What is the power of protest?

Do we let idealised images of protest obscure its many forms – and its many successes?

I won’t lie. When I say the word 'protest', there is a little image in my mind that crops up. That image portrays privileged students in ragged but expensive clothing and rainbow-coloured hair throwing red paint on, well, everything, screaming 'Fur is murder!' I personally don’t wear or condone the use of fur for the sake of fashion, but there’s something about that image that makes my eyes roll eternally.

I don’t think it’s just me, either. There’s a significant chunk of society that doesn't take those students too seriously. To say that such outlandish style of protest is obsolete in expediting social change would mean that it was once effective. But my hunch is that this was never the case. Here, however, is my other hunch.

Perhaps I’m stating the obvious, but protest, I think, manifests itself in many forms. Protest is a free education demonstration that passes Parliament Square. Protest is writing a formal letter of complaint to the Vice Chancellor. Protest is having the guts to tell your friend she or he is perpetuating misogynistic culture by referring to women as 'birds'. Protest is anything that challenges the status quo.

Even given these qualifications, I’m unsure whether they explain the stigma concerning protest. A friend recently told me that it’s because protest consistently comes from a place of anger – protest in all its forms, he said, is an angry enterprise. I’m not convinced. A letter to the Vice Chancellor, after all, seems like a pretty composed way to go about voicing frustrations. But my friend did have a point: protest is inherently antagonistic towards the institutions it seeks to change. I do not think, however, this has to be a bad thing. Getting our institutions to recognize ethical misconduct can only strengthen the integrity upon which they claim so vehemently to advocate.

Maybe, then, the stigma is present for ethical reasons. Protest is all well and good until it gets violent or disrespectful, which often it does – hence the stigma. But I confess: I've presented a distorted picture of protest. Because recently it occurred to me that there isn't just a stigma attached to protest, but a romantic notion too. A classic example of this is Dr Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’ speech – written with an acute awareness of himself as a historical actor, embedded with florid and romantic language – is now seen as a pivotal moment for the civil rights movement. Yet during a recent seminar, I discovered that Dr King had to be convinced not to use guns at the start of the movement. There’s something jarring about that. I don’t want to accept it. I think this is because we like to polarize rhetoric around protest. It needs to be poignant, morally significant, romantic, and if it doesn't meet such criteria, then comes the eye-rolling.

My point here is clearly not to berate Dr King, but rather to illustrate that we like to present events as simpler than they are – to put them in to a narrative we can make sense of. So when we see something as underwhelming as a band of hipsters protesting, albeit passionately, about the sale of fur, then perhaps we roll our eyes because we want something more romantic, or rather, something worth writing about in the history books one day.

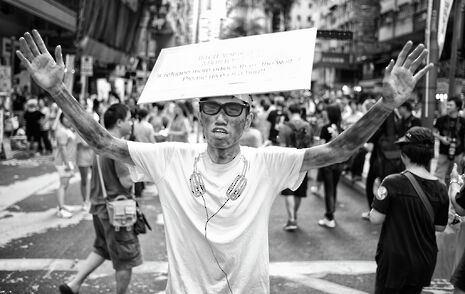

At the beginning of Michaelmas, I went to see the Israeli Ambassador speak at the Union. The building itself was guarded and fenced on that day for what they dubbed 'security reasons'. I wondered what those reasons were as I walked cautiously onto the premises, and then it became clear. Pro-Palestine supporters were protesting vigorously, banging drums and whatever they could, really, shouting “Free Palestine!” and “War crimes!” without fail for the next hour. It’s difficult to articulate what I felt while I passed the protesters and slid into the debate chamber, but whatever it was, I was in emotional overdrive. I felt something. And I think it was because it fit in so well with one of the most contested international narratives of the last century. Whether misplaced or not, I felt a sense of solidarity for the Palestinians.

But here’s the kicker: when the talk was over, friends and I ventured out to speak with the protesters, more specifically about why they didn't voice their views at the talk. Why they chose this specific way to send their message. The responses were disparate. Some wanted simply to vent their frustrations at the international community, while others truly believed their presence would mark a socio-political change of some sort. My point is that the protesters were not unified. They did not all know each other. There was no one reason that brought them all together and there was no real collective narrative that accommodated them all. To assume that they were one unified and organized entity driven by the same moral imperatives was my mistake.

This, I believe, is testament to the fact that we like to see things through a polarising lens – one that consistently places events into black and white narratives; treating protesters as one homogeneous mass of personified anger and oversimplifying the socio-political issues they attempt to flag up. I'm unsure whether we can ever let go of such filtering processes. After all, that would be like asking us to stop looking for narrative meaning in history. But perhaps we can give the concept a little slack and look beyond the imagery of hysterical students looking for an axe to grind.

Editorial: The occasional power of protest

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025

News / SU reluctantly registers controversial women’s soc18 December 2025 Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025

Features / Should I stay or should I go? Cambridge students and alumni reflect on how their memories stay with them15 December 2025 News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025

News / Dons warn PM about Vet School closure16 December 2025 News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025

News / Cambridge study finds students learn better with notes than AI13 December 2025 News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025

News / Uni registers controversial new women’s society28 November 2025