Review – Elisabeth Vellacott: Figures in the Landscape

Ruby Reding explores the work of the Cambridge-bred artist as part of Kettle’s Yard in New Places and Spaces

Murray Edwards College is an interesting exhibition space. The hallways are long and quiet. They benefit from modern architecture, meaning that light pours in from everywhere and the sound of the fountain delicately echoes through the glass walls.

When I first learned that the entire New Hall Art Collection is not located in a specific and allocated space, I thought that this was slightly underwhelming. Viewing glorified and amazing works of art in a corridor or dining hall rather than a room labelled ‘gallery’ could seem to invalidate the importance of the work: it becomes both ‘art’ and ‘decoration’. But as one porter told me, the entire college is an exhibition – and I think the artwork is also illuminated by these spaces; it exists inside and is a part of college life.

Space is essential to the works by Elisabeth Vellacott on display in the New Hall Collection, as part of Kettle’s Yard in New Places and Spaces. A brief glimpse at her paintings might make it easy to describe her work as whimsical and ethereal, but the newly commissioned text in the exhibition by William J. Simmons rightly reiterates that this kind of ‘gender-based provincialism’ has been adopted by male critics and termed ‘feminine sensibility’.

This way of thinking would be both sexist and narrowing to brilliant work that radically flattens the depth perspective of figures and landscape, bringing together historical, religious and modern subjects in a dimension of spaces that are domestic, natural and architectural.

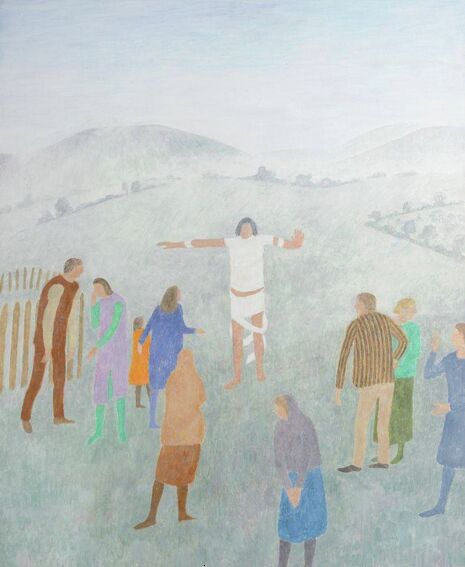

One of the paintings displayed is Lazarus, which pictures a religious, Christ-like figure on a moor with his arms raised so that his body hangs in a cross shape. He is faceless and exists in white, adverse to the various figures gathered around him who stand out in brightly coloured, modern clothes. Their backs are turned, disrupting the relationship to the dominant religious, masculine figure.

Many of Vellacott’s paintings feature settings like this, which resemble a dream landscape or imagined natural space. In the extract provided at the exhibition, Simmons draws on this ambiguity, that “we do not know where these scenes take place; they seem to be everywhere and nowhere”. This, paired with the facelessness and flatness of her figures, is what is so great about Vellacott’s work. It radiates an uncertainty, providing the viewer with both familiar and strange images.

The complementary essay by Simmons is an insightful and useful addition to the exhibition. Also accompanying three paintings are some graphite studies and a small archive of artefacts. One of the studies for ‘Christ Driving Photographers out from the King’s College Chapel’ is witty and in keeping with the Cambridge-focused attention and sensibility of the exhibition. There are some small black and white photographs of Vellacott’s unique triangular house, which provide thought-provoking parallel domestic interior to the private spaces she explores in her work.

This is more apparent as the Kettle’s Yard exhibition is in a ‘new space’. In the same way that Vellacott warps and re-shapes a masculine-dominated art tradition, the exhibition takes place in a space that gives an important voice to female artists. The college collection is one of the largest women’s art collections in Europe, and therefore takes on the important role of providing female artists with a platform – a ‘room of one’s own’.

Although the featured work by Vellacott is limited and only gives us a small insight into the depth and body of her art, it is important as part of a wider discourse. Part of this contemporary dialogue of which New Hall Art Collection is a partner is the project ‘A Woman’s Place’ by Day+Gluckman, which “aims to question and address the contemporary position of women in our creative, historical and cultural landscape” – specifically in the South East of England. It positions the issue of female representation in art in terms of “woman’s interaction with space”.

In the same way, the disruption and combination of figures in nameless or unknown space in Vellacott’s art is reconfiguring the pre-existing representations of historical and religious figures with modern ones, compressing both depth perception and time. Now that this exhibition has placed her artwork within this ‘new space’ it serves to be an even more ingrained reclamation.

Vellacott’s work can be seen through the glass walls opposite that of Eileen Cooper, Julie Held and Maggi Hamburg. The Guerrilla Girls piece greets visitors in the Porters’ Lodge and is also part of the collection. Though the statics have improved since the 1980s when their posters were made, still less than 25 per cent of solo exhibitions at the Tate Modern, Hayward and Serpentine galleries were by women from 2007 to 2014.

There are many more statistics like this. An article by Maura Reilly in Art News has an excellent analysis of how representation remains an economic and social issue in the contemporary art world. This is just some of the evidence of why this exhibition is important, but more specifically this exhibition allows Cambridge to become part of the conversation.

Kettle’s Yard in New Places and Spaces is not just intellectually and visually stimulating, but it is also a kind of action. It’s interesting for those interested in the issue of women’s representation in art and the role that Cambridge has played within it. No other exhibition I have visited in the UK has allowed such a strong, distinctive voice of women’s art. It is an ingrained sense of political relevance and female solidarity that makes this exhibition unique.

Elisabeth Vellacott’s work is on display from 2nd November 2016 – 15th January 2017, 10am-5pm at Murray Edwards College

Comment / Why shouldn’t we share our libraries with A-level students?25 June 2025

Comment / Why shouldn’t we share our libraries with A-level students?25 June 2025 News / Lord Mandelson visits University30 June 2025

News / Lord Mandelson visits University30 June 2025 Features / 3am in Cambridge25 June 2025

Features / 3am in Cambridge25 June 2025 Theatre / Twelfth Night almost achieves greatness26 June 2025

Theatre / Twelfth Night almost achieves greatness26 June 2025 Features / What it’s like to be an underage student at Cambridge29 June 2025

Features / What it’s like to be an underage student at Cambridge29 June 2025