We should fight the privilege, not the privileged

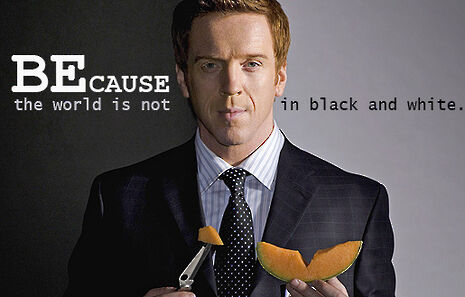

The Damian Lewis row calls into question the best way to deal with privilege, says Alex Mistlin

A recent row at Acland Burghley School, a north London comprehensive and my alma mater, illustrates how divisive the issue of privilege is in British society. The row erupted after former pupils argued that it was inappropriate to invite old Etonian actor, Damian Lewis, to take part in the school’s 50th anniversary celebrations. Given that Lewis is an amiable and popular member of the local community and the school is a performing arts college it seems an eminently sensible decision to invite the Homeland star. However, a small group of campaigners did not agree. They argued that Lewis should be disinvited because of his “elitist education that provides a small minority with vastly more opportunities than the rest.” This is undoubtedly an admirable sentiment but it represents a simplistic analysis that does not adequately address social inequality.

I’ll begin by conceding the fact that the protestors had a legitimate point. Our society cannot be considered truly meritocratic while it is dominated by a privately educated elite. In 2014, a study by the Social Mobility and Child Poverty Commission found that 43 per cent of newspaper columnists, 33 per cent of MPs and 71 per cent of senior judges were educated at independent schools. However, it is unfortunate that too often this legitimate frustration with an unfair system takes the form of reverse snobbery. The danger of this is that it sets a bad precedent by which people can be attacked ad hominem for their background. You might think this a trifling issue and to some degree it is. But ask yourself: would a society where people are pigeon-holed based on schooling benefit those who currently sit at the top or the bottom of the pile?

This is not to say that those who seek a more equal society should not call for radical upheaval. In fact, that this anger is often directed at easy targets like Damian Lewis reflects the small-mindedness of many campaigners. Snubbing or criticising someone who has benefited from their privilege might make you feel better but it does not address the real drivers of inequality.

Papering over the cracks with misplaced anger might mean that there are a few less prominent public schoolboys, but it will not change the status quo. For instance, inequality in early years provision means that privileged children far out-perform their peers well before they take up that place at Eton or Winchester. Recognising the endemic nature of the problem is the first step in finding real and lasting solutions.

Counter-intuitively, to create a more progressive, egalitarian society we must strive to extend privilege by distributing opportunities to as many people as possible. This means encouraging children at comprehensive schools to emulate the example of successful people from all walks of life. In other words, we must adopt a nuanced approach that recognises the role that privilege plays in the success of people like Damian Lewis without dismissing them as individuals.

Social mobility cannot exist unless everyone works to break down the class barriers. This means being sympathetic towards those who would like to use their considerable privilege to prevent others being let down by a system from which they have benefited. Prejudice towards the privileged has the pernicious effect of entrenching class divisions while alienating those who have the power to address the issue.

As an elite institution, the University of Cambridge is in a difficult position. As a product of an unjust society, its admissions statistics make for grim reading. Independent school pupils are five times more likely to go to Oxbridge than those educated in the state sector, and only one in every 1,000 students eligible for free school meals get in.

The difficulty for Cambridge is how to distribute places more equally without compromising the first-rate education that makes this university the envy of the world. While quotas are a blunt instrument, measures must be taken to ensure that places go to those who truly deserve them. Studies have repeatedly shown that students from state schools routinely outperform students from the independent sector with the same grades.

Perhaps admissions criteria could better acknowledge the different contexts in which grades are attained in order to better identify the students with the most potential. This is an incredibly complex problem that cannot be unilaterally solved, but the admissions process must adapt to ensure Cambridge is academically rather than socially elitist.

To the dismay of the protestors, Damian Lewis bravely accepted Acland Burghley’s invitation, insisting that his critics had missed the point. He is right; reverse snobbery does not solve the privilege problem. It merely perpetuates it.

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026

Comment / Plastic pubs: the problem with Cambridge alehouses 5 January 2026 News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026

News / News in Brief: Postgrad accom, prestigious prizes, and public support for policies11 January 2026 Theatre / Camdram publicity needs aquickcamfab11 January 2026

Theatre / Camdram publicity needs aquickcamfab11 January 2026 News / Cambridge academic condemns US operation against Maduro as ‘clearly internationally unlawful’10 January 2026

News / Cambridge academic condemns US operation against Maduro as ‘clearly internationally unlawful’10 January 2026 News / SU stops offering student discounts8 January 2026

News / SU stops offering student discounts8 January 2026