Sexuality and sensuality: hidden secrets of the Fitzwilliam

In the first part of her series, Isabella Bonner-Evans exposes the erotic in John Everett Millais and Stanley Spencer’s work

Many of us wander past the Fitzwilliam Museum day by day on our way to lectures, coffee shops or libraries without sparing it a second thought. You might assume the collection is neither exciting nor ground breaking, yet there are many magical pieces with incredibly interesting (and covert) symbolism and narratives. It is well worth paying a visit.

The theme of human sexuality permeates the history of art from Ancient Greek sculpture to contemporary works such as that of the Young British Artists. Desire, sex and intimacy appear to be as undeniable in art as they are in human experience. A few particularly special works within the Fitzwilliam explore and expose these hidden and secret feelings.

The eminent John Everett Millais’ The Bridesmaid (1851) hangs discretely in the corner of the Pre-Raphaelite room of the museum. It was painted during a period when Millais himself was negotiating his way to sexual maturity and on the search for love and marriage. When first observing this stunning little painting, one is taken back by the creative use of striking colour and the beauty of the woman within; she has long, flowing golden hair and piercing eyes.

However, one is unlikely to immediately unpick the subtle symbolism which exposes the narrative. The bridesmaid wears an orange blossom over her breasts, a symbol of chastity well known to a Victorian audience and customary attire for a girl in her role. This suggestion of abstinence contrasts with the apparent longing in her eyes. The girl is carrying out a ritual of desire; she runs the wedding cake through the ring in her hands nine times, at which point her lover is supposed to appear in a mirror – in this case the mirror is the picture plane. Thus, as we gaze at this piece, we unknowingly become the ultimate object of her yearning.

To further emphasise the undertones of sexual desire within this seemingly innocent portrait, Millais disrupts the symmetrical composition with a phallic, rigid and upright salt shaker. The salt shaker itself is both literally part of the ritual which the bridesmaid carries out and a symbolic trope in Millais’ work. The painting, Lorenzo and Isabella (1848-9) shows a spilt salt shaker positioned within the composition next to the hint of a groin, which, according to art historian Carol Jacobi, suggests ejaculation. When comparing the presentation of the salt shaker in each work it becomes apparent that The Bridesmaid is about repressed sexual desire – the shaker is upright rather than spilling salt.

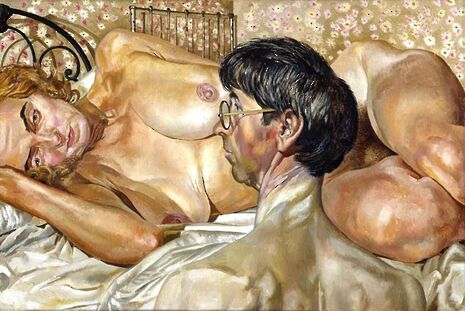

Skipping forward almost a century, another example of interesting hidden sexual symbolism and narrative appears in the form of Stanley Spencer’s Self Portrait with Patricia Preece (1937). Spencer was an English artist from a small town called Cookham. During his time at the Slade School of Art, he consistently returned there as his safe haven. He was most famous for recreating the religious scenes of his daily life, but at pivotal points in his life he would paint intense self-portraits.

His self-portrait in the Fitzwilliam appears, at first, to be a depiction of his loving relationship with the sitter who reclines naked. However, with closer observation, it becomes immediately clear that this is not the case. The sitter appears uninterested, while Spencer is uncomfortable, straining his neck. In the background, a second bed can be seen emerging from the floral wallpaper and challenges the idea of domestic bliss spent in a marital bed. From close study of Spencer’s biography we can gauge that the sitter is his second wife, Patricia Preece. Preece was a local socialite in Cookham. However, she harboured a sexual secret: she was a lesbian. Spencer became infatuated with her almost immediately upon their first meeting in 1929, and describes painting Preece as feeling like an ant crawling over her body.

From extensive research it becomes clear this is the most intimate the two ever were. As we look closer into the panting, we spot Spencer’s flushed cheeks suggesting embarrassment and perhaps sexual arousal. Further, the care and detail with which he paints her fluffy pubic hair when compared with her head hair implies his real focus here: her hidden sex

News / Government announces £400m investment package for Cambridge25 October 2025

News / Government announces £400m investment package for Cambridge25 October 2025 Arts / Why is everybody naked?24 October 2025

Arts / Why is everybody naked?24 October 2025 News / Cambridge don appointed Reform adviser23 October 2025

News / Cambridge don appointed Reform adviser23 October 2025 News / Climate and pro-Palestine activists protest at engineering careers fair25 October 2025

News / Climate and pro-Palestine activists protest at engineering careers fair25 October 2025 Comment / On overcoming the freshers’ curse22 October 2025

Comment / On overcoming the freshers’ curse22 October 2025