May Week: a relic of an elitist past

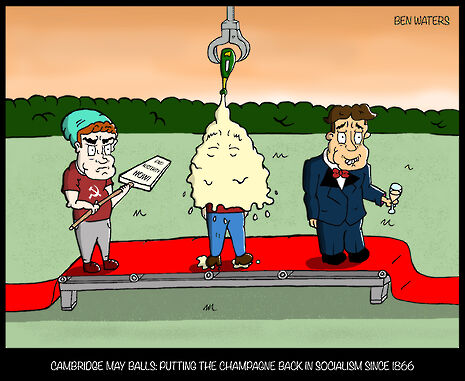

Can we really excuse ourselves for the sheer decadence of May Week, asks Noa Lessof-Gendler?

Glittering gowns, white tie, silent discos, world famous rock bands, smash hit DJs, extravagant gambling tables, rainbows of flowing cocktails and champagne, oysters, burgers, caviar, chocolate fountains, helter skelters, bouncy castles, inflatable observatories, night punting, balloon rides, four course breakfasts, fireworks displays over the rooftops of Cambridge…

It’s a familiar scene, one many of us have experienced first-hand. Even the most modest May Balls and June Events provide unlimited alcohol, delicious food and extravagant performances. And it’s a glorious scene, one which belongs in a world of revising on the backs in golden sunshine and getting firsts in all of your exams – the world in which the glossy mirage of a perfect Cambridge is the reality. In that world, students don’t need bursaries which are scraped together in the annual telephone campaigns, the university counselling service is well-funded with plenty of staff to support the eighteen thousand-strong student body, and every employee is paid the living wage.

For fifty-one weeks of the year, I’m well aware that this version of Cambridge simply doesn’t exist. I read testimonials revealing students’ experiences of having to switch rooms halfway through the year because their finances take a turn for the worse; I watch friends staying in for weeks on end because they can’t afford a night out; I hear rumours that the college subcontracts our bedders so they can cheat the living wage pledge and pay less than £7.65 an hour to clean our mountains of mess. For fifty-one weeks of the year I know this, and I feel deeply grateful for my financial privilege. Many individuals across the university feel the same. We support campaigns against raising tuition fees, we sign petitions to force colleges to acknowledge that not all students are able to support themselves, we try our utmost to contradict the ‘Guardian’ perception of us Cambridge students as privileged brats with more money than we know what to do with.

Unfortunately, for the fifty-second week of the year, that is precisely what we are. There is no plausible excuse for the astonishing displays of wealth that are the Cambridge May Balls. They exist out of their time, contradictorily canonical, remnants of a time when Cambridge really was just for the rich, and when social elitism was the norm. In an age when we presumably know how to check our privilege and class is recognised as a construct to be dismantled, how is it that we are so able to numb the guilt and indulge in days of lavish opulence against which our morals usually protest so ferociously?

First, we like to make the most of the ‘everyone else is doing it so why shouldn’t I?’ excuse. If the rest of our friends are okay with forking out £300 over the course of a week on balls, then there’s no one to berate us for it, and we can all turn a blind eye on our own hypocrisy together. We don’t want to be the only ones missing out on the fun – and anyway, it’s cold up there on that moral high ground. No one likes a killjoy.

Second, there’s an element of constructed resignation. We tell ourselves that missing out on all the fun will only be skin off our own noses and won’t make any difference in the grand scheme of things, just like boycotting Primark won’t mean that Indonesian seamstresses will be given proper pay, or how becoming a vegetarian won’t bring down the corrupt cattle industry. If we don’t buy that ticket, someone else will, so we might as well just partake. Besides, if we don’t spend the money now we’ll only spend it on booze and food over the summer instead. There are plenty of music festivals we could be attending, and the food and drink isn’t even free there. What difference does it make?

Most of all, we let ourselves get away with it because May Week is so fun. For those of us with the cash to spare, there’s simply no better opportunity to let loose and take advantage of the opportunities at our fingertips.

I like moonlight punting in my Ted Baker; I like drinking champagne with friends; I love oysters (which, like most of the rest of the world, I don’t eat very often). Given the chance, who wouldn’t don their finest gladrags and dance until dawn on the lawns of a castle? May Balls are the stuff of the most fantastical of fairy tales. After seven weeks of stress and work, the glamour and glory of May Week is irresistible – and I don’t blame anyone for succumbing to it.

Nonetheless, I think we need to start a conversation about what this annual week of revelry represents. It contradicts our attempts to instigate financial equality across the university by virtue of the fact that some can afford to experience this highlight of Cambridge life while others can’t.

When Guardian writers label Cambridge an elitist and outmoded institution, our protests are undermined by our ready acceptance of May Week. And when we tell prospective students from less privileged backgrounds that Cambridge is a place where everyone feels equal and where we’re judged by the size of our brains rather than the size of our bank accounts, we’re lying. There are times when the gulf of wealth becomes apparent in ways that are seen in few other places. While May Balls are the norm here, equality simply is not.

I’ve still got tickets for Corpus and King’s Affair, though. And I hate myself for it.

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025

News / CUP announces funding scheme for under-represented academics19 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025

News / Cambridge welcomes UK rejoining the Erasmus scheme20 December 2025 Science / ‘Women just get it more’: autoimmunity and the gender bias in research19 December 2025

Science / ‘Women just get it more’: autoimmunity and the gender bias in research19 December 2025