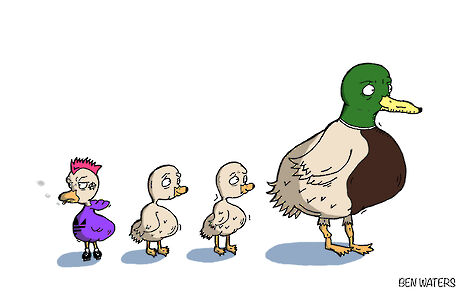

Follow your own path, not others’

We don’t always have to fulfil the demands and expectations of others, argues Anna Rowan

I recently had a supervision which started at noon. Might not sound like a big deal, but I always avoid scheduling supervisions for 12, because I get light-headed if I don’t have breakfast and lunch early. I figured it would be okay, though, because it would only be an hour long, and having lunch at 1.15 wouldn’t be so bad.

The supervision turned out to go on for a lot longer. It was an intense – useful but demanding – not the kind where you can just sit back and listen, the kind where every little thing you say is questioned and re-questioned. At 1.30, my concentration started to go. I felt myself getting shaky and dizzy, and realised I needed a break.

Luckily, my supervisor was fine with it. But as I got lunch, slowly reviving myself with a sandwich and a hot chocolate, I noticed that my automatic reaction was to criticise myself for ‘not being able to keep up’. And I decided that I didn’t want to do that anymore.

I used to see this kind of thing as weak: having to take a break or admitting things were too much. It didn’t matter whether it was about food, or tiredness, or stress. But as I sat in the cafeteria, I thought – why on earth should we let other people decide what is and what isn’t too much for our own bodies? Why do we have to cater to other people’s standards of endurance and why do we feel so bad when we don’t match them?

My supervisor didn’t realise that the supervision had gone over, she wasn’t trying to push my boundaries or imply I was inferior for needing a pause. Unlike her, however, there are lots of people in positions of higher authority, in work and at university, our supervisors, bosses and superiors, who do set explicit expectations of what we should be able to handle emotionally and physically. We should be able to handle the overtime. We should be able to handle the stress. We so badly do not want to break those expectations of us.

And yet, sometimes we find the stress really is getting too much. It seeps into our weekends, into our breaks. We just can’t stop thinking about work, about all there is to do. Time off just becomes either time wasted or time treading water, waiting to have to plunge in again, the inevitable dive. Sometimes we get ill, we get a cold or the flu or bad back ache, and we are expected to keep going as normal when we feel far from it.

We do not always have to fulfil the demands and expectations of others. Sometimes the people who set those demands are not in tune with their own health needs, and enforce their own unhealthy way of working on other people. Sometimes the people who set the standard are so distracted that they are blind to the adverse effects that their expectations are having on others.

We all have the possibility of being in tune with our own physical and mental needs. It can be hard because we rely so much on the feedback of others to know how we ourselves are feeling, and when that feedback is ‘you should be fine’ it can be hard to admit that the reality is far from it. It can be hard because we live in a world that loves proof, proof that we are not okay, and how not okay we are, and we cannot always get proof.

There is no measure for how tired and stressed you are. No one can give you it on a scale of 1 to 10, 8 being the health limit. In hospitals, you decide where you are on the pain scale, because there is no apparatus that can show it, it can only be guessed at approximately by external sources.

Last year, I had a six month internship. I was working for a disorganised start-up company and was given a high work load and a lot of responsibility from the very start. I constantly felt on the verge of a breakdown and I never said anything, until I developed health problems that made it impossible for me to continue working at the same pace, health problems which I am still recovering from. I ignored how I felt for so long because I was always waiting for someone to acknowledge or verify how bad I felt. But no one did, because no one can truly tell you how you’re feeling and often other people aren’t paying that much attention.

This is equally applicable to Cambridge, where only you know how much work you have and only you know how that makes you feel. Don’t wait for someone to pick up on what you’re really going through, because it might not happen. If you’re in crisis, you can feel it. And it is not something to be ashamed of.

Sometimes the standards we feel we have to live up to are broken. The demands imposed on us can be arbitrary and unrealistic, and we are so much more than them. If it is too much, speak up. If you need help, speak up.

Whether it is to friends, to supervisors, to work colleagues, to family or to a counsellor. These expectations only have power if no one speaks up against their validity.

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026

Comment / College rivalry should not become college snobbery30 January 2026 Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026

Features / Are you more yourself at Cambridge or away from it? 27 January 2026 Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026

Science / Meet the Cambridge physicist who advocates for the humanities30 January 2026 News / Vigil held for tenth anniversary of PhD student’s death28 January 2026

News / Vigil held for tenth anniversary of PhD student’s death28 January 2026 News / Cambridge study to identify premature babies needing extra educational support before school29 January 2026

News / Cambridge study to identify premature babies needing extra educational support before school29 January 2026