Question Time on Art Crime

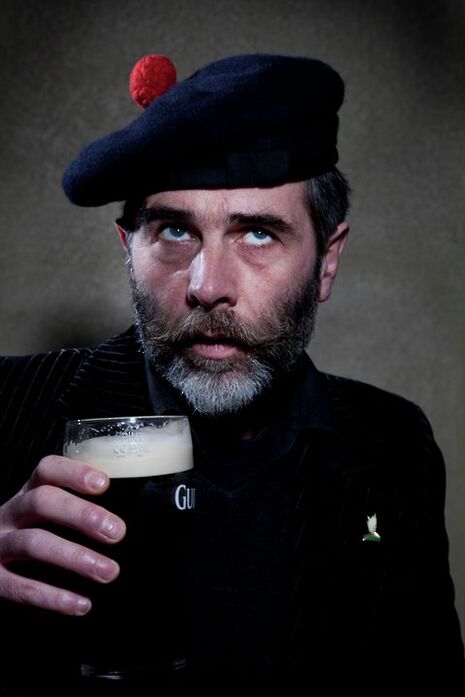

As the Association for Research into Crimes against Art (ARCA), established by Cambridge alumnus, Noah Charney, begins the third cycle of its corresponding Master’s course, Lizzie Homersham asks David Fryer for an artist’s view on how crime really manifests itself in the contemporary art world

Maintaining a sense of perspective in the art world appears to be one of Fryer’s main preoccupations: when I met him for the first time he had been entrusted with the installation of Robert Montgomery’s ‘recycled sunlight’ piece at ArtParis 2010 (an international art fair held in Paris’s Grand Palais). In spite of the imminence of the fair’s opening and the collector’s private view, David seemed somehow outside of time pressures; his careful treatment of the work definitely prioritized over commercial demands and distractions. Fryer’s priorities seemed telling indeed, as the commercialization of art may indirectly be linked - through the art market and the fetishization of works - to increased incidences of art crime, our topic of discussion arising from the ARCA’s idea of combining the study of art history with the study of art crime.

Presented with the idea that 'international gangs use art works effectively as a form of currency', Fryer stated that the secondary art market, often dominated by large businesses, should ‘take a lot of blame for the works being stolen as it tends to emphasize the importance of collections for their monetary, rather than artistic value.’ Stealing is a slippery notion in the art world however. In Fryer’s words ‘vandalism is a recognized form of art practice; theft has yet to obtain such status.’ He illustrated the acceptance of the former with reference to Jake and Dinos Chapman, who have successfully moved beyond the limits of iconoclasm: ‘The Chapman Brothers defaced Goya’s prints The Disasters of war in order to produce The Rape of Creativity. In doing so they reinterpreted original meaning with contemporary commentary.’ An instance such as this does much to validate Fryer’s opinion that the study of art crime would only be interesting to him if the course avoided adopting a uniquely protectionist stance.

Because perhaps the notion of protection, not only applying to theft prevention and defacement but also extending to the habitual interdiction of the public to touch, is one undergoing increasing change. If we look to the Tate Modern’s exhibition of Gabriel Orozco’s work we see the once strictly maintained distance between work and spectator radically diminished. Fryer commented on this approvingly, citing works such as Empty Shoe Box as active encouragement of audience interaction: ‘The box was the most telling object; regularly kicked across the floor by the unsuspecting public, a gallery assistant wearing white gloves would replace it to its original position in a vain attempt to protect the object from human contact.’

Indeed, given that the preservation of the shoe box is clearly not Orozco’s priority, we might look to the age of contemporary art as one consciously embracing the idea of a work’s ‘natural life’: the marks and deformations gained in ‘mistreatment’ might be considered positively, as part of the continued making of a piece through time. Viewer intervention might currently resemble a transgression, with Meret Oppenheim’s Cannibal Feast (1959) nonetheless among its precedents, but the art world has long been a place where ‘crimes’ have been more readily legitimized.

Fryer points out that the legal issue of copyright is extremely different in a fine art context than in others: copying and appropriation are readily embraced here where plagiarism would be subject to sanction in literature. The Dadaists, according to Walter Benjamin exemplify this distinction: ‘Their poems are ‘word salad’ (...). The same is true of their paintings, on which they mounted buttons and tickets. What they intended and achieved was a relentless destruction of the aura of their creations, which they branded as reproductions with the very means of production.’ When image reproduction is taken out of the hands of artists and into those of the press however, the rather non-Dadaist phenomenon of fetishization may occur. And with fetishization the desirability of objects as items to steal might be increased. David tells me that Polly Morgan’s is the nearest example he knows of at the moment of work ‘reaching fetish status through the media’.

In the light of Dadaism, artist intention and control over the immediate effect and longer term fate of works looks to be a key factor in either the staunching or the proliferation of crime. As we have seen in the case of Dada, many conventions established in art history may just as soon be overturned to the profit of process and artistic statement rather than sales. In these terms we might cite Felix Gonzalez Tores and Ai Weiwei as highly progressive; the changes their exhibitions have announced to the permanence and distribution of art has rendered buying and possessing their work nigh on impossible outside of the public sphere. For Gonzalez Tores, who let viewers take the sweets from his installations, theft was never a problem. Eventually, we might predict that the continually evolving nature of the artist's imagination will only be outwitted in the future by the most ingenious of criminal minds.

For more information on ARCA and their Master’s course, in Umbria, Italy: http://www.artcrime.info/

News / Council rejects Wolfson’s planned expansion28 August 2025

News / Council rejects Wolfson’s planned expansion28 August 2025 News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025

News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025 News / ‘Out of the Ordinary’ festival takes over Cambridge 26 August 2025

News / ‘Out of the Ordinary’ festival takes over Cambridge 26 August 2025 Comment / My problem with the year abroad29 August 2025

Comment / My problem with the year abroad29 August 2025 Sport / Return to your childhood sport! 29 August 2025

Sport / Return to your childhood sport! 29 August 2025