And so to bed…

We spend a third of our lives in them, and during Valentine’s week the more traditionalist among us may spend more time in them than usual. But the bed situation in our country is in dire straits. Time to look at its history to glean some examples, writes Yates Norton

The bed has never been just for sleeping in. This is something of which bed manufacturers even today have taken careful note by introducing a range of gadgets which make the mattress perform callisthenics, TVs to appear from the footboard, and enough pillows to make the hardest of peas pass unnoticed by the most sensitive backs and heads. All these additions are not just to aid sleeping, but to invite us to spend our lives in bed and increase that sadly low statistic of a third to the hopeful figure of a whole. For the sleep-deprived amongst us, we have to remember that the bed is not just a vessel of sleep (or lack thereof). This is the naïve mistake of boring people. Franz Joseph I, despite the magnificence of some 1,441 rooms in the Schönbrunn palace, slept in a very plebeian affair lodged between a hard prie-dieu and brown wallpaper.

Now the great and not-so-good, of history know that the bed is more than a mattress and four legs, and have never even given the single bed the thought of day with its depressingly small surface are and its strict Procrustean demands on our bodily arrangements. The Turkish Sultan Ibrahim, son of Murad IV, dispensed with such arbitrary dimensions of a mattress and extended the area on which he was to ‘do justice’ to his concubines, by entirely lining the room with lynx and sable in the Topkapi palace in Constantinople.

Beds of such expansive proportions are clearly not just for sleep and those who associate only sleep with the bed are the blander among us. We need only look at history to see that the bed’s associations are far more exciting than sleep. Murder, lust, wrath, pride, and not to mention sloth, are the prerogatives of the bed; when Pepys wrote, "and so to bed," he was not just going to sleep, but as his diary records, to argue with his wife, to embrace his maid, and, of course, to write his diary. If he were only going to sleep our view of 17th-century England would be the poorer.

The ceremonial bed was the sleepless bed par excellence. Often the apotheosis of a long and uninterrupted vista, the lit de parade, as it was known in France, was the grandest bed of all. For this the king or queen would retire to a small room in which le petit lever would precede le grand lever in the state bedroom which involved getting out of bed only to get back into a bigger and better one; a lie-in of which only the French could have conceived.

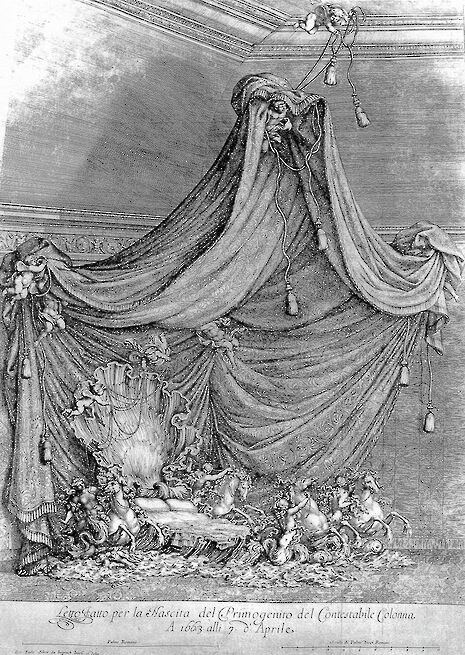

What made the bed so grand were its bed sheets. It is the gloomier amongst us, of which the purveyors of college linen are the supreme example, who purchase bed sheets which have to be by some dreadful necessity ugly or a shade of hospital blue. The owners of the great beds in the annals of history would be horrified at the bed-linen of today. The lit de parade often fulfilled its job description, enshrining the notary within a nest of costly fabrics. Maria Mancini Colonna’s bed is the most exuberant example and was created no doubt to resist any tiresome attempts to ‘make the bed’. A messy bed was legitimised because its counterpanes and sheets were made into artful drapery rather than mere bed linen (compare Tracy Emin’s My Bed and Colonna’s, and you will see the difference).

Rarely would one have been lost alone in such a wilderness of drapery because bed-sharing was very common during this period. College statutes often demand that the student and the master share a bed in line with the most noble of bed-sharing pedigree where even kings would invite a defeated noble foe or admired comrade to lie beneath his covers. How saddened would Francis I be who bedded down with Admiral Bonnivet to find that bed sharing is a prurient and not a noble invitation. Indeed, as soon as erotic pictures (or mirrors for the more narcissistic or lonely lover) were placed beneath the canopy in the 18th century, bed-sharing was no longer a diplomatic venture. If mirrors and erotic pictures were not a stimulant enough, then the (wealthy) impotent could in the late 18th century have a lie on Dr. James Graham’s ‘The Celestial Bed’ in the Temple of Hymen in Pall Mall, where by means of "Oriental perfumes" and the "powerful tied of the magnetic effluvium" the frigid could be warmed up by some "marrow-melting motion".

Unfortunately Viagra came to the rescue in the 20th century and little has been done to expand on Dr James Graham’s excellent idea. What is more, in our post-Romantic society, it has been positively encouraged to ‘do justice’ to one’s lover, as a Turkish Sultan would say, without the bed at all, for example in the corner of King’s library, or for the exhibitionist, the history faculty library. This might have dealt a fateful blow to the bed as a coital receptacle. In our own times silent mattresses for energetic ‘justice’ without the accompanying rubber-duck-like sound-track, a spate of pillows for ease of comfort and the bed’s very own positions have helped continue Dr Graham’s bed reform. But if we want the bed to be better and less sleep-related, it is up to us to continue the example of our illustrious forbears, and like the University’s famous alumnus to always claim, "and so to bed".

News / Students form new left-wing society in criticism of CULC3 September 2025

News / Students form new left-wing society in criticism of CULC3 September 2025 News / Cambridge’s tallest building restored to former glory1 September 2025

News / Cambridge’s tallest building restored to former glory1 September 2025 News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025

News / Tompkins Table 2025: Trinity widens gap on Christ’s19 August 2025 News / Student house could become homeless shelter2 September 2025

News / Student house could become homeless shelter2 September 2025 Interviews / GK Barry’s journey from Revs to Reality TV31 August 2025

Interviews / GK Barry’s journey from Revs to Reality TV31 August 2025