Week 4: H e a d s p a c e

In her fourth weekly column, Rhiannon Shaw discusses how to tackle talking to family about mental health

Telling your parents you’re not ship-shape up in the brain area is a great way to add a dash of excitement to any family occasion. Will they get angry? Will they start crying? Will they kick you out for being ungrateful about all the things they’ve given you?

“Back in my day I had to work at a fish and chip shop to pay my way through university and it was the Seventies and I didn’t even have an iPhone – you didn’t see me wallowing in a pit of despair!”

Cross-generational communication can be difficult even at the best of times. Explaining why you’d prefer they shared cute cat gifs rather than endless ranting Daily Mail articles on their Facebook wall will end in fury rather than fluffy kittens. Trying to convince your grandmother that Skype isn’t a way for criminals to see into her kitchen won’t stop her from covering up the camera with her finger every time she wants to chat to your uncle in Australia. Pointing out that neither you nor your partner burst into flames because you slept in the same bed will garner the retort that they never thought that would happen – just maybe that the neighbours would take you off the Christmas card list.

Mental health issues aren’t new and they weren’t ‘invented’ by some internet entrepreneur who has it in for your parents. But the more and more open we become about depression, anxiety, eating disorders and addictions, the more foreign the world becomes to a generation that just didn’t talk about it. It’s unlikely that anyone of any age or walk of life has sailed through without, at some point, at least knowing someone who has a mental illness, but it may have been brought to their attention as a secret – an embarrassment, even.

And maybe we have a right to be angry about that. I certainly get angry thinking about the people, just like me, who were sectioned and isolated from their families, treated like criminals rather than given the necessary help to become healthy and happy again. I get angry that so many were told to just ‘get on with it’, because their problems weren’t worth anyone’s time. I get really angry when I think of those whose way of life - their gender, their sexuality, their way of thinking - was wrongly and horrifically pathologised. I’m not saying that any of this has ended, either. Injustices in mental health are, unfortunately, not a thing left in our grandparents’ or our parents’ youth, but at least we’re making strides to talk about it.

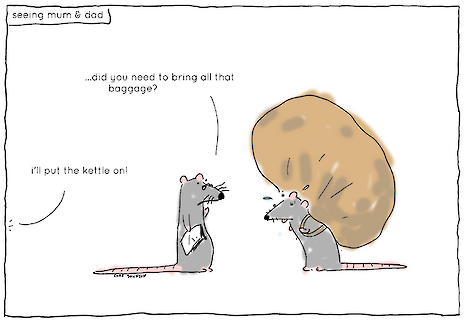

This is one reason why I think you should speak to your parents about mental health, even if you’re healthy. Talking about an article you’ve read or a campaign at uni is a simple way to broach the topic. Point out the lovely cartoons that my pal Luke Johnson does for this column every week. They’re pretty cool.

Another reason is the simple fact that your family is an important support network, and, assuming they listen to your concerns, they can be the first people you call in a crisis. I’ll never forget coming home after a terrible few weeks and getting a hug from my little brother. You’d be surprised how unexpectedly kind and wonderful people can be if you give them a chance.

But for every hero of the hour, there’s someone who’s… maybe… a little bit shit and unhelpful. It’d be stupid for me to demand that you tell your parents because telling your parents is definitely going to solve everything – I’ve heard enough horror stories to know that isn’t true. Bringing up your university counsellor in conversation may not feel like the safest thing to do when your father has made a disparaging comment about someone at work being ‘lazy’ rather than seriously ill. Going to a parent and having your experience utterly invalidated can make you believe, incorrectly, that you’re alone.

There aren’t any hard and fast rules when it comes to mental health, but even if you feel like you can’t tell your parents or family members, I urge you to find yourself a surrogate family who know about your illness and can check up on you whenever, wherever. Opinions aren’t going to change quickly and you shouldn’t put pressure on yourself to try and make your family see sense when your mental health is at stake – it’s exhausting, it’s dangerous and what matters is you getting better. Fighting some outdated social mores is tough enough, even when you’re feeling fabulous.

I’m lucky and I don’t take that lightly. If you’re not as fortunate as me in the random lot of family allocation, don’t ever think that you’re alone. It may sound cheesy (pretty camembert-y, in fact) but you will find people who love you no matter where your head’s at. I promise, they’re about.

News / Cambridge students set up encampment calling for Israel divestment6 May 2024

News / Cambridge students set up encampment calling for Israel divestment6 May 2024 News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024

News / Cambridge postgrad re-elected as City councillor4 May 2024 News / Proposed changes to Cambridge exam resits remain stricter than most7 May 2024

News / Proposed changes to Cambridge exam resits remain stricter than most7 May 2024 News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024

News / Some supervisors’ effective pay rate £3 below living wage, new report finds5 May 2024 Fashion / Class and closeted identities: how do fits fit into our cultures?6 May 2024

Fashion / Class and closeted identities: how do fits fit into our cultures?6 May 2024