A.E. Housman: The forgotten Cantabrigian

Mimi Trevelyan-Davis discusses the importance of remembering the Trinity fellow and Professor of Latin

At Cambridge, you can become desensitised to a long list of names of illustrious men (and it is nearly always men) who have walked through the halls of your college or faculty before you. I have my own hazy recollections of reading through the Wikipedia page for my then future college, Trinity, with increasingly wide eyes at the names I recognised: Lord Byron, Francis Bacon, Eddie Redmayne to name a few from a long and prestigious list. The walls are seeped in history that often feels at one with the character of the country itself; grandees of politics, literature, science and mathematics. It is thrilling to imagine that maybe once Mel Giedroyc hung about in my old room or if Vladimir Nabokov dreamt up a good line at this seat in the library.

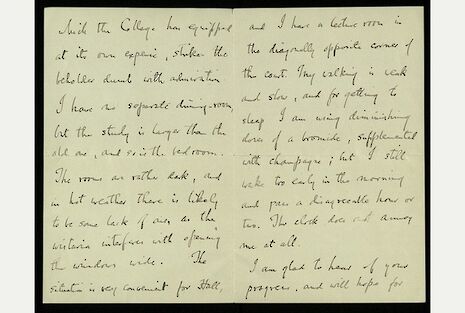

You will note I did not mention A.E. Housman in my previous lists, simply because I thought the reference was quite obscure. Housman was a fellow of Trinity, a Professor of Latin and the author of The Shropshire Lad but his memory is simply not celebrated in the way of his famous counterparts and contemporaries. He was in the local headlines not long ago, however, following the discovery of a cache of his personal letters to his godson, Gerald Jackson, from 1927 to 1936, detailing his life in college. From despairing over boat club losses to discussing his diet, they are an interesting foray into life at Cambridge during the inter-war period. The entertaining and sometimes poignant collection, now housed in Trinity’s Wren Library, details his dinners of fifty-two oysters, enjoying ox-tongue straight from Fortnum and Mason and gifts for the nurses who looked after him in his nursing home.

Housman’s personal life barely gets a mention – which is none too surprising if you’re familiar with it. Matriculating in 1877, his undergraduate degree at St John’s, Oxford, was defined by his close relationships with A.W. Pollard and Moses Jackson, the latter of which Housman was in love with, and was the father of his godson Gerald, the recipient of the letters. His sexuality was not publically known until the posthumous 1967 publication of De Amicita (meaning ‘Of Friendship’, which was dedicated to Jackson) by his brother, Laurence. Laurence Housman wrote that his reason for publishing it was to allow readers to have a “fuller knowledge” of a man who “in his own lifetime, could not let himself be better known”, and the hope that one day society itself would gain the “common sense” to treat gay people “less cruelly” and “less unintelligently”. De Amicita was published 16 days before homosexuality was legalised by the 1967 Sexual Offences Act.

The first time I came across Housman and his tragically familiar backstory was during a performance of The Invention of Love, one of Tom Stoppard’s more obscure titles and a biographical play of the Housman. In true Stoppardian style, it begins with the death of the protagonist and is a long mediation on love and loss through the lens of Housman watching his younger self at Oxford, with a second act defined by the Oscar Wilde ‘gross indecency’ trial. It is very wordy, with long digressions into Latin and Greek scholarship, but the climax of the play, a conversation between Wilde and Housman, is emotive and beautiful. This conversation is defined by regret – Wilde regrets nothing, and suffers for it, writing in his prison masterpiece, De Profundis that “to regret one’s own experiences is to arrest one’s own development”. Housman, meanwhile, desperately wishes he could have died for Moses – “but I never had the luck”, he exclaims throughout the play.

The tragic mirroring of Wilde and Housman, living different lives but still fundamentally imprisoned by the same oppressive society, reflects on how we remember historical LGBT+ figures. They are defined by their sexuality and by their tragedies, whether they were great, such as Wilde’s imprisonment and lonely death, or smaller (although by no means less painful), like Housman’s universal suffering at the hands of unrequited love. My article here has once again fallen into this paradigm: tragic biography, unjust laws and a smattering of untimely deaths. However, we cannot shy away from this pain either: the injustices and oppression of the past in society defines us all, whether it is homophobia or racism, and should not be brushed aside from our collective memory just because it is uncomfortable. Embracing, recognising and learning from these injustices are vital if we are to look forward.

So read Housman’s letters; laugh at his propensity for oysters; go and read The Shropshire Lad or watch The Invention of Love (they’re very good), and dwell on what it means to remember

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025