Exploring Cambridge’s past, present, and future18 January 2026

Features / Exploring Cambridge’s past, present, and future18 January 2026