It’s time to talk about anorexia

Isla Cowan talks candidly about coming to terms with anorexia

I’ve struggled with anorexia for five years now and enough is finally enough. Being at university has given me the strength to be more vocal about my illness. At school, I felt so ashamed after I was diagnosed due to stigmatisation and I think that this fuelled the sense of delight I found in the secrecy of my illness. It was mine. My private rebellion.

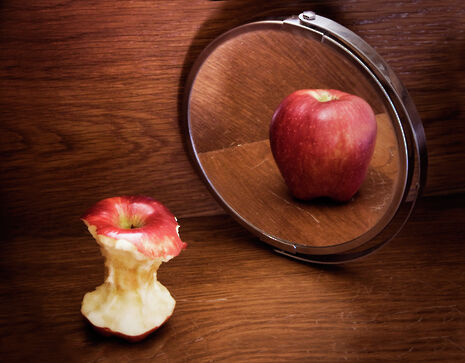

But at Cambridge mental health problems seem to be normalised. I don’t mean in a way which sanctions or encourages them, but in a positive way. I no longer consider myself insane for feeling how I do or feel alone in my struggle. I don’t feel I have to live up to my label and keep on starving myself to meet others’ expectations of how an anorexic should behave. Just because I manage to eat a Snickers in the college bar does not mean I’ve been “cured”. Just because I’ve put on some weight does not mean I am freed. Anorexia is in the brain, not the body.

Fighting anorexia properly, after years of a feigned battle which I've only ever half embraced, is incredibly difficult. It feels as if I’ve been left with all the bad bits – the anxiety, guilt and self-loathing – without the euphoric feeling of control and thinness. And, the bad bits can be really bad: I was very lucky that I could only find a butter knife when, in the grips of guilt, I was determined to cut the fat out of my stomach.

Everyone blames the media: “no wonder you want to be thin when you look in all these magazines!”. To begin with, I don’t read magazines. Next, anorexia is a force which comes from within. Yes, being bombarded with photos, air-brushed within an inch of their life, doesn’t help. But it is not the cause; it is merely a catalyst. Centuries ago, anorexia could manifest itself in the desire to be closer to God, with religion taking the place of the media as the motivating factor for starvation.

I won't preach like other reformed anorexics who condemn skinniness (not least because I am nowhere near reformed). Some people are naturally slender and that's fine, just as much as some people are naturally curvy. I refuse to be a skinny-hater and, after witnessing many arguments on Instagram, I refuse to attack the people using “pro-ana” social media, as some so-called “pro-recovery” ambassadors have done. The “pro-ana” profiles belong to those who are still very much caught up in the world that I once was in. I feel sympathy for them, not animosity that they're bringing down the “pro-recovery” cause.

I also miss being “good” at being anorexic. I wasn’t just “good”. I felt like I was the best, and I liked being the best. I miss weighing less than 45kg. I miss the feeling of pride in an empty stomach and visible bones. I miss its constancy and reliability. Even as I write this, I’m considering the prospect of trying to skip lunch.

When I crave the comfort and confidence which nothing but anorexic restriction can give me, I try to remember anorexia’s faults. Not just the shattering guilt and anxiety but the tangible repercussions: the dizzy spells and fits, my body’s attempt to grow a fur to keep me warm, my slowed heart rate, failures of concentration, ruining family celebrations and holidays, insomnia, and digestive problems. It may feel amazing to be stick-thin and strong-willed but I’ll tell you what doesn't feel amazing: shitting yourself when you're sixteen years old due to three days of nothing but coffee and diet pills.

The worst part? Being a liar. Anorexia forced me to lie to people I loved and I can never undo that. It breaks my heart. After a few bad weeks in Lent term, I took it upon myself to call my Mum. And I was honest with her about my illness for probably the first time ever.

It had been a hard few weeks. “I've not been managing my eating very well”, was a bit of an understatement, but it was better than nothing. In an instant, I was no longer that little girl shoving handfuls of pasta into my pockets whenever my Mum left the dinner table. I was finally admitting that my addiction to anorexia was wrong and that all my anorexic achievements were empty victories, false friends, because I would never be satisfied. I would never be thin enough until I was a skeleton, quite literally: one in five anorexics die from causes related to the disorder.

While the fallout of trying to eat normally is a continuous battle against the voice of failure, the peaks and troughs of a body accustomed to starving and binging, and the disgusting image I see in the mirror, I know that one day it will be worth it. I think that, in my case, the anorexic thoughts will never fully go away but I can learn to manage them in day to day life and find a way of being okay.

Had someone told me five years ago, even two years ago, that I’d be writing an article which the public could access about my eating disorder, I wouldn’t have replied with shock or refusal. I would have simply said, “but I don't have an eating disorder”. After anorexia, denial was my next best friend. Although I still hate talking about my illness and worry that people will think differently of me once they know about it (or after reading this), being able to vocalise my struggle has really helped. When things are said aloud, the problems become real and, when you can acknowledge that the problem is a real problem, then you can fight it.

Ludicrous anorexic thoughts left unsaid can become rationalised in your private world and that can be very dangerous. Looking back, my pasta pockets and my conviction that I would be able to single-handedly, surgically remove the fat in my body makes me realise exactly how ill I was in the past. It wasn’t really me, it was my illness making me behave in that way, and it has been through the power of honest conversation that I have become able to appreciate that.

When I’ve let myself be vulnerable and taken confidence in people, I find that they often had suspicions anyway; they were just waiting for me to say it for myself. Talking about it clears the air and my own mind, and it allows me to be closer to the people around me. Everyone, so far, has shown understanding and support. After five years of silence, I have finally discovered the power of speech and I’m beginning to see that the social and psychological gains of recovery are more important than the weight gain.

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025

Comment / The magic of an eight-week term15 December 2025 News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025

News / News In Brief: Michaelmas marriages, monogamous mammals, and messaging manipulation15 December 2025 News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025

News / Uni Scout and Guide Club affirms trans inclusion 12 December 2025