Dangers of the Cambridge dream

Cambridge isn’t utopia, but we love it all the same

From my window, I look out over church spires and tiled college roofs towards the hazy fens. Soft sunlight glints off a distant steeple as the cheery ring of a bicycle bell rises up from the street below. I am also on the phone to my mother, who asks me for the second time what exactly it is that I am mumbling about as I repeat the words ‘fantasy’ and ‘disappointment’, and whether or not she just heard me sob. I may omit to mention to her the hangover gnawing away at my internal organs, but I cannot blame Sunday Life for all my misfortunes.

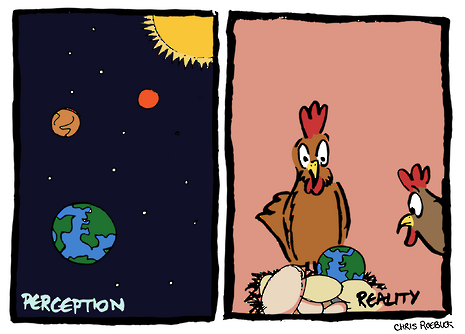

My problem is that despite the surroundings I find myself in, my second term at Cambridge has been accompanied by the realisation that the constant euphoria of my first could not be maintained. While in the rush of newness everything may live up to the archetypal Cambridge experience, we can’t fool ourselves into thinking that this fantasy will be constant, and holding on to it too tightly can actually do more harm than good. Undoubtedly, we might all get a kick out of playing up to the Cambridge stereotype (I, for one, will always remain a sucker for a gown and a bottle of port), but in the long run this is simply not a sustainable way to live. As a wise man or woman may once have said, ‘never believe your own hype’.

This is not for the reason you might expect; that if we believe our own press we’ll all morph into self-satisfied snobs, chortling all the way down King’s Parade with aforementioned bottle of port clutched confidently in hand. No, we must not believe our own hype because it creates a whole new layer of stress that Cambridge students simply don’t need. Applying to Cambridge, our parents, teachers, and friends all contribute to the expectation that it will be three blissful years of riding bicycles down sunlit cobbled streets and jolly punt trips down the Cam occasionally interrupted by the odd intellectually enriching supervision before we all merrily trot home to our castle-like abodes.

However well-intentioned these people are, and however well we may logically know that this cannot actually be the case, these collective expectations percolate through our consciousness and manifest themselves as a pressure to be having the best time of our lives all of the time in an endless utopia. In the social media age, FOMO is a universal phenomenon, but it acquires new vigour in the concentrated time-span of a Cambridge term. It’s already halfway through the academic year and, to paraphrase Heather Small, what have you done today to make you feel like a worthy Cambridge student?

Because despite many elements of fantasy, the creeping tendrils of reality are pervasive – even at Cambridge. The prettiest college chapel doesn’t stop you from getting your heart broken and the most well kept lawn will not prevent your supervisor from looking at you after a protracted pause and simply asking you ‘what went wrong’. I am sure that even punts have seen their fair share of friendships fall apart over the stress of a poorly used punting pole. Regardless of your personal position on the Whose University? or Cambridge Defend Education campaigns, it is also clear that for a significant proportion of students the ‘Cambridge experience’ far from conforms to the ideal. For those who are already finding it difficult, the message we give ourselves that we should all be constantly grateful and be ‘getting the most out of it’ can carry the implication that if we don’t fulfil this we are somehow ourselves personally at fault.

Conversely, I also don’t want to live out the rest of my time here in disillusionment and disenchantment. Admitting to ourselves that Cambridge isn’t always a paradise shouldn’t be tantamount to condemning it as a hellhole, and if we really want to ‘get the most out of our time here’ we need to escape this false dichotomy. Trying to force ourselves to experience this place in the very narrow framework of what we think it ought to be like takes up too much energy. The more that we can let go of this burden, the more we can open ourselves up. Then, we’re much better able to create a ‘Cambridge experience’ that means all the more to us for being relevant to our own unique and individual needs and predilections rather than some cookie-cutter model. And, as I think we can all feel my idealism creeping tenaciously back in here, when problems and issues do arise, as they will, we’re in a much better place to deal with them effectively when we face them head on, instead of bemoaning our inability to make our lives attain some mythical ideal.

This morning, looking out across the Cambridge rooftops the sky is grey rather than brilliant blue, and it is the hiss of a lorry’s brakes rising up from Trumpington street that reaches my ears. I know that I don’t live in an earthly paradise, and as it happens I’m fine with that.

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025

News / Caius mourns its tree-mendous loss23 December 2025 Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025

Comment / Yes, I’m brown – but I have more important things to say22 December 2025 News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025

News / Clare Hall spent over £500k opposing busway 24 December 2025 Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025

Interviews / Politics, your own way: Tilly Middlehurst on speaking out21 December 2025 News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025

News / King appoints Peterhouse chaplain to Westminster Abbey22 December 2025