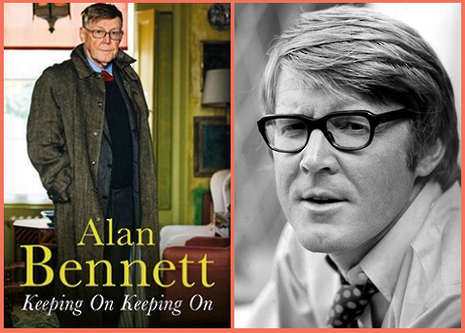

Review: Alan Bennett’s ‘Keeping On Keeping On’

Toby Salisbury is impressed by Alan Bennett’s third collection of prose.

It is natural that writers should keep diaries. What’s less clear is what purpose they serve for the reading public. A premature answer would be that people want to know what a writer is really thinking and that, in some way, we are observing a purer form of thought when we read a personal journal over, say, a novel. But published diaries, particularly those which, like Alan Bennett’s Keeping On Keeping On, are commissioned and destined to be published within an author’s lifetime, are no less engineered for public consumption than any other form of prose. We should therefore resist the temptation to view diaries as a way of peeking behind closed study doors. Instead, we should simply cherish the published diary as a continuation of the unique voices of writers whom we admire.

“we should cherish the published diary as a continuation of the unique voices of writers whom we admire.”

Bennett’s diaries have been published in extract form in the London Review of Books since 1984. These have since been merged into collections representing a decade apiece, with this latest offering covering his diaries from 2005 to 2014, during which the author was in his seventies. It is unsurprising, then, that these diaries often show a man doing the things you might expect of a retiree. He is a dedicated visitor of medieval churches and country houses, not to mention doctors’ surgeries, and he records attending the funerals of too many friends.

But don’t be fooled into thinking that all is twee and cosy; the playwright and author has not let old age and a hip replacement slow his roll. One cannot help but feel impressed by the amount of travel the septuagenarian Bennett undertook in these years, or by the many prestigious engagements he attended. And it’s not just play that’s kept him busy, he’s been hard at work too. The half of the volume that is not filled with diary entries is taken up with introductions to new plays, forewords to exhibitions and edited books, and scripts of speeches – including a sermon against the inequality of education provision, read in King’s chapel.

Over the past two or three decades, what has attracted many to Bennett’s writing is his firebrand criticism of British culture and society. Much of this work has been a lament for an England that has been lost, eroded by a process he calls ‘nastification’. Throughout these latest diaries, he lays bare his thoughts on the state of the country as it stands: ‘what we are best at in England… I do not say Britain… What I think we are best at, better than all the rest, is hypocrisy. Take London. We extol its beauty and its dignity while at the same time we are happy to sell it off to the highest bidder… or the highest builder.’ Sentiment like this will be well-received by those who feel that the UK is becoming a less desirable society to live in. Whilst Bennett offers few solutions to the nation’s ailments, many will continue to find comfort in the no-nonsense analysis to which we have become accustomed in his writing.

“Whilst Bennett offers few solutions to the nation’s ailments, many will continue to find comfort in the no-nonsense analysis to which we have become accustomed in his writing.”

For Bennett, politicians are the most complicit in the degradation of society, and as such they receive the shortest shrift. He holds no party card and, although he says he would vote for Corbyn if he were a Labour member (more out of hope than a belief in Corbyn’s competence) his scepticism is reasonably bipartisan. But it is understandably those in power who receive the most acerbic treatment. Among the many hatchet jobs is this gem of a description of Jeremy Hunt, who is said to look akin to: ‘an estate agent waiting to show someone a property.’ Many a medical student will find the imagery to be apt.

Some writers have a way of producing sentences that you feel only they could have crafted. Alan Bennett is one such writer. His cheekiness and even his Leeds accent can be heard throughout Keeping On Keeping On, and he manages to combine this with captivating and beautiful observations. Take this for an example, the sole entry for an October day that was apparently unremarkable except for: ‘A forties sky, broad and blue and streaked with thin cloud and waiting for a dog-fight.’ As a playwright, Bennett has been a master of dialogue and this mastery carries across even into his diaries, where sentences feel spoken by a friendly voice. This is surely the secret to his popularity as a commentator and why a reading from this volume was broadcast live in cinemas across the country last month.

This book provides a bit of everything you might hope for in a diary: reflections on a long and successful career, scathing criticism, as well as witty observations on the everyday and the not-so-everyday. All of this is expertly written, by an author whose warm and familiar voice has penned a decades-long chronicle of British life. At over 700 pages, this is not the kind of book you would read in one sitting. This, like most diaries written by those with a welcome view, is a book to keep at your elbow. It is a book to dip into, reading perhaps a month’s worth of entries at a time, savouring the vicarious musings.

Fans of Bennett will not be disappointed. Those who are not fans will admire at least the wit

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024

News / Fitz students face ‘massive invasion of privacy’ over messy rooms23 April 2024 News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024

News / Cambridge University disables comments following Passover post backlash 24 April 2024 Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024

Comment / Gown vs town? Local investment plans must remember Cambridge is not just a university24 April 2024 Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024

Interviews / Gender Agenda on building feminist solidarity in Cambridge24 April 2024 Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024

Comment / Does Lucy Cavendish need a billionaire bailout?22 April 2024