In conversation with Akala

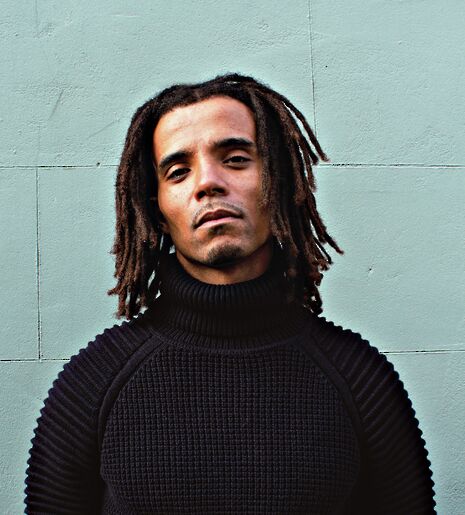

Leila Mani Lundie speaks about art, politics and cultural appropriation with Akala ahead of his performance at the Cambridge Junction on 31st October

In the decade since his debut album It’s Not a Rumour was released, Akala – rapper, writer, educator and poet – has released five more albums, carved a name for himself as one of Britain’s most politically vocal artists and is now embarking on something of a victory lap. His upcoming album and tour, both titled Ten Years Of Akala, are retrospective looks back at the past decade. The album is a compilation of 20 songs chosen by his fans that gives “the power to the people”, and the tour promises to be a massive celebration, stopping off at the Cambridge Junction on 31st October.

I caught up with Akala to discuss his upcoming tour and find out the thinking behind his work. The first thing I ask him is what we can expect from the tour, and he launches into the first of many fluent, minute-long speeches. “What we’ve always prided ourselves on is having a level of production that is two or three steps beyond the size of the venue we’re playing [in]. We’ve mastered all of the music and the individual elements separately so it gives a really phat sound. We’ve got a drummer, a DJ. We’ve got full visuals for the whole set, costume changes. That kind of real theatrical, showmanship energy. But also, it’s been 10 years and there’s a lot of material so I’ve had to essentially carve up songs to fit in a narrative that covers the last 10 years.”

For Akala, art and politics go hand-in. To get a sense of this, you need only listen to angry, politically-charged 'Fire In The Booth' to be convinced that his politics is intrinsically tied up with his art: “Cheap slave labour, big corporations / They come out of jail, can’t get a job / So when we celebrate going to jail / We are literally celebrating enslavement”. I ask him about the relationship between art and politics: should art be political? “Art is political. If we talk about politics as the science of managing human affairs, there’s nothing that isn’t political. The price of rice is political. How much it costs for a pint of milk at the corner shop is political. Everything is political. It’s not just what happens down in Westminster.”

With an almost superhuman eloquence, and without needing to pause to think about what he wants to say, he fluently continues: “One of things I really wanted to communicate to my generation really, particularly to young people who feel politically disenfranchised, is the sense of their own political power. Because they might not choose their leader directly, or feel that they have a stake in what goes on in Westminster, it does not mean they’re not engaged in politics. Opening a soup kitchen in your local neighbourhood is a political act. Helping out the homeless is a political act. Being a teacher that goes the extra mile for your students is a political act. All of those things are forms of political engagement. Choosing to make music that questions the dominant culture is political. Choosing to make music that reinforces it is also political. The difference is, when rappers particularly but musicians in general, choose to make music that reinforces the dominant culture, no one ever says ‘Oh – that’s political’. Artists can choose to engage in progressive politics, or to pretend that they’re some sort of apolitical norm – which I don’t believe that there is.”

The importance of knowing and understanding roots comes up on numerous occasions during our discussion. Akala’s own mixed ancestral roots – his father is Jamaican, his mother Scottish – are highlighted in his newest single, 'Giants'. Unlike most of his previous music, 'Giants' is more reggae-influenced. As someone who “grew up on the Jamaican sound system”, why did it take him 10 years to release a reggae track? “I just feel in general I avoided reggae because it was the most obvious thing for me to do.” The track is something of a “homecoming” for him, a homecoming inspired in part by his upcoming BBC 4 documentary Roots Reggae and Rebellion, which will air this month, and his recent trips “back to Jamaica”.

He brings up roots again when I ask him what he thinks of the current state of UK grime and hip hop, given that Skepta has just won the Mercury Prize and the scene is in “undoubtedly the strongest position probably it’s ever been in”. “A lot of people who actually practise grime and hip hop don’t know that grime in particular is a very direct adaptation of Jamaican sound-system culture. I feel in some ways I have a place in making my upcoming album and having that whole discussion around the impact that Caribbean music has had on British popular music.” And how can the UK grime and hip hop scene sustain this current flourishing of grime into something solid and permanent? “Understanding the roots is a key part of that. Understanding that Count Suckle owned a massive club in Paddington in the 60s – he was one of the first people who brought sound system to Britain. There’ve been successful black musicians in Britain for a very long time. Whether or not we’ve created our own sort of mini-industry remains to be seen. And I think that the big difference between African American music and black British music is that sense of permanence.”

Somewhat self-indulgently, I finish my interview by asking him about cultural appropriation. I mention that university spaces – Cambridge, in particular – are hotspots for cultural-appropriation-based controversy. Really, as someone who cares about the issue and is interested in everything he has to say, I just want to listen to him powerfully articulate why it’s so important that it’s rebelled against. True to form, Akala fires off another one of his eloquent speeches. “I think it’s about first of all understanding what appropriation is and isn’t. See, a lot of people seem to deliberately want to misunderstand the issue. Cultural exchange – borrowing from different cultures – is beautiful, healthy, perfectly normal, and in fact has been one of the key drivers of human progress forever.”

So what, then, is the big deal about cultural appropriation? “I think appropriation, and specifically around the music industry where there’s been a lot of sensitivity, is because black American music has been the driving force of the 20th-century American music industry. But black people were pioneering this industry in America at a time when they legally didn’t have the right to vote in certain states, where there was racial segregation, where they were literally prevented from going on the radio in some states in favour of white DJs who ‘were told to talk black’. In that history, where people believe that Elvis Presley invented rock 'n' roll – which, of course, he did not – there’s a sensitivity around acknowledgement of origin. This doesn’t only happen among racial lines, it happens along lines of class and gender. Britain is becoming a more democratic society because of the actions of poor people. Then the British elite turn round and say ‘Hey, it’s British values’. No, it’s not fucking British values why poor people can vote, or why women can vote, or why you can’t hang poor people down at Tyburn anymore. It’s people-based activism. So this is not just about class, it’s about people with power and influence stealing the achievements of people that have less power and influence and resource. And that occurs all over the world, in all cultures, along various different ethnic, cultural, class and gender-based lines. But in the context of modern music it’s often been a racialised conversation.”

Throughout our interview, I get the sense that Akala is someone who is unashamedly proud of his art and his work – and rightfully so. Not only does he reach hip hop fans, but he is also able to draw people to his music through articulate and impassioned communication of his politics. How has he managed to attract such a diverse following? “I have a really interesting and eclectic group of people that I would say engage with what I’m doing in a much wider sense with than it just being, say, a three-minute pop song. I deliberately wanted to cultivate that from the beginning. I wanted to affect and provoke thought and make people think and feel and engage with what I’m trying to put out. I put my heart and soul into my art: it's not just something I do because I wanna make money.”

“I’m lucky enough that I’ve got to a position where I can sustain myself as an artist, which in this world is a huge privilege. I didn’t come into art like ‘right, I wanna be a pop star’. I wanna make art that I really fucking love, and hopefully other people do too”

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025

News / Cambridge Vet School gets lifeline year to stay accredited28 November 2025