This house believes gap years are a waste of time

A cultural learning curve or a preserve of the elite?

AYE: Martha Saunders

“The world is a book and those who do not travel read only one page.” These words were ubiquitous during my gap year. Whether superimposed over hyper-filtered Instagrams of turquoise South Pacific oceans or the skyline of a distant metropolis, one by one people from the Cotswold town where I grew up jetted off, accompanied by this self important fanfare, off to unlock another chapter.

Back at home, in the inner city supermarket where I worked, my 20 year old co-worker came in one day beaming and excited. He’d just got his first passport. We spent the shift pondering where his first trip abroad would be. It was going to be next weekend, a spontaneous getaway.

Next weekend he came in sour faced. The trip would be postponed until the weekend after. Then the weekend after that. Summer came, and every weekend he became a little quieter. At the end of the summer he went to the carnival in Leeds. It was his first time going anywhere outside our small town except for his birthplace, an hour or so north.

This is not unusual. He is one of Britain’s 1 in 5 people who have never been abroad and 1 in 10 children who have never set foot on a British beach. Despite the fact that this divide is almost entirely based on financial class – with more people unemployed, balancing multiple jobs, claiming benefits to top up insubstantial incomes – we consider their perspective limited, their backgrounds cultureless. But does travel really teach us that much, or is this part of a desperate and pervasive effort to intellectualize what is arguably the final stigma-free hedonism of the 21st-century privileged?

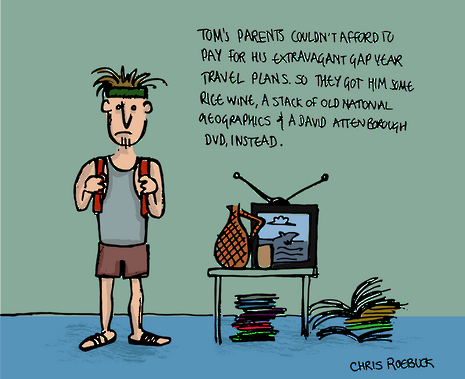

This dichotomy is never more apparent than in gap years. One by one we are packed off to Thailand and Australia and Ecuador and India. There’s no problem with this per se – travelling is fun, especially as a treat after the hard slog of A Levels. The difficulty is not that people are choosing to travel, but the self-justifying rhetoric surrounding it. In a society strangely obsessed with denying privilege, people seem to find it insufficient to admit they’re doing something because they want to. Instead the experience of travel becomes sheathed in an almost mystical quality, dressed up as an incomparable life experience, a learning curve which cannot be accessed by staying in your birthplace. This results in a strange form of snobbery that unfairly demeans the choices of the huge amount of people who simply can’t afford to “experience life.”

What do we learn from a gap year travelling that is so impossible to learn here? From the number of Facebook friends who’ve done it, a top result seems to be “understanding other cultures.” We live in one of the most diverse countries in Europe, arguably in the world. Walking down one of my local streets is like a gap year travel itinerary in itself in language, culture and cuisine; restaurants and minimarts from Poland, Turkey, Jamaica, Pakistan, Thailand, Nigeria, Romania, Hungary, India, Russia, China, not to mention the beautiful spiral minarets and domes of the mosques which fill the streets at call to prayer with their hauntingly beautiful song. For centuries, people have been carving their own little slices into our cities to fill with their culture, cuisine, and customs. People who are widely disapproved of, feared, distrusted, mocked and ignored by the very demographic who place such a great deal of value upon flying hundreds of miles to “discover” their cultures. We want a voyeuristic glimpse into a way of life we still view as exotic in countries we think are beautiful. If we wanted to discover culture, we wouldn’t need a £2k flight – we’d need to spare a few minutes to chat with our neighbours and an evening a week at a language class at the local community centre.

As for learning life skills, this is even more of a mystery to me. I spent the first month of my gap year interrailing. Here is what I learned – people in Bosnia and Herzegovina laugh at you if you use large notes. How to say “This is not my baby, I do not know this woman!” in Polish. An extensive assessment of the discrepancy in kebab quality between Kreuzberg and Istanbul. Auschwitz hurt and made my legs feel heavy and the momentousness of the bridge in Sarajevo where Franz Ferdinand was shot was sobering. But they didn’t teach me anything. What I did learn in my gap year was how to balance two jobs, budget, learn independently and deal with problematic co-workers and managers. Those are life skills. Being able to carve a didgeridoo is not.

This all comes from a problematic perception of what it is to be cultured. Being cultured is nebulous, but associated consistently with things that are exclusive and based on circumstantial fortune rather than personal choices; a good education, skills such as languages, the money to travel. Our perception of culture is rooted in an almost colonial mentality of the white savior. Our perception of the cultured is rooted in a classist assumption of expendable wealth. Go travelling by all means; it’s fun. But when discussing it, try not to think of your own somewhat inaccessible experiences as evidence that you’re independent, go-getting, open-minded. Instead, think “God, how lucky I am.”

