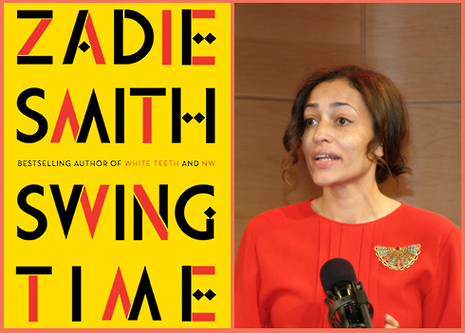

Review: Zadie Smith’s Swing Time

Lydia Sabatini reviews the latest novel by King’s College alumna Zadie Smith

Zadie Smith’s fifth novel returns to familiar territory, dancing through the streets of Kilburn in North West London where Smith grew up – a setting which featured in her debut White Teeth as well as the more recent NW. Autobiographical elements clearly influence the exploration of the early life of a young mixed-race woman struggling with issues of class, race and identity. The plot centres on our unnamed narrator and her formative relationship with her childhood friend Tracey; they bond over being the only two brown girls in their dance class, while being separated by talent and economics. Tracey is talented, but hides her vulnerability under a steeliness that can descend to cruelty, while our protagonist is flat-footed and awkward but an acute observer of others. Tracey’s mother is unemployed, while the narrator’s mother is an autodidact future MP. The two friends grow up together and then are thrust apart. Tracey’s initially sparkling prospects seem to flicker and fade while the narrator ends up working as a personal assistant to pop sensation Aimee, taking her penchant for self-evasion to a professional level. Aimee speaks in bubbly clichés and is callously ignorant of her privilege, so as we follow Aimee’s plans to develop a school for girls in an unnamed West African country, unsurprisingly, tensions begin to rise to the surface.

Smith tackles the issues of identity with characteristic nuance and insight, finding fascinating parallels and contrasts throughout. For example, the narrator looks at an old painting of subservient black boy gazing up at an aristocratic white woman, providing an uncomfortable parallel dynamics inherent in her job in which she caters to the every whim of the rich and powerful white pop star Aimee. Our protagonist is a first person narrator with, ironically, no sense of her own ‘I’. This is a daring stylistic achievement by Smith, for whom this is the first novel written in the first person. For Smith, as she asserted in a Cambridge Literary Festival talk, “style is content” – she said, with the slightest touch of amusement, that this is something she was taught in her time reading English at Cambridge. So, what point does Smith make by presenting the reader with a central character whose core seems more enigmatic than characters in former novels, who can apparently be summed up with a zippy quip by an omniscient narrator? It seems to me to be a more mature writer’s attempt to highlight the slipperiness and relativity of identity, and especially of the self. The idea that all the facets of identity which are thrust upon us by our surroundings may ultimately have a self-alienating and disengaging effect is a potent one in an age where slogans like ‘identity politics’ are thrown around so simplistically and sloppily.

“The idea that all the facets of identity which are thrust upon us by our surroundings may ultimately have a self-alienating and disengaging effect is a potent one in an age where slogans like ‘identity politics’ are thrown around so simplistically and sloppily.”

Pointed explorations of race and identity certainly reinforce Smith’s assertion that she wrote this novel with black girls in mind, and indeed it is the passages about set in the narrator’s childhood which are the most moving and ring the most true; the sections set in West Africa being interesting but less humanly gripping. Many reviews, including that by Sarah Jilani in the Independent have suggested that this specific focus, and the ambivalence of the narrator, does not ‘let everyone in’. I must agree that the narrator’s passivity makes her harder to engage with than, for instance, the two women at the heart of Smith’s previous novel NW, who were each experiencing a profound moment of crisis in their lives. In comparison, Swing Time’s narrator lives in such a continuous state of detachment that there cannot be any such sense of climax or character development.

On the other hand, I think that Cambridge students from less-privileged backgrounds will be able to relate some of the episodes in this novel. For example, the narrator and Tracey are delighted to find and subsequently idolise the mixed-race dancer Jeni Le Gon, whom they spot in various old Hollywood musicals, distinct amongst the sea of white faces. I remember similarly scanning photos at top universities that I saw at open days searching for anyone who looked like me, feeling that if I could find this superficial precedent I somehow would have a better chance of admission. Also relatable is the rendering of the powerful continuous influence of childhood friendships. Smith, speaking at the Cambridge Literary Festival, noted that women in particular have a powerful ability to project things onto somebody else’s life, allowing friendships to become fraught and intense, so that even extinguished friendships still haunt and trouble you further on in life. The fact that old friends have those shared memories makes it all the more distancing when they meet again and are almost strangers.

All in all, the read is enjoyable as Smith’s prose is as effervescent as ever, as one might expect in a book in which the author and protagonist are so clearly in love with dance. But the lack of passion in the lead character means that, while certain episodes and characters remain memorable, the novel as a whole after a time seems to fade away like when the curtain comes down on a stage show that had been watched from far away: distinctive but always a little elusive

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025

Film & TV / Timothée Chalamet and the era-fication of film marketing21 December 2025 News / News in Brief: humanoid chatbots, holiday specials, and harmonious scholarships21 December 2025

News / News in Brief: humanoid chatbots, holiday specials, and harmonious scholarships21 December 2025