NAY: Morwenna Jones

In my three years at Cambridge, I’ve clashed with my DoS about many things, from T.S Eliot to Matthew Arnold, but there are two things on which we are both in agreement. The first is that coffee should always be drunk black and strong enough to kill a horse and that it’s totally okay to think significantly less of someone for taking milk, let alone sugar. The second is that, regardless of what you study, what your background is or what you intend to do, taking a gap year is a very, very good idea.

I didn’t take a gap year. I applied to university the year before the fees increased to £9,000, so I faced a choice. I could miss out on a year that, heaven forbid, I’d spend actually enjoying myself and relaxing after slaving away on GCSEs and A-levels for four years. Or, I could keep my part-time summer job, save up enough money and go ‘travelling’ (or more likely do a ski season) and come back, most probably penniless and pay three times more for university.

I chose the former. It was one of the worst decisions I’ve ever made. To an even greater degree than most people, I spent most of my first year at Cambridge striking an awkward balance between making a complete tit of myself and dealing with my own immaturity. After a sheltered upbringing, I floundered in a world where, for the first time in my life, I was on my own. I’d never had to structure my own timetable before, I’d never been in an environment in which I was allowed to go out until 3am before working at 9am the next day, and I’d never had to look after myself. Lost in this strange world, the mental health problems I’d fought for two years worsened, and at the start of Lent term in my second year I intermitted.

My intermission year certainly wasn’t the gap year I’d dreamt of, not least because of the circumstances that forced me into it. But, once I got back on my feet, got a job in a coffee shop and started to grow up, I began to learn the same lessons most ‘gappies’ learn during their years out. I met people who hadn’t been given the advantages I’d had, people who’d decided that university life wasn’t for them and people who didn’t give a damn that I’d dropped out of Cambridge, and were only concerned about me not ruining their morning latte. Then, I went and spent a month working in the French Alps, blissfully ignorant of reading lists, lecture notes and supervision schedules. I learnt new things and I remembered old things that had got lost in my brain amidst a sea of notes on everything from GCSE photosynthesis to Julian of Norwich. More importantly, however, this was an environment where making a mistake didn’t impact on my time at university, or my degree at the end of it.

Admittedly, not everyone needs to take a year out to acquire the basic skills of being an adult or to recall how to have a good time. Most people manage just fine during their first year. But it still seems ridiculous that, in a world where those of us born in 1993 are going to have to wait until 2061 to retire with a state pension, we are so keen to race through the arbitrary hoops of the new modern rites of passage; finishing school, starting university, graduating and getting a ‘grown up’ job, without considering what we really want.

Some of us can very fortunately go from GCSEs to A-level and through the years of our degree, safe in the knowledge that, during the lengthy holidays, we can afford to go travelling, see the world, or secure our dream internship thanks to the wonderful system of nepotism. Some of us work hard, know how to use a calculator, perform well at interview and earn a place on a prestigious internship scheme. Some of us can’t do either of those things (after all, not everybody wants to be a management consultant) and will spend the whole summer desperately slaving away in some part-time job in the hope that, at the end of it, they might have enough to pay for half an inter-railing ticket. And this is where a gap year comes in. Unless they’re lucky enough to secure a bursary or a place on one of the university’s highly competitive subsidised travel schemes, the holidays simply aren’t long enough for some students to save enough money to go save orang-utans in Indonesia. They’re simply not long enough for some students to save up to climb Kilimanjaro and they’re simply not long enough for some students to save enough to fund themselves for the duration of the scarcely-paid city internship they’ve always dreamed of. A year, on the other hand, is.

But what if you couldn’t care less about orang-utans? What if you already know what you want to do and you can’t wait to take one step closer to the future you’ve always dreamed of? What if you’re worried that over the course of a year your fragile brain will forget all those precious gems of information it so eagerly acquired? At the end of last term, my DoS and I mulled this issue over in his cosy office where he first interviewed me in 2010. Now on a sabbatical, the academic equivalent of a gap year (only he’s writing a book, not saving orang-utans), he told me that if he met an applicant who’d spent, or who intended to spend, a year exploring their chosen path of academia, whether by reading voraciously or working in their chosen field, he’d offer them a place instinctively.

A gap year is a twelve-month opportunity to do what you really want to do and what you need to do. You can travel, you can work, you can save, you can grow, you can learn or you can simply do whatever you enjoy most. Given that opportunity, it seems obvious that the seventeen year olds asked to make a choice shouldn’t be saying ‘Gap Yah’, they should be saying, ‘Gap hell yeah!’

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025

News / Eight Cambridge researchers awarded €17m in ERC research grants27 December 2025 News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025

News / Downing investigates ‘mysterious’ underground burial vault 29 December 2025 Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025

Lifestyle / Ask Auntie Alice29 December 2025 Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025

Sport / Hard work, heartbreak and hope: international gymnast Maddie Marshall’s journey 29 December 2025 Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025

Interviews / Meet Juan Michel, Cambridge’s multilingual musician29 December 2